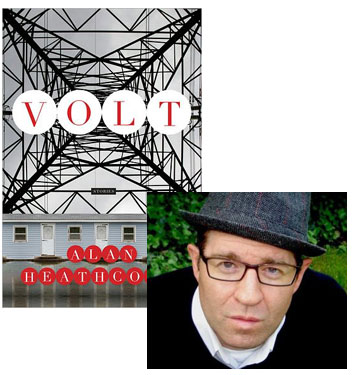

Alan Heathcock, Carried Off “Upon the Sweeping Flood”

The stories in Alan Heathcock‘s debut collection, Volt, are compellingly stark: Unable to deal with the emotions churned up by the accidental death of his son, a man simply wanders off, until he winds up in a new community where he earns money withstanding other people’s physical assaults; a sheriff goes to extraordinary lengths to preserve the tranquility of her community, and then a flood forces her to revisit her actions. The violence in Heathcock’s stories takes on a surreal quality, and yet for all its unworldliness it doesn’t lose its visceral immediacy. In this guest essay, he explains how he’s been inspired by a master of such tales.

I must steel myself. Must be brave. I must not look away. It’s hard and self-conscious and everything in me tells me I’ve gone too far. What will they think of me? What will they think if they know my mind? This is my dilemma, being a writer. I’m a naturally private man, yet the written word eventually becomes very public, judged, interpreted, and for that I try to be brave, to not falter.

I need help. When I am at my weakest I read the work of authors who’ve gone far beyond me, ahead of me, who are revered. In this regard, Joyce Carol Oates is the bravest of writers, one of the fiercest champions of unflinching truth I know.

I own an old ragged paperback of the story collection Upon the Sweeping Flood. The pages are yellow and brittle. On the first page, before any of the stories, is a quote from Oates: “I am concerned with only one thing, the moral and social conditions of my generation.” Just like that. So easy, so focused. My problem is clear. I am distracted, focusing on many things, while her concern is distilled into a single sentence. And oh how she pays out that focus.

The first time I read the title story, I was sitting in a condo on the fifth floor of a building in Chicago, Illinois. I remember it was fall, probably October, and I put the book down, trembling a bit, and stared for a long time into the golden tops of the locust trees outside my window. I was a budding writer then, and remember reflecting on my own work and thinking something like, “You’re not even close. Not even in the ballpark yet.”

The story, about a man named Stuart who, coming from his father’s funeral, on the way home to his wife and daughters, and despite the warnings of a state trooper, drives headlong into a storm. He comes upon a boy and a girl scrambling onto the road as a hurricane engulfs their land. Stuart, in his attempt to save someone, himself maybe, becomes trapped, too. The boy and girl are depicted as vulgar, desperate creatures. “The girl lunged forward and tried to push her way into the car; Stuart had to hold her back. ‘Let me in,’ cried the girl savagely.” “The thought crossed Stuart’s mind that the [boy] was insane.” “Stuart’s revulsion surprised him; he had not supposed there was room in his stunned mind for emotion of this sort.”

The hurricane gains strength, and they retreat into the house. The kids are alone, the father off on a bender in town. As the old house begins to crumble around them, torn apart by the storm, Stuart crumbles, too, his humanity peeled away like paint from an old clapboard. In the onslaught he loses himself, becomes a personification of the storm’s brutality, that storm that lives in the impoverished human condition and shows itself when pressed into survival.

I won’t spoil the ending other than to say it’s one of the most startling I’ve ever read. In the final lines, Stuart madly waves his hands at a distant boat, crying out, “Save me! Save me!”

That pretty much sums up how I felt, too. I’ve reread this story a dozen times or so, and it never loses its truth or potency. I read it after watching images from Hurricane Katrina, again after the tsunami in Japan, people trapped on roofs, people looting in the streets, living in the pain and squalor left in a storm’s wake. How did Joyce Carol Oates know this would happen? Shouldn’t we have known? “Save me! Save me!” she wrote, as if from the future, knowing our fate well in advance.

“Upon the Sweeping Flood,” is hands down the most beautiful and brutal story I’ve ever read. It steels me, gives me permission to look directly at the thing and to not flinch. Because in the brutal truth there is also beauty: for us to be saved, we must first see ourselves imperiled.

I will steel myself. I will be brave. I will not look away.

13 April 2011 | selling shorts |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.