Overwhelming Fear with Acceptance

Recently, someone steered me toward a GQ profile of golf coach George Gankas:

Gankas’s great flaw as a player, in retrospect, was fear. Now he teaches his students to overwhelm fear with acceptance. Stay present, he says. When you’re out on the golf course, don’t get too sunk into yourself; look up from the ball, at the beauty of the natural world, and get outside your own traitorous body, your own monstrous ego.

“For me, to always look up and out is huge because I can see detail in the trees,†Gankas told me. “It gets me present. It gets me out of my head.†He said that lately his eyesight, which had been excellent, had begun to fail him. “I need to get my eyes fixed so I can get back to that. Because if I’m in my head, I’m miserable. I’m running through thoughts. And a lot of times, that’s not where I want to be. So I teach my players to stay present. And if I’m not doing it myself, I’m not going to teach them to do it.â€

That sounds familiar to me, even though it’s been about thirty years since I last went out on a golf course (in part because I was never particularly very good at it). I think a lot of us have probably experienced something similar in our writing practices—those days when we spend so much time wrestling with our anxieties and fears that we’re unable to focus clearly on the story.

We find our way out of that dilemma following much the same path Gankas recommends to his students—by setting ourselves aside, and paying attention to the moment in the story that’s before us. (Or it could be a poetic image! I just happen to have a mental bias toward narrative.) Stop worrying about your ability or inability to put that moment into words; just be with it for a while. As you do, you’ll begin to understand what needs to be said in order to describe that moment, and you will write. You may not find the exact right words the first time, but don’t worry. You can figure that out later, if you need to. (If you do get it right the first time, way to go!)

Of course you haven’t really taken your mind out of the picture entirely. You’re still there, picking and choosing your moments, picking and choosing the words to describe those moments. You’re not just channeling raw unfiltered prose from some extra-dimensional literary realm—and if you’re like me, you’re very conscious about all that, pausing, reviewing, and revising as you go along, even in the “first†draft, long before another set of eyes takes it in.

The trick is, though, that I’m not questioning whether I can do it, no matter how long it takes me to figure out how to do it. (Which is not to say I couldn’t still screw it up, all the same! If I do, though, I’ll have to have another go at it. Maybe more.)

I recently spoke with memoirist Lara Lillibridge for a literary magazine called Hippocampus, and one of the things we wound up discussing was the source of this newsletter’s title. It’s the opening to one of my favorite Mekons songs, “Memphis, Egypt,†and the full line goes: “Destroy your safe and happy lives / before it is too late.â€

It’s been a song that has stuck with me for decades, and it felt really apt to use it to talk about the writing life. I mean, you don’t become a writer because you’re complacent. You become a writer because there are things picking away at you—things you have to get out. And in order to get them out, sometimes you have to blow up your routine and find a new way of doing things.

I also want to share an interview I did with Hurley Winkler for her Lonely Victories newsletter back in June! One of my favorite moments in that conversation was about that process of destroying our safe and happy lives and finding that new path. Carving time out of your schedule to focus on your writing is important, but there’s more to a writing practice than just picking up the pen or sitting in front of the keyboard.

I believe that, to the extent possible, when life presents us with options, it’s desirable to make choices that nourish our writing practices—not all of which involve the act of writing. That’s important, obviously, but it’s also important to cultivate inspiration and practice empathy and compassion. All three of those will lead to better writing down the line.

When you’re able to approach your story with empathy and compassion, when you’re able to take inspiration from the example set by others… these are all good ways of setting yourself aside and accepting the task that awaits you.

This post was first published in “Destroy Your Safe and Happy Lives,†a newsletter I’ve been writing since 2018. If you’d like to subscribe and get every new installment delivered to your email (free!), you can do that here.

12 August 2021 | newsletter |

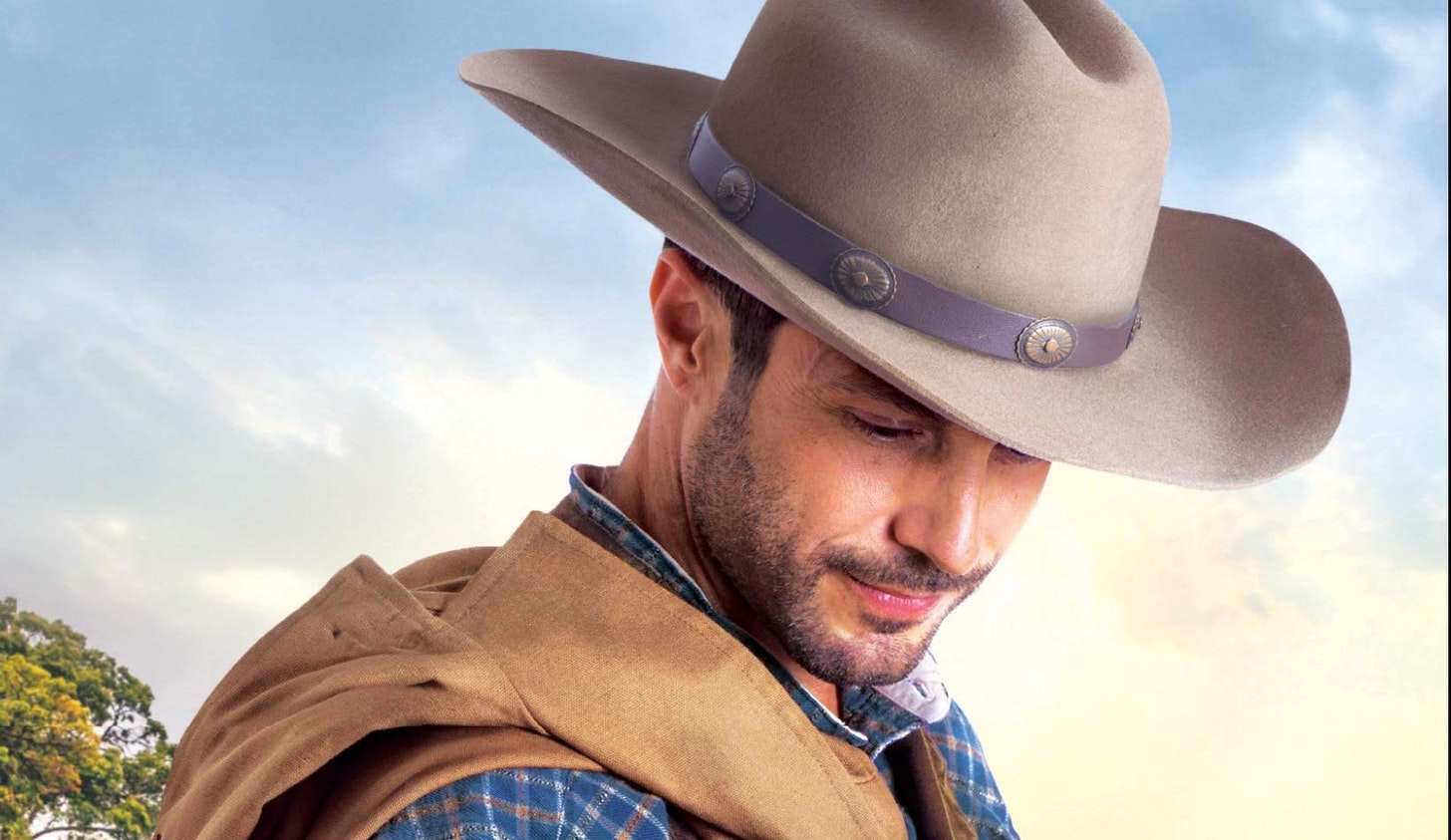

I Have a Great Many Thoughts About At Love’s Command

When the Romance Writers of America presented an award for “Best Romance with Religious or Spiritual Elements†to Karen Witemeyer for her novel At Love’s Command, several of the genre’s fans (including a number of writers) were extremely pissed at this decision, arguing that a former officer in the United States cavalry who had participated in the massacre at Wounded Knee, even a fictional one, should not be held up as a hero in a historical romance novel.

That sounded reasonable to me on general principle, but as I noted on Twitter, it was entirely possible the hero had engaged in a searing moral self-examination and was committed to a lifetime path of repentance and reparation. Or Wounded Knee could just be a colorful bit of backstory in an otherwise generic romance. I didn’t know, and I would have to read the book to find out.

Luckily, my public library had the ebook, so I downloaded it and got to reading. (Before that, though, I learned a lot about what was at stake by reading tweets from romance writers like Jackie Barbosa, Eve Pendle, Clyve Rose, and Courtney Milan, among others.)

Meanwhile, the RWA’s president had issued a statement declaring that At Love’s Command met all the requirements of an inspirational romance, particularly a narrative arc of personal redemption by means of a religious awakening, and the judges hadn’t noticed anything wrong with Karen Witemeyer’s depiction of Wounded Knee, so if the judges thought it was the best book in its category, then it was the best book in its category, no matter how many people didn’t like it.

This did precisely nothing to abate the criticism, and the RWA’s board ended up scrambling into an emergency meeting, where they decided that they suddenly had the power to overrule the judges and rescind an award days after it had been issued, so they were going to go ahead and do that.

I was just about done reading the book at this point, and I was convinced that the fans protesting the award were spot on: Witemeyer’s novel does not work as a redemption narrative, not least of all because her hero, Matt Hanger, doesn’t regret the genocidal campaign that led to Wounded Knee. He only regrets that Wounded Knee went badly. “This was supposed to be a simple weapon confiscation,†he thinks. “An escort to the reservation.†That’s his idea of “bring[ing] justice and order to the frontier.†Wounded Knee was a legitimate conflict, in his mind, until Lakota women and children were killed, because that offended his sense of honor. Witemeyer even has him literally assert “plenty of blame and plenty of sin on both sides†of the conflict between the United States and the Native population (emphasis mine), specifically blaming agitators among the Lakota for the way Wounded Knee got out of hand.

Anyway, after Wounded Knee, Matt and three of his comrades â€[had] all sworn an oath to do everything in their power to preserve life and justice.†They are not, however, atoning for the White supremacy of the Indian Wars. Instead, they’re “fighting the battles ordinary people couldn’t fight for themselves… protecting the innocent and righting wrongs.†Yes, they’re mercenaries, but they charge fair rates, and they always fight for the little guy.

If this sounds like The A-Team to you, it’s not an accident. One of the four ex-soldiers is even Black. (Never mind how Witemeyer makes that work in 1890s Texas; that would be a whole other essay unto itself.)

On her website, Witemeyer discusses how Hanger’s Horsemen, the main characters in At Love’s Command and its sequels, were inspired by The A-Team. (She’s less candid about the setup being a variation on a specific episode.) Ultimately, though, using the A-Team as her inspiration is precisely why the “redemption†narrative fails.

The A-Team, after all, didn’t become the A-Team to atone for anything they did in Vietnam. (If I remember correctly, the show consistently and explicitly avoided criticizing the war.) They became vigilantes for the common man because it was the only job open to four fugitives with their combat skills. So the pretense that four ex-cavalrymen spend their days riding around Texas, defending small ranchers and the like, because they feel guilty about taking part in a genocidal battle, is flimsy as hell.

I want to share something with you that Bethany House, the publisher of At Love’s Command, wrote in defense of the novel before it was rescinded, when it was still just a matter of intense vocal criticism:

“In the opening scene of the novel, Witemeyer’s hero, a military officer, is at war with the Lakota, weary of war, but fully participating in the battle at Wounded Knee. The death toll, including noncombatant Lakota women and children, sickens him, and he identifies it as the massacre it is and begs God for forgiveness for what he’s done. The author makes it clear throughout the book that the protagonist deeply regrets his actions and spends the rest of his life trying to atone for the wrong that he did.â€

The idea that Matt “begs God for forgiveness for what he’s done†takes up literally one sentence in the prologue: “‘God forgive us,’ he murmured.†That’s the full extent of his “repentance.†He doesn’t absolve himself for (what he thinks he did wrong at) Wounded Knee; he still sees himself “a man who carried demons in his saddlebags.“ But because he’s chosen to, basically, let go and let God, the novel considers him redeemed—and readers are expected to follow suit.

As for the notion that Matt “spends the rest of his life trying to atone for the wrong that he did,†he does nothing in the book to address his sins against the Lakota at Wounded Knee. Instead, he assuages his guilt as a hired gun for White folks in peril.

Here’s where we’re going to get theological for a bit, because this is a cheap form of repentance that’s all too common in inspirational romance, because it’s all too common in modern American Christianity—the idea God gives us infinite resets if we just say we’re sorry. (It’s a lazy interpretation of 1 John 1:9: “If we confess our sins, he is faithful and just and will forgive us our sins and purify us from all unrighteousness.â€)

John the Baptist, though, calls on us to “produce fruit in keeping with repentance.†(Matthew 3:8) That means saying you’re sorry isn’t enough—you must change your life, and the way you live your life, to set the balance right. Maybe you could get away with citing James 1:27 and arguing that Matt and his comrades are “looking after orphans and widows in their distress,†but they’re not doing anything to make up for the deadly harm perpetrated on the Lakota. They don’t atone for that.

The need for specificity in atonement is made abundantly clear in Leviticus. If you sin against your neighbor, you must make restitution in full, and then some, to your victim. (6:1-5) Ezekiel, too, is clear about the requirements for redemption (33:15): You need to restore what you broke, reimburse what you stole, and then “walk in the statutes of life, not doing injustice.â€

If At Love’s Command were a novel about a cavalryman so appalled by his conduct at Wounded Knee he dedicated his life to protecting the Lakota and making reparations, it would be a redemption story. But that’s not the book Karen Witemeyer wrote.

Let me be clear: There is no redemption in At Love’s Command, because Witemeyer refuses to confront the reality of why Wounded Knee happened, so Matt and his colleagues aren’t atoning for the real damage they did there. They’re merely play acting at repentance. He’s not a saved man; he’s just a vigilante with a Scripture-inflected sense of honor and a dark past.

That’s a distillation of a few Twitter threads I’ve written about At Love’s Command over the last two days. It’s a story that interests me because it’s not the first time the Romance Writers of America have blundered into a minefield of their own White privilege, and because I’m a fan of the genre with a particular interest in inclusive stories that share diverse experiences with readers.

I want to shift gears, though, and talk about this story in the context of a theme that I’ve hit upon in this newsletter over and over again: We take up our writing practices because we want to find out what matters most to us, because we have something to share with the world and in order to share it effectively, we need to understand it. It needs to be clear to us before we can make it clear to anyone else.

If we write to share our truth, you might well ask me: Okay, Ron, what if At Love’s Command is Karen Witemeyer’s truth? Shouldn’t we honor that?

That’s a tough one to answer in some ways, especially since—as a matter of strictly technical, literary achievement—At Love’s Command struck me as fairly typical of its subcategory, and if I didn’t have this strong moral objection to its content, I might readily conclude that it was probably as deserving as any of the other finalists for the prize it (temporarily) won.

The thing is, though, that neither “her truth†nor “your truth†nor “my truth†is necessarily the truth. I can recognize Karen Witemeyer as somebody who’s trying to articulate her views on our relationship with God, somebody who’s drawing upon the history of the United States and modern pop culture to make a case for how we should live in relation to God and to one another. At the same time, once she’s made her case, anybody who sees significant flaws in it should be able to discuss those openly, to say this is where she got it wrong, this is what she’s overlooking.

I don’t fully know what’s in Karen Witemeyer’s heart. I don’t think that she’s completely unconcerned about the genocidal brutality at Wounded Knee—at the very least, she seems to think it was awful enough that it would make a decent man who took part in it feel guilty about what he did. That, however, is the problem: The novel shows infinitely more concern with how Matt’s role in Wounded Knee makes him feel than it does with the pain inflicted on the Lakota. They’re whisked off the stage as soon as the battle is over; Matt might think now and then about how awful it was, but we never see how the Lakota struggle in the aftermath of his actions, because Witemeyer makes the authorial choice to never confront that aftermath directly.

As such, the pain of the Lakota—a very real, very visceral historical pain—is effectively reduced to a convenient hook for a story. It’s not just disrespectful, it’s unnecessary. As I learned when I was looking up some of the historical context, Matt and his comrades could just as easily have served in the Johnson County War, a conflict between struggling settlers and wealthy cattle ranchers in Wyoming, just a few years after Wounded Knee. Heck, that setting actually suits her A-Team-inspired “vigilantes for the common man†theme better than Wounded Knee, and would make their willingness to fight for the economically disadvantaged more narratively coherent.

But, I suspect, it might be more “dramatic†for Matt to be haunted by the atrocities of Wounded Knee than disillusioned by the brutal class warfare of Johnson County. The more conspicuous the sin, after all, the more striking the apology. Or it may simply be that Wounded Knee was low-hanging narrative fruit. Again, I can only speculate.

Alongside my speculation, though, I can offer an observation: When you use the pain and trauma of a marginalized community as colorful shading for your protagonist’s past, when you treat other characters as props in his emotional journey, that’s neither empathy nor compassion. Matt’s expressions of guilt and remorse may give him the illusion of emotional complexity, but they do nothing to address the pain they invoke.

As good as At Love’s Command is from a superficial standpoint, I believe it falls short as an emotional and a moral document. It may well be the clearest expression of what weighs most heavily on Karen Witemeyer’s heart that she could create at the time of writing—and, again, it doesn’t hurt to be mindful of the fact that she made an effort. In attempting to write about how a man lives with sins that seem unforgiveable, however, I wish that she had been willing or able to give her attention to the Lakota, the victims whose forgiveness Matt needs the most to secure in order to demonstrate… well, not that he’s worthy of God’s forgiveness, because we’re all worthy of God’s forgiveness.

God, I believe, is patient with us, and doesn’t want us to perish (2 Peter 3:9). At the same time, though, God is waiting for us to show that we understand that everyone else is as worthy of God’s love as we are. That’s why Matt needs the Lakota’s forgiveness; that’s why he needs to make amends.

That’s the kind of story I would like to see. An even better story would be one that didn’t just acknowledge the Lakota perspective, but centered it, shunting the repentant White character off to the margins. Maybe somebody is working a story like that. Maybe it’s you. If it is, I hope you keep at it. I’m sure I’m not the only one waiting to read it.

This post was first published in “Destroy Your Safe and Happy Lives,†a newsletter I’ve been writing since 2018. If you’d like to subscribe and get every new installment delivered to your email (free!), you can do that here.

5 August 2021 | newsletter |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.