May-Brit Akerholt: “Bless thee, Bottom! bless thee! thou art translated!”

photo courtesy May-Brit Akerholt

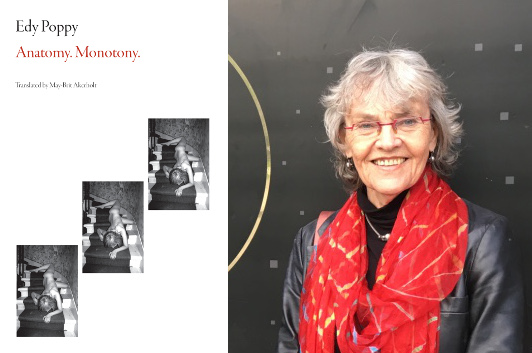

A few weeks ago, I was invited to attend a reception at the Norwegian consulate, where I got to meet the novelist Edy Poppy, who was celebrating her American publishing debut with the Dalkey Archive Press’s English-language version of her first novel, Anatomy. Montony. which Siri Hustvedt—who was also there to engage Poppy in an informal public dialogue—calls “a devilish hybrid: part autofiction, part literary, cinematic, and musical dance of allusions, and part chronicle of the mute body’s aches and pains and lusts and needs.”

Poppy was in the city for a few days after the reception, so after reading the novel over the weekend I met up with her in a coffee shop in Brooklyn to chat for a bit. As a story, Anatomy. Monotony. reminds me of films like Jean-Luc Godard’s Contempt or Lars von Trier’s Breaking the Waves, stories about couples who poke at their marriage with a sharp stick with devastating consequences, so we talked about that for a bit, and about how, more than a decade after the book came out in Norway, she’s still called upon by the media to talk about unconventional relationships—which, she says, she doesn’t mind at all, and I totally get that. Who wouldn’t want to write a book that held people’s attention so strongly they were still asking you about it years later? I also reached out to Poppy’s translator, May-Brit Akerholt, who was glad to share some thoughts on how she rendered Poppy’s very interior (and allusive) Norwegian into English.

Bottom’s transformation into an ass in Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream is no more remarkable than that of a play, a novel, a poem into another language. Both appear in a foreign dress, both look somewhat alien to their old friends, and both speak a language that seems both recognizable and unfamiliar. Snout, who initially flees in mortal fear, soon comes back and says: “O Bottom, thou art changed! What do I see on thee?” On thee? Snout realises that the spirit and heart of Bottom is unchanged, it’s only his appearance that is different.

The word ‘translation’ is a mis-nomer; each new version of a work in another language is a form of interpretation and adaptation. Methodologies and theories of translation are often impractical, even irrelevant, when writing new versions of a literary work. In terms of drama, a translator works with a play’s theatrical language: its unique music, rhythm, tone, dramatic enigma; when translating a novel, you work with the unique music, rhythm, tone, the enigma at the core of the work; when translating poetry, it’s the unique music …

A translator struggles with similar problems and questions and elements across the whole spectrum of literature, only in different degrees according to the genre, and of course, to the work itself. It’s the individual voice of each writer that must form the core of any translation or adaptation. The starting point of a translator’s work must be to explore the unique voice of its creator. Otherwise how can it be possible to bring forth the idiosyncrasies of a particular work in another language?

28 June 2018 | in translation |

Lynn Sloan: Coast to Coast with Ollie

photo courtesy Lynn Sloan

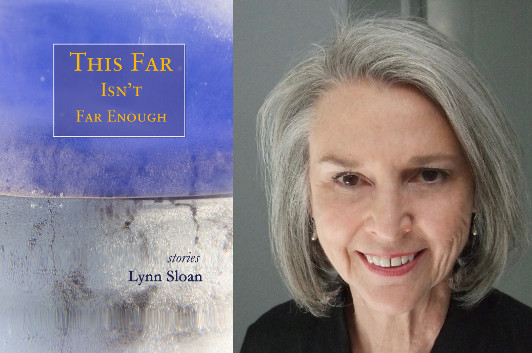

Lynn Sloan recently had a story from her debut collection, This Far Isn’t Far Enough, chosen for inclusion in the acclaimed radio series Selected Shorts. It’s a potentially huge boon for an emerging writer, and I hope it helps introduce readers not just to “Ollie’s Back,” but to other fantastic stories like “Call Back,” in which an aging actor struggles to take care of his wife as she goes through dementia, or “Nature Rules,” which starts out as a story about a woman dealing with a bear rummaging through her garbage cans but takes a sharp detour into family drama. In this guest essay, Sloan talks about what it’s like to have your work showcased in what just might be America’s most widely recognized reading series.

“VIP parking at the Getty,” my friend exclaimed.

I had just her told that a story of mine that she’d read five years ago in messy draft form had been chosen for Selected Shorts on Stage. Selected Shorts! She and I often talked about the outstanding short stories read by notable actors we’d listened to on this long-running NPR show. I thought she would be wowed by my news. My story, “Ollie’s Back,” chosen for this fabulous literary show—amazing. The program, “A Feast of Fiction,” would also include stories by Donald Barthelme, Stephen Tobolowsky, Annie Proulx, and Willa Cather (Willa Cather! I read Willa Cather in eighth grade!). Such luminaries and me—astonishing.

This Selected Shorts, which usually performs at Symphony Space in New York City, would be at the Getty Center in Los Angeles in March, which is way better than New York City in March, and I would be there. None of this impressed my friend more than the fact that I would be given a VIP pass to park at the Top of the Mountain at the Getty.

Two months later, as I stood on the plaza of the Getty an hour before the performance I understood why: VIP, Very Important Person anything, doesn’t enter the normal writer’s life. But here I was an hour before my story, “Ollie’s Back,” would to be read by the actor Nate Corddry on the plaza of one of the world’s most beautiful museums with a view that overlooked Los Angeles and reached to the Pacific Ocean. It doesn’t get better than this.

18 June 2018 | selling shorts |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.