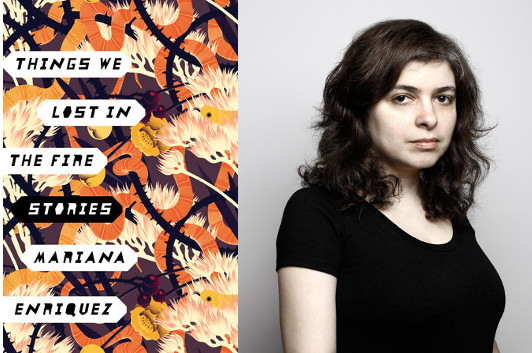

Mariana Enriquez: Robert Aickman’s Beautiful Uncertainty

photo: Nora Lezano

As you read the stories in Mariana Enriquez’s Things We Lost in the Fire, you’ll start to feel an unnerving sensation at the back of your mind, sometimes poking its way to the surface. Stories like “The Dirty Kid” or “The Intoxicated Years” aren’t horror; they aren’t even particularly supernatural. But they’ll unsettle you just the same. They’re… eerie. I understand that feeling a bit more now that I’ve read this guest post, where Enriquez talks about reading anthologies with writers like Shirley Jackson and Harlan Ellison…and another author I’d not heard of before, but whose stories sound intriguing enough that I want to track him down now.

Short stories weren’t my first love: When I started to write, the novel was my undertaking. I had to make my way to the short story and I managed that after fifteen years of writing. Argentinean literature is famous for its stories: its most important writer, Jorge Luis Borges, never wrote a novel and in fact never wrote a text that was too long; even his essays are short. Much of the canon—Julio Cortázar, Silvina Ocampo, Leopoldo Lugones, Horacio Quiroga, and, more recently, Abelardo Castillo, Hebe Uhart, and Fogwill—are above all short story writers, even if they occasionally dabbled into the novel. When I began, I didn’t want to go against tradition: one writes what one can. But the most natural movement for an Argentinean writer is towards the short story because that’s what he or she has read the most. Of course there are many novelists too, it’s just that the quantity and quality of short story writers is surprising for a national literature.

Nevertheless, if I have to choose a story or a writer who has influenced me, my favorite is not an Argentinean. He’s British: Robert Aickman. Reading him impressed me to commotion. I came across him in those cheap horror story anthologies that were very popular in Spain and Latin America in the 1980s, anthologies that mixed Shirley Jackson with Harlan Ellison, Henry James, Arthur Machen and had titles that scared off classy readers like Great Super Terror Vol. 1. The influence of an author who writes in a language different from your own is strange: the influence or the admiration reaches a place that is less technical and more intuitive. I suspect that the language of my stories is directly related to the tradition in my tongue. But the author who shook me to the core is Aickman.

He’s a superb creator of atmospheres. I read his stories many times to try to understand how he does it and I could list some of his decisions, but that would be unfair. Aickman eases one of my vexations with the conventional story. Particularly in genre stories, I was irritated more and more by the closed endings, the reassuring explanations. Closure: It doesn’t exist in life, I didn’t see why it had to exist in fiction. And I also didn’t want to understand step by step all the stories I read. Do we really understand everything that happens? I’d say we barely understand anything at all.

At first I also didn’t understand Aickman. I loved him, was fascinated and dreamed about his stories. But I didn’t understand them. I then realized that that was what mattered: the radical strangeness, the non-linear lines that move the stories with a very strong internal logic. I remember the suffocating atmosphere in the apartment of “Ravissante,” the terrible insomniacs roaming through the forests in “Into the Wood,” or the horrible erotic fantasy of “The Swords.” But my favorite story, the one I reread and that still startles me, is “Ringing the Changes.”

It begins with a couple on vacation during off season in an English village with a medieval centre, beside the sea. She is much younger than him. They arrive at a hostile hotel where the staff and the few guests are moody and drunk. The couple goes out for a walk, they want to find the sea: in the darkness of the beach, they smell it, they feel the salt and the wind but they don’t find it. I can’t explain why the disencounter with the sea is so unsettling but it’s terrible, distressing. On top of that, the whole time bells are ringing from a nearby church. The ringing doesn’t stop as if some mechanism had broken down and no one offered to fix it. The couple is bothered by the sound but not enough to not dine at the hotel.

The whole time, while one reads this story, you ask yourself: “Where is it taking me? What does it want? What is it about?” One of the guests, drunk but lucid, tells the couple they should leave the village, that the bells ring to wake up the dead. There begins the most frightening horror story imaginable, a mix of zombie apocalypse with a macabre dance of the Black Plague.

I don’t know what the story is about. It’s erotic. It’s about love and loneliness; it’s a story about the old and the modern that clash, of the supernatural that lays waste to the everyday. But there is something else that I’m not able to fully understand, and I appreciate that so much from Aickman because he knows, with master skill, that uncertainty—when it is not a trick—is valid, powerful, doesn’t have anything to do with the lazy open endings that make the reader work for nothing, that deceive him or her. Aickman never disappoints because he speaks of the uncertainty that corrodes us. We ignore what’s most important. We don’t know which is the word that can help knock down our fragile lives. We don’t know if love can turn into torture. We don’t know what happens after death. We surely don’t know when our end will come.

10 March 2017 | selling shorts |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.