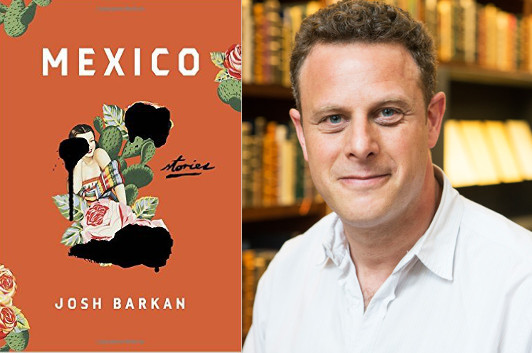

Josh Barkan: The Inner Meat of the Story

photo: Adrian Mealand

Josh Barkan likes to get inside his characters’ heads—deep inside. So while the stories in his second collection, Mexico, are full of action—a chef is forced to surprise a drug lord with a truly astounding entrée; a teacher watches as two students in one of his classes; the children of rival drug lords, enact a Romeo & Juliet-esque drama in another—they’re ultimately about the interior journeys of the narrators. That teacher, for example? He’s also spurred by what he witnesses to rebuild the sundered relationship with his Orthodox Jewish father-in-law. In another story, a woman facing a certain cancer diagnosis listens impatiently as another woman describes how she got a set of horrific scars, only realizing at the end that the story really does hold meaning for her. Here, Barkan talks about some of the inspirations he draws upon as he works his way to finding his characters’ voices.

Short stories often don’t have time for long sections of interior thought, but the traditional reliance on plot to move the short story along seems less interesting to me than finding out the way the protagonist perceives and thinks about the world. Two authors that emphasize such interior perception and thinking are Saul Bellow and Denis Johnson. Bellow rarely wrote short stories—the novel and novellas gave him much more room to follow the long thought processes of his protagonists—but in two stories, “Looking for Mr. Green” and “A Silver Dish,” he showed how great depth of internal thought can be revealed in the short form.

In “Looking for Mr. Green,” a cerebral character, who has trained as an academic, finds himself working in the Depression for a welfare office, delivering checks to the poor. His supervisor laughs at the lack of utility of the protagonist’s university training for such work. But as the protagonist walks around the city of Chicago, trying to find the elusive Mr. Green, he contemplates about what is permanent and what is impermanent, and what his relationship is to the surrounding poor neighborhood that he is experiencing for the first time. Full of self-doubt, the protagonist is finally able to find Mr. Green—or someone who he lets himself believe is Mr. Green—to give the check to, and he is able to come to the conclusion that in the end he “could” find Mr. Green, which ends up reaffirming the validity of all of his cogitating.

In “A Silver Dish,” Bellow’s protagonist faces the loss of the death of his father, and he has to determine whether his father was a crook, who used him for his own selfish ends, or whether his father was trying to liberate him from living a religious life that was not his own. The text moves in and out of the deep interior thoughts of the protagonist, as church bells toll, one week after the death of his father. Complex ideas of love, and that the world was “made for love” are reflected upon, and by the end of the story the protagonist accepts that he is both like and unlike his father in crucial ways—sharing the charisma of his father but not his father’s selfishness.

The depth of such interior thinking creates characters that grapple intellectually with their problems as they experience them. And this is precisely the kind of character that interests me—characters who not only face problems external to themselves but who must think about their predicament. The thinking is both the potential solution and the problem, itself. As Bellow points out, the mind and the body are often at odds. His characters fight within themselves.

In a related area, the subjectivity of perception interests me in many of the best stories. Denis Johnson highlights, in stories such as “Emergency,” the ways reality changes as our moods change. In “Emergency,” the protagonist takes drugs, and as he wanders from the University of Iowa hospital where he works, and then out into the cornfields of the surrounding city, to the sad fairgrounds of the county fair, and to a drive-in movie theater where the posts for car speakers look like tombstones, we see him deal with the elegiac feeling of the Vietnam War.

The story reflects the mournfulness of the character, the setting is described in such a way that it reflects the subjective perception of the protagonist. Hospital rooms seem to have blood on the floors, even when they do not. Time moves forward rapidly and then slowly. The protagonist is taught that he has been a “fuck up”—literally and symbolically, killing baby rabbits found on the road. He learns he must help others to escape the Vietnam War, such as a draftee and defector he finds hitchhiking who needs to get to Canada. The bleakness of the war is reflected in the subjective, swirling, dark perception of the protagonist.

The meat of a story comes not from the story but from the interior consciousness.

6 February 2017 | selling shorts |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.