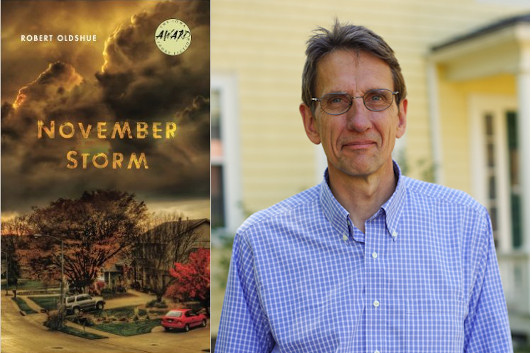

Robert Oldshue: Is There a Doctor in the House? (Can Somebody PLEASE Get Him Out of Here?)

photo: Robin Rodin

One of the earliest stories in November Storm, Robert Oldshue’s Iowa Short Fiction Award-winning debut collection, has a character who teaches eighth greade math in my old hometown in the Boston suburbs, a few years before I would’ve been taking eighth grade math. (I’m pretty sure it’s not actually based on any of my junior high math teachers, but to be honest I don’t really remember any of them that well.) But what I really love about Oldshue’s fiction is the way he uses voice to carry us through a sequence of events, whether it’s the first-person narration of domestic crises in “Home Depot” or the analytical overview a psychiatrist applies to his personal and professional life while cycling through his contemporary caseload in “Mass Mental.” That last one’s interesting because, as Oldshue notes in this guest post, despite his long career in medicine, it’s the only story in the collection about a doctor. Here’s why…

Because I’m a physician who writes fiction, I’m often asked how I do both. People want to know how I find the time, and, generally, I describe the deplorable state of my lawn, seeing patients while wearing mismatched socks and unironed shirts, and forgetting dates, including the date of one very public reading. The thing people don’t ask but should is how I shed my doctor self when I’m my fiction-writing self.

And this is what I’d say: I don’t. I can’t. Instead, I make myself aware of the differences between the two so, on a given day, I know which one I’m doing.

Difference 1: There may be more activity in an ICU than at a dinner with friends, but there isn’t, necessarily, more action. In emergencies, people retreat into familiar roles, they don’t experiment with new ones, which is fine as long as a story keeps that straight. Recycling old, recostumed selves rather than exploring new, unexpected selves is a fallacy of medical T.V. shows and why they are, as a result, not dramatic but melodramatic. Forget the ICU. Write about dinner.

Difference 2: There isn’t one medical identity, there are, for most doctors, three. Frederick Reiken, author and writing teacher at Emerson College and the Warren Wilson Low Residency MFA developed the concept of the ANC (Author, Narrator, Character) Merge. To avoid it, writers have to separate themselves (the author) from whatever persona they choose to narrate their story, both of which must be separated, in turn, from the character, even if the writer is writing memoir or the narration is first person. Doctors have a similar struggle with the PDP (Person, Doctor, Patient) Merge, and doctors who write fiction in which a doctor appears have to negotiate both merges. If you’re a doctor, writing doctor stories is harder, not easier.

Difference 3: Rosamund Lupton, a friend and the author of Sister, Afterwards, and The Sound of Silence, pointed out that the psychological novel is actually an oxymoron. When doctors diagnose, they are moving from concrete details true for one and only one patient to an abstract, reductive conclusion that results, hopefully, in the same number of milligrams of the same medicine being given had the patent presented in Omaha or Houston or Cleveland. The thought process of fiction is from the general to the specific (‘Give us more details!’ writing teachers implore), while the thought process of medicine is from the specific to the general. If medicine and writing fiction are related, it’s as opposites.

Difference 4: You can write a story about a drunk, but the story can’t be drunk. Otherwise, it suffers the same perceptual limitations as its character. My first efforts at fiction were limited, not by alcohol, but, even worse, self-importance. ‘There I was: pain to my right, death to my left, fear in front of me. What was a doctor to do?’ Doctors are central to the action in hospital stories. In literary stories, they’re furniture. Chekov wrote about people who happened to be doctors. He rarely wrote about doctoring.

A Similarity: William Osler, the father of modern medicine, said that a doctor’s job is to cure rarely, to alleviate pain sometimes, but to comfort always. Short stories and novels are much the same, at least the ones that I admire. Characters are here. Then they’re there. Like people in the real world, they change but not much. When doctors can’t help, patients want them, at least, to care, and readers want the same from their writers. Readers, like patients, want their feelings to be respected.

Another Similarity: But patients like it better when you can help, so, if you can, you should. Readers too. As Isaac Bashevis Singer said, a writer’s job is to instruct and to entertain.

So, after twenty-five years of writing fiction while practicing medicine, I published a collection of doctor stories in which, guess what? There’s no doctor, except one about a doctor who makes a mistake. My advice: the way to free your writing from whatever you do when you’re not writing is to embrace and understand rather than to deny it. Trust me. I’m a… writer.

2 January 2017 | selling shorts |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.