Lazer Lederhendler’s French-English Wall

photo courtesy Biblioasis

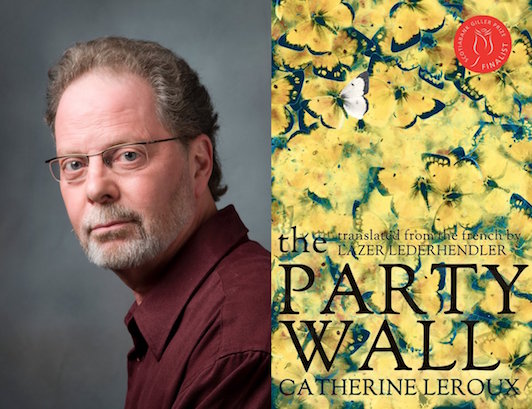

Canadian novelist Catherine Leroux’s second book, The Party Wall, won the Quebec Booksellers Prize and the Prix France Québec when it was first published in French in 2014. Lazer Lederhendler’s English-language translation, published this year by Biblioasis, has just won Canada’s Governor General’s Award for translated literature, and it made the shortlist for the Giller Prize for fiction, too. I’m pretty excited about this novel; at first, you don’t know how its various threads, from two young sisters walking through a threatening neighborhood to a Canadian prime minister in what now reads like an all-too plausible dystopian future whose wife uncovers an earth-shattering secret, connect to each other. But Leroux brings everything together in a way that still allows each story to maintain its separate power—you might spend some time trying to guess how she’ll do it, but it’s not going to distract you from the dramas she’s set up for her characters.

Leroux is just one of many Québécois writers Lederhendler has translated in recent years, making this literary scene accessible to English readers. In this guest post, though, he hits upon an idea that makes me think about just how thick (or thin!) we should make any line we draw between Québécois literature and English-language Canadian literature.

In a past life teaching English and, later on, translation in Montreal, I often made a point early in the term of quoting Wallace Stevens’s well-known aphorism, “French and English constitute a single language.” Granted, most people anywhere would find it hard to get their heads around this concept, let alone college students in Quebec, where the relationship between French and English is at the heart of a centuries-old conflict that is far from over.

My aim, though, was not to persuade students that Stevens was right but rather to bring into question some widespread and entrenched assumptions that draw a sharp, dichotomous boundary between the two languages: “English is the language of business, French the language of diplomacy”; “French is difficult, English is easy”; “English is concrete, French is abstract”; “English is demotic, French is elitist,” and such. Whereas to postulate that English and French somehow form one language is to floodlight the overlap, the liminal region where kinships and affinities as well as tensions (the dreaded “false friends” and their kind) are played out.

The Party Wall, my translation of Catherine Leroux’s novel Le Mur mitoyen, is very much concerned with the liminal, as evidenced by recurring tropes involving walls (of course), doors, horizons, borders, tectonic plates, and the like. Here, for instance, is a telling passage from the chapter that introduces the pivotal character Madeleine Sicotte, who, in her role as an artist—she is a photographer—can be viewed as a stand-in for the author:

“In the developer tray, a nascent storm emerges where the roiling of the clouds melds with that of the water so that the horizon can barely be made out and it is hard, amid the mirages and reflections, to separate what belongs to the sky from what belongs to the sea. This is the sole subject of Madeleine’s work: the horizon, the boundary between the two worlds, and what manages, unbeknown to scientists and the gods, to travel from one to the other.”

A comparable scene crops up in the penultimate chapter, set in California, a continent away from Madeleine’s home on the Acadian Peninsula in New Brunswick. The landscape is depicted from the point of view of Carmen, who, along with her brother Simon, is central to another of the four narrative strands that Leroux brilliantly braids together: “It’s impossible this morning to tell the sky and mountains apart. The clouds perfectly imitate the hazy crest of the Sierra Nevada so that everything is confused.”

Now, it may seem obvious, but for a translator to do justice to the original he or she must feel an affinity with the work in some fundamental way. The question is: in what way exactly? And the answer, fortunately, is neither obvious nor simple and never identical from one book to the next. I suspect that my affinity with The Party Wall has a lot to do with the intersection between the novel’s manifold exploration of liminality and the fact that the “hazy” dividing line, the interlingual frontier that Wallace Stevens invites us to revisit, is—not surprisingly—both the battleground and playground of translation.

Let’s look at this further description of Madeleine’s work as a photographer:

“She cautiously attaches a macro lens to the camera, which she mounts on a small tripod. Then she positions her arm in front of the lens. For days the only subject that has really interested her is her skin; her shots run the gamut from goose bumps to the crinkles on her water-soaked fingers, as she avidly seeks to penetrate the pores, to pierce the layers of skin as though they are walls keeping her from the truth.”

The skin, then, functions here as the “boundary between [the] two worlds,” of outward appearance and underlying truths. What’s more, the reader soon learns that, contrary to received wisdom, the skin is not the plainly tangible barrier separating self and other, but a porous envelope inhabited by more than one self.

For me, the translator-cum-reader, this powerful image immediately evokes the author’s efforts to climb into the skin of her characters in order to breathe life into them. At the same time, the image mirrors my own struggle as translator-cum-writer to get “under the skin” of the work (or, as Paul McCartney would have it, to let it under my skin) in order to bring it to life, intact yet transmuted, on the English shore of Stevens’s “single” language. I find Maja Haderlap’s poem “Translation” (translated by Tess Lewis) perfectly apposite in this context:

is there a zone of darkness between all languages,

a black river, that swallows words

and stories and transforms them?

here sentences must disrobe,

begin to roam, learn to swim,

not lose the memory that nests in

their bodies, a secret nucleus.

16 November 2016 | in translation |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.