Courtney Elizabeth Mauk’s Characters Are Stronger Together

photo: Jiyang Chen

Courtney Elizabeth Mauk‘s new novel, The Special Power of Restoring Lost Things, introduces us to a family in pain: a mother, father, and son all struggling to cope with the disappearance of their daughter (older sister) Jennifer nearly a year ago. Rapidly moving from one perspective to the next within the story’s tight time frame, Mauk shows us how the three survivors are pushing themselves away from each other—recognizing that that’s what they’re doing but at the same time unable (or perhaps unwilling) to make the necessary course corrections. Here, Mauk explains how a novel about a family grew out of a short story about a mother… and how she was able to manage the sudden shift in scale.

One value I most want to instill in my son is empathy. I hope he grows into a man capable of looking at the world from perspectives not his own, that he develops the capacity to feel the full spectrum of emotions, strives for understanding, and acts with compassion. These are also the reasons why I write. I wouldn’t always have been able to define my writing this way, as an act of empathy, or an attempt to move the world, in some small way, in a more empathetic direction. I would have talked about the storytelling compulsion, a love of words that started in childhood, an urge to create something lasting. And all these things are true too. But at the heart of the matter is feeling. I write because I want to open up human experience, for myself as well as my readers.

This has never been more the case than in The Special Power of Restoring Lost Things. The book began as a short story about the mother of a young woman who has gone missing. I’ve long had a fascination with the missing; it seems confounding that a person can be here and then gone, leaving few traces, especially in this traceable age. I am intrigued by the mystery of the disappeared but even more so by those left behind, grappling for answers in a suddenly altered world. A pivotal scene in the story (which didn’t make the cut to the book) has the mother riding the Staten Island Ferry over and over, held in a literal stasis. I had a vision of her dragging this heavy weight—an indescribable grief with nowhere to land.

22 November 2016 | guest authors |

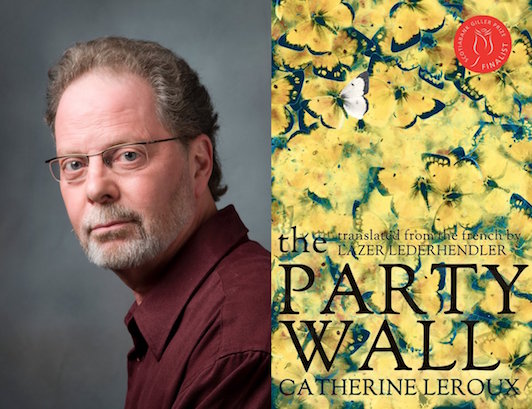

Lazer Lederhendler’s French-English Wall

photo courtesy Biblioasis

Canadian novelist Catherine Leroux’s second book, The Party Wall, won the Quebec Booksellers Prize and the Prix France Québec when it was first published in French in 2014. Lazer Lederhendler’s English-language translation, published this year by Biblioasis, has just won Canada’s Governor General’s Award for translated literature, and it made the shortlist for the Giller Prize for fiction, too. I’m pretty excited about this novel; at first, you don’t know how its various threads, from two young sisters walking through a threatening neighborhood to a Canadian prime minister in what now reads like an all-too plausible dystopian future whose wife uncovers an earth-shattering secret, connect to each other. But Leroux brings everything together in a way that still allows each story to maintain its separate power—you might spend some time trying to guess how she’ll do it, but it’s not going to distract you from the dramas she’s set up for her characters.

Leroux is just one of many Québécois writers Lederhendler has translated in recent years, making this literary scene accessible to English readers. In this guest post, though, he hits upon an idea that makes me think about just how thick (or thin!) we should make any line we draw between Québécois literature and English-language Canadian literature.

In a past life teaching English and, later on, translation in Montreal, I often made a point early in the term of quoting Wallace Stevens’s well-known aphorism, “French and English constitute a single language.” Granted, most people anywhere would find it hard to get their heads around this concept, let alone college students in Quebec, where the relationship between French and English is at the heart of a centuries-old conflict that is far from over.

My aim, though, was not to persuade students that Stevens was right but rather to bring into question some widespread and entrenched assumptions that draw a sharp, dichotomous boundary between the two languages: “English is the language of business, French the language of diplomacy”; “French is difficult, English is easy”; “English is concrete, French is abstract”; “English is demotic, French is elitist,” and such. Whereas to postulate that English and French somehow form one language is to floodlight the overlap, the liminal region where kinships and affinities as well as tensions (the dreaded “false friends” and their kind) are played out.

16 November 2016 | in translation |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.