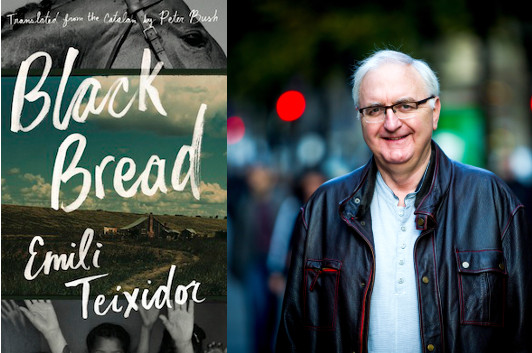

Peter Bush’s No-Hope Sucklers

photo: courtesy Peter Bush

Black Bread is one of those novels that builds slowly, through the accrued detail of seemingly disconnected scenes… or, let’s say, a string of scenes where the narrative throughline is not immediately apparent to the reader. It attracted my attention because I know very little about Catalan culture beyond the fact of its existence, and I wanted to learn. And, too, I wanted to hear from its translator, Peter Bush—who wound up explaining how a novel about rural Catalonia stirred up memories of his own English childhood.

My very first memories are of a sow with the litter of piglets she’d just farrowed. Her sty was in our backyard and she was my first pet. On a Saturday morning in September, 1950, my elder sister walked me up to the Odeon to the kids’ session; when I came back, sections of the sow were hanging from our clothesline and the kitchen was full of blood and entrails. Cousin Ray the butcher had paid us a visit. (In post-war, still rationing Britain, it wasn’t unusual for people to keep pigs and chickens in their backyards, but by 1950, that era was coming to an end.)

Our domestic scene was gloomy for other reasons. My mother had arranged for us to move to a new council house with large gardens and light in a leafier part of town, from anonymous Seventh Avenue to a more optimistic Queen’s Road in the run up to a coronation, and my father had opposed this from the start. He didn’t want to leave the house my battling grandmother had forced out of the council when her husband, a village shepherd, fell ill one Christmas and was evicted along with his family from their tied-cottage by the Tory landowner. (As they bickered, I enjoyed the haslets, chitterlings, black puddings and pork-pies Ray had made from my pet.)

Many other memories, family stories and bits of our rural dialect and oral history kept flooding back as I translated Emili Teixidor’s Black Bread. Of course, pork and pig slaughtering have a different history in Catalunya and the whole of the Iberian Peninsula. The autumn pig slaughter is a time for festivities that are part pagan and part the legacy of an Inquisitional anti-Semitic, anti-Muslim tradition. But that’s not on the mind of the adolescents in Black Bread, as they hear about the deaths of those surplus to the litter, the runts, ‘the no-hope piglets, the no-hope sucklers’ who reach the tit too late: “Cry-baby and I shuddered when we heard those curious details, as if nature had also got it wrong with us, who through lack of tit and lack of parents were also destined to be abandoned and forgotten. No-hope children.”

As a translator of fiction, you co-exist with another’s world and words for months, if not years. As you re-draft, re-read, re-write, they dig into your own consciousness and re-kindle words and worlds of your own that suddenly surface to help the process of translation, sparking surprising points of contact across the otherness of a different language and history, and reflections on the similarities and the antagonism.

Teixidor’s narrator, Andreu, recounts his experiences of growing up on his grandmother’s farm in the remote Catalan countryside after the civil war, away from his father, an anti-Francoist militant, and his mother, a textile factory worker, who were never going to be at home enough to look after their son. There are memories of climbing trees, wandering through woods, musing about animals and sexual awakening with his two cousins, Quirze and Cry-Baby, and their friend, Oak-Leaf, an almost lush pastoral, punctuated by jarring encounters: the eviscerated carcass of a dead horse, Mad Antònia running through the trees, stark-naked, gone crazy ever since a civil guard interrupted coitus with her boyfriend among the hay and executed him on the spot, the civil guard swimming naked in a lake or emerging sweaty and smiling from a leafy arbour with Aunt Enriqueta, a seamstress, a woman who is liberated to the extent that she works in a nearby town, and has opted out of dawn to dusk working on the land.

Black Bread is a novel Teixidor wrote at the age of seventy, and as I translated, I felt it read like a narrative that had been years in the making, a coming to terms with his own past, fiction steeped in the experience of war and dictatorship as in the novels of Joan Sales and Mercè Rodoreda. He begins with a quotation from the Spanish writer, AgustÃn GarcÃa Calvo, about history as a quantifying and categorizing of reality that one feels isn’t true; the time comes when events one has lived are explained in a way that doesn’t ring true.

Well, Andreu’s narrative does ring true, recreating the complexities of those years through a tissue of stories told by himself, Oak-Leaf, Grandmother, Quirze, his aunts, uncles, mother and the labourers hired for the harvest. It’s a symphony of voices and thwarted energies suppressed in a police-state where adults spoke in riddles and children had to learn to read between the lines, choosing between Catalan or Spanish, depending on their interlocutor, and then seeking out the adjective, the nuance, the intonation that betrayed whether someone was on ‘our’ side or not. Grandmother is sure that when the Allies defeat Hitler and Mussolini, they will come for the Spanish dictator. They didn’t and, with their complicity, the police-state was to last another thirty years. Andreu can’t become a scholarship boy, he has to sell his soul.

11 September 2016 | in translation |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.