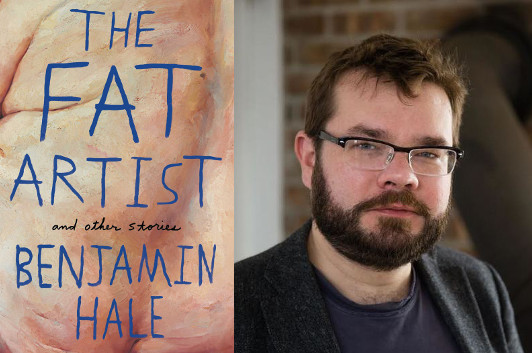

Benjamin Hale & “A Game of Clue”

photo: Pete Mauney

I liked Benjamin Hale‘s The Evolution of Bruno Littlemore, which I reviewed for Shelf Awareness, and I was eager to see what he’d do next. After all, a nigh-Nabakovian novel narrated by an intelligent chimpanzee is a hard act to follow—but The Fat Artist and Other Stories doesn’t disappoint. These stories are more naturalistic… well, okay, “The Fat Artist” exists in that twilight zone between absurdism and science fiction that Robert Sheckley used to detail so masterfully. But there are other great stories in here, like “If I Had Possession Over Judgment Day” or “Leftovers,” that take place in a world as real as real could be, even when events go to their most extreme. One of the things I particularly enjoy about this collection is that Hale gives his stories room to play out; it’s something he talks about in this guest post, in the context of one of his own favorite stories.

Steven Millhauser is one of two writers of whom I can say this: Whenever he publishes a new book, I drop whatever else I’m doing and immediately buy it and read it. (The other is Nicholson Baker.) I discovered Millhauser’s fiction in my early twenties, when someone recommended I read his first novel, Edwin Mullhouse: The Life and Death of an American Writer, 1943-1954, by Jeffery Cartwright. The local bookstore didn’t have it, but they did have The King in the Tree, a collection of three novellas that had just come out. I bought it, took it home, and within a few pages I was beginning to understand that I had opened the work of a writer who spoke directly and with rather uncanny precision to me, who clearly derived the same sort of pleasures from literature as I do.

In Millhauser, I found a very American writer who crafts Borgesian structures out of Nabokovian wit and wordplay, with as much humor and perhaps even more humanity than either Borges or Nabokov. Later, I did read Edwin Mullhouse (I hate hyperbole, but I consider that book to be one of a handful I can think of by living writers that I would call a “masterpiece”), and the rest of his published fiction, too.

Millhauser is a master of both long and short-form prose fiction, as well as a hybrid animal, the longish story/shortish novella. This might be my personal favorite form for prose fiction—both to read and to write. (The Fat Artist contains just seven stories, all of them on the long side, and a few of which are novella-length.) “The problem with stories,” I once heard Charles D’Ambrosio say, “is that they have to be efficient. Stories that aren’t efficient are novels.”

The pleasures of a novel—becoming absorbed in a story’s world, coming to know characters well and invest in them, following a long, immersive plot that unfurls patiently—are often not the pleasures of short fiction, in which the puppets don’t have much time to spend onstage before the author must jerk their strings, get them up and dancing. Long stories allow us to have it both ways: more efficient than a novel, but more space to flesh out the characters and the world around them than a short story offers.

Unfortunately these stories are usually too long for magazines—you would never see one (anymore) in The New Yorker—and too short to publish individually, making them perhaps the least saleable form of prose fiction. But the long story has been the most comfortable swimming hole for plenty of great writers: Alice Munro, Harold Brodkey, Kafka—and Steven Millhauser.

One of my favorite stories of all time is the first one in Millhauser’s The Barnum Museum, a fifty-page family epic in miniature titled “A Game of Clue.” Characteristic of Millhauser, it’s a kaleidoscopic vortex of mise en abyme about a middle-class family somewhere in suburban Connecticut sitting around a card table on a screened porch late at night playing the board game Clue. The players: Jacob, a twenty-five-year-old graduate student visiting his family on his little brother’s birthday; Susan, Jacob’s girlfriend, a little boring, nervous, not of the tribe, brought along on the trip at the last minute; Marian, Jacob’s younger sister, put-out with Jacob for arriving late and bringing the girlfriend; and David, their teenage kid brother, the birthday boy who adoringly idolizes his older brother, and is the most enthusiastic player of the game. Below the surface of the board, in a foggy realm supplied by the players’ imaginations, Colonel Mustard, Miss Scarlet, Mr. Green, Professor Plum, and Mrs. Peacock are locked in their own crisscrossing currents of mistrust, conquest, desire, and obsession.

The story—as many of Millhauser’s best are—is a playful meditation on the psychological mechanics of narrative. A narrative exists in a space imagined by two or more people at once. Among games (as in literature), there is a continuum between the abstract—with, for instance, Go on one extreme end—and the concrete#8212;Dungeons and Dragons might be on the other end of the line; Clue is a very concrete, very narrative game. It asks its players to take the flat board of squares and rectangles representing rooms—the Billiard Room, the Dining Room, the Conservatory, the Library—and imagine a sprawling English country mansion. Each player—each reader—of the game uses the imagery and information available to him or her (experience, including second-hand experience from books and films) to imagine the space and the characters that inhabit it. The shared space of the narrative differs from one player to the next depending on each player’s set of memories, experiences, strength of imagination, particular points of interest, and investment in the narrative.

Millhauser’s disembodied, omniscient narrator floats above the heads of the characters, sometimes describing objective “reality” with scientific detachment and precision, sometimes descending into their consciousnesses, their memories, their motives, their dreams. It ultimately becomes a sweet, almost sentimental story about an unhappy but genuinely loving family fearing for their father in his rapidly failing health. On the highest of the several layered planes of narrative, the emotions they all share are dread and persevering love for their parents and for each other.

“A Game of Clue” is a coldly, inhumanly told story that glows from within with a deep, red, human warmth. Toward the end, Jacob toasts to his brother’s birthday, and David thinks, “He would like to tell them that they can count on him, that he will take care of them, that everything will be all right: Jacob will be famous, Marian will be happy, Susan will marry Jacob, Dad will never die. He knows that the words are extravagant and says them only to himself. ‘Thank you,’ David says. For a moment, it’s as if everything is going to be all right.”

9 August 2016 | selling shorts |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.