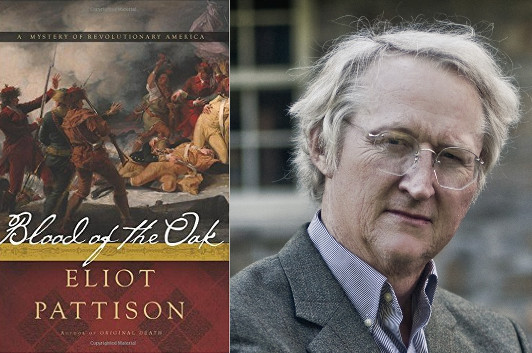

Eliot Pattison: The Power of the Historical Novel

photo: Ted Ferguson

If you’re a fan of hardboiled detective fiction, I’ve got a left-field recommendation for you: Eliot Pattison‘s Blood of the Oak is a historical novel, set in pre-Revolutionary America. It’s the fourth novel in a series featuring Duncan MacCallum, who came to the colonies as an indentured servant but now lives on the edge of Britain’s penetration into the New World. In this story, he’s compelled by both a request from a dying Iroquois friend and an attack on a British comrade to investigate a series of brutal murder and, much like our modern private eyes and single-minded police, slowly but surely finds himself wading into deep tides of corruption and evil. I’m as engrossed by this plot as I’ve ever been by a Robert B. Parker or Michael Connelly novel, and Pattison’s fantastic at making 1760s America feel simultaneously strange and familiar. Which, as he explains in this guest post, is something he works hard to accomplish…

America has misplaced her history. Studying our past has been dropped from many required curricula in our schools, and our students score lower in history than any other subject—which should come as no surprise to anyone who has turned the sterile pages of modern texts. Those pages squeeze the life out of history, rendering it an arid dump of dates and statistics, as if the story of mankind were just a scientific experiment of interest only to technicians.

But we are not composed of dates and data, we are not constructed of factoids to be reduced to graphs and charts. The DNA that makes us possible was bestowed on us by people who lived incredible lives, who endured unspeakable adversities, engaged in staggering adventures, suffered abject tragedies and celebrated boundless joys. We all swim with them in the same great ocean of humankind, separated not so much by beliefs, appetites, and interests as by technology and time.

Stories of our forebears and tales of the struggle to be human have been a vital part of every culture. They are part of our spiritual DNA, and our institutions have failed us by ignoring them. We are diminished by losing that connection with our ancestors. Our cultural gurus preach self-awareness but how can we be self-aware if we don’t even understand the legs we stand on? If you don’t know history, novelist Michael Crichton once observed, “you’re just a leaf that doesn’t know it is part of a tree.” We have historical novels because our history books and our history classrooms are just not good enough.

I write and I read historical novels to embrace the richness of the human story. I don’t want to simply be told that Marco Polo visited Asia in the 13th century, I want to hear the braying of his camels along the ancient Silk Road and feel his awe as he enters the Chinese capital. Years ago I read a history of early America whose only treatment of the amazing Iroquois confederation was a timeline that noted its collapse in the mid-18th century. That dismissive note regarding one of the most remarkable cultures of North America lit a slow burning anger that became one reason I began writing novels set in that period.

I don’t want a vital people reduced to a date, I want to see the tears of Iroquois widows and hear the slow, melancholy beat of their tribal drums. Don’t just tell me that Leif Ericsson came to America in 1001; make my eyes sting from the salt spray off the bow of his Viking ship. These people were as alive as you and I. These people became us. Their lives are pages in the human story, the genes that make up that spiritual DNA that survives in all of us. History books are unable to convey that essence but thankfully, as Emerson reminded us, “fiction reveals truth that reality obscures.” This is the glory, and the duty, of the historical novelist.

Those of us who anchor our work in distant times can sense that glory as we peel away the layers that obscure the past—but we must also feel the responsibilities that come with exploring that truth. That duty isn’t simply about being factually accurate. Accuracy and honesty in conveying our settings and characters are vital—without them we not only lose our readers, we damage the genre. But authenticity is about more than just fact checking. Any writer can make a character walk and talk but only when we know the character’s motives, mannerisms, dress, affections and affectations does he or she come to life. Constructing these elements in a distant day and place is a formidable challenge. It means laborious immersions in the sea of time, but when the author emerges, dripping with insight, the successful translation of setting and character across centuries can be a tour de force.

Ultimately it is such translation that is the real power of historical novels. Without that translation the ancient Japanese tea ceremony becomes just another way to imbibe caffeine. With it, an act of grace and beauty performed hundreds of years ago can still resonate within us. The best historical novels let us swim in the vast human sea, unrestrained by time.

27 March 2016 | guest authors |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.