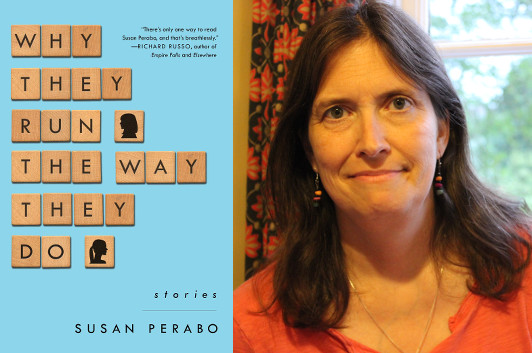

Susan Perabo & Wolff’s Audacious “Bullet”

photo: Sha’an Chilson

The short story Susan Perabo has chosen to write about is one of my own favorite short stories, and the thing that draws her to that story is similar to what draws me to “This Is Not That Story,” one of the stories in her new collection, Why They Run the Way They Do. Perabo plays with our recognition of the act of reading a short story, of the expectations that we bring to such an experience, of how it will be told and what it will tell us, and yet when she dodges and weaves past those expectations, the self-consciousness is barely visible, and never distracting. The metafictional elements are front and center, yet it’s the fictional components that have stayed with me long after I’ve finished reading. In her other stories, her technique calls even less attention to itself, but remains at that consistent level of excellence. If you care about short stories, Susan Perabo should be on your radar—if she hasn’t been before, then you’re in for a great surprise.

Great short stories happen to you. In this way, stories are more like poems than like novels. A short story is a singular, uninterrupted experience, an event, occurring all at once. If you are someone who is passionate about literature, you probably have at least one story that’s so profound an event in your life that you recall where you were when you first read it, in the same way you recall where you were when you received some important, life changing piece of news. In the case of the story, maybe your whole life didn’t change, but your reading life, or your writing life did.

One story that happened to me is Tobias Wolff’s “Bullet in the Brain.” I was at my job as a literature tutor for the intercollegiate athletes at the University of Arkansas. I was in the women’s study hall, located in the old Barnhill Arena. I was “on call,” which meant I sat around reading magazines until a student needed to talk with me about Oedipus or Gatsby or Marvell’s coy mistress. Most nights I was in the men’s study hall and worked pretty much nonstop, but once a week I was in the women’s study hall and had a lot of time to read. (Not a judgment—just an observation.)

The reading I had that night was the September 25th, 1995 issue of The New Yorker. It included the story “Bullet in the Brain,” which I noted happily was only three pages long. This was good because it meant I likely could read it without interruption.

“Bullet in the Brain” follows the last few minutes of life, and the first few nano-seconds of death, of the book critic Anders, a pompous blowhard who is so amused by his own cleverness that, in the midst of a bank robbery, he endangers himself and everyone else in the bank by ridiculing the bank robbers for being hopelessly clichéd. Eventually realizing there’s only one way to get Anders to shut up, one of the robbers shoots Anders in the head, setting off a chain reaction of “synaptic lightning” in in which Anders’ life, “in a phrase he would have abhorred,” flashes before his eyes.

I’ve decided that the only single word that can possibly define this short story is “audacious.” I’ve read the story maybe forty times in the last twenty years, and I still can’t believe Wolff pulls it off. The tightrope Wolff walks, bridging the gaping canyon of sentimentality that this story should be, is so thin as to be invisible. Only through sheer audacity could a writer take this character, and this plot, and create something this good.

Perhaps the most audacious moment in the story is when Wolff, clearly recognizing he needs to develop his main character beyond the total jackass we’ve seen if he has a prayer of delivering the ending he wants, gives us the following sentence: “It is worth noting what Anders did not remember, given what he did remember.” No teacher among us would allow a student to get away with a sentence like that, and likely no writer among us would dare to be so blatantly telegraphed about our character development. But it’s precisely the straightforward, unapologetic nature of this sentence that makes it work. We’re then treated to one of the finest three-paragraph life summaries in contemporary literature, a textbook study of character detail that leaves us with the sense that we now know Anders thoroughly, that he is every bit as complicated as we are, that the jackass is merely the tip of a troubled, funny, frightened, loving, envious, passionate iceberg. Then, with the steam built from those paragraphs, his confidence high, Wolff launches himself into his audacious closing with these words: “This is what he remembered.”

Perhaps you know how the story ends. If not, I’m not going to tell you, because I couldn’t do it justice. I’m going to ask instead that you find it—easy enough to do—and read it yourself.

I will tell you this, though. After I finished the story, not only did I not know where I was, I’m not sure if I knew who I was. Twenty years later, I recall this sensation vividly, standing up from my chair, magazine in hand, and looking around that room at the young athletes doing their homework. Who were they? What had brought me to this room with them? I was literally dizzy, my head spinning and my knees wobbly, suspended between two worlds, Anders’ baseball field of they is, they is and the Barnhill Arena study hall.

I walked out of the room, down the quiet corridor, and into the 10,000-seat basketball arena, which was entirely empty. In that moment the arena was as powerful, as rich with meaning, as an ancient cathedral or a open meadow or deep space. I stood in that vast silence and reconsidered what a story could do.

7 March 2016 | selling shorts |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.