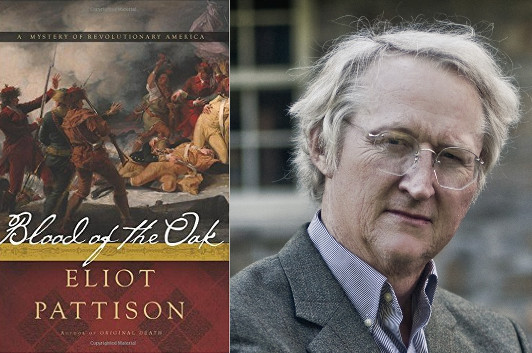

Eliot Pattison: The Power of the Historical Novel

photo: Ted Ferguson

If you’re a fan of hardboiled detective fiction, I’ve got a left-field recommendation for you: Eliot Pattison‘s Blood of the Oak is a historical novel, set in pre-Revolutionary America. It’s the fourth novel in a series featuring Duncan MacCallum, who came to the colonies as an indentured servant but now lives on the edge of Britain’s penetration into the New World. In this story, he’s compelled by both a request from a dying Iroquois friend and an attack on a British comrade to investigate a series of brutal murder and, much like our modern private eyes and single-minded police, slowly but surely finds himself wading into deep tides of corruption and evil. I’m as engrossed by this plot as I’ve ever been by a Robert B. Parker or Michael Connelly novel, and Pattison’s fantastic at making 1760s America feel simultaneously strange and familiar. Which, as he explains in this guest post, is something he works hard to accomplish…

America has misplaced her history. Studying our past has been dropped from many required curricula in our schools, and our students score lower in history than any other subject—which should come as no surprise to anyone who has turned the sterile pages of modern texts. Those pages squeeze the life out of history, rendering it an arid dump of dates and statistics, as if the story of mankind were just a scientific experiment of interest only to technicians.

But we are not composed of dates and data, we are not constructed of factoids to be reduced to graphs and charts. The DNA that makes us possible was bestowed on us by people who lived incredible lives, who endured unspeakable adversities, engaged in staggering adventures, suffered abject tragedies and celebrated boundless joys. We all swim with them in the same great ocean of humankind, separated not so much by beliefs, appetites, and interests as by technology and time.

Stories of our forebears and tales of the struggle to be human have been a vital part of every culture. They are part of our spiritual DNA, and our institutions have failed us by ignoring them. We are diminished by losing that connection with our ancestors. Our cultural gurus preach self-awareness but how can we be self-aware if we don’t even understand the legs we stand on? If you don’t know history, novelist Michael Crichton once observed, “you’re just a leaf that doesn’t know it is part of a tree.” We have historical novels because our history books and our history classrooms are just not good enough.

27 March 2016 | guest authors |

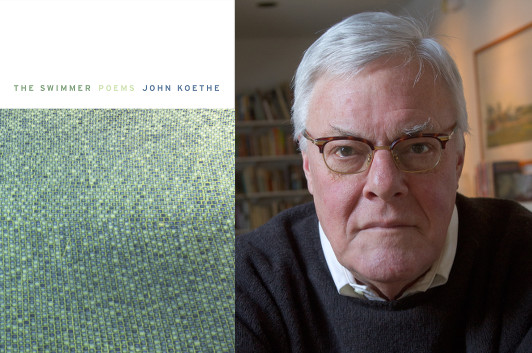

John Koethe and the Poetic Sentence

photo: Tom Bamberger

The poems in John Koethe’s The Swimmer are like personal essays, a mixture of autobiographical anecdote and layered references to literature, art, science, and philosophy. And one of the first things you’ll notice about the cadence of those poems is its similarity to prose—but it’s not a “ordinary sentences peppered with random line breaks” kind of banal, descriptive poetry; these are complex, intricate sentences that, as Koethe explains in this essay, aim to mirror the processes of recollection and reflection that shape our memories, and the ways we come to see what we have experienced through what we have learned. There is no memory without interpretation, and as we re-interpret our pasts, we are also re-defining our present.

I started writing poetry in 1964 as a sophomore in college, after a course on modern literature in which I first read the poets of high modernism. I wasn’t sure exactly what they were doing, but I was bowled over by it and knew I wanted to try to do it too. Learning to write poetry is at first a process of imitation—especially back then, before the proliferation of programs in “creative writing” (how I hate that term!)—and while my first models were Eliot (whom I still revere) and Pound (whom I don’t care for anymore, apart from his Chinese (non)translations), that circle soon expanded to include Wordsworth and Keats, John Ashbery and James Schuyler, Wallace Stevens, Marianne Moore and Elizabeth Bishop, and later on Philip Larkin; as well as fiction writers like Proust, Fitzgerald, Thomas Pynchon and even Raymond Chandler.

What these writers have in common is that they’re all great writers of sentences, and sentences are at the heart of what I’m after in poetry, perhaps to a greater extent than they are for many other poets. What I try to do is capture the feeling and movements of thought, and not only are sentences the vehicles of thought, their clauses and connectives allow them to convey the rhythmic and emotional cadences that are an integral part of the experience of thought.

With any luck you eventually digest your early influences, for better or worse, and it’s been many years since I’ve been aware of a feeling of being guided in my writing by the work of other writers. Yet those first influences remain important to me as an ideal, or an idea, of how to think of poetry. I think of modernism as a continuation of, rather than a break with, romanticism, in that both are concerned to situate the inner self in relation to its objective social and physical setting in the world. In its high romantic incarnation, this concern takes the revelatory form of what Kant called the experience of the sublime; in its disillusioned modern incarnation it verges on the tragic.

20 March 2016 | poets on poets |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.