How Sandra Smith Became a Translator

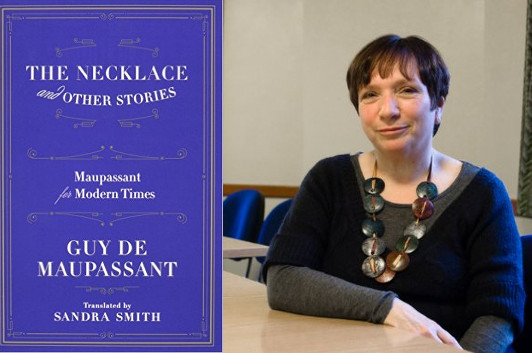

photo courtesy Sandra Smith

I confess that I have huge gaps in my reading of the world literary canon, including just about all the French classics. But I’ve begun to remedy that situation, at least with respect to Guy de Maupassant, thanks to The Necklace and Other Stories, a collection of stories described by its publisher, Liveright, as a “Maupassant for Modern Times.” The translator, Sandra Smith, turned out to have an interesting path to this project, a path that involves one of the biggest successes for a posthumously published novel in translation in recent memory.

As an academic teaching French language and literature at Cambridge, I was always involved with translation in a practical sense. The historians, to whom I taught grammar and translation, were required to pass a language examination at the end of the first year. My real goal, however, was to prepare them to be competent enough to use their language skills to research original sources and documents written in French.

One of my favorite texts to use was Camus’ Lettres à un ami allemand. A little-known work written during the Occupation, it is a brilliant combination of literature, philosophy, history, rhetoric and propaganda. I decided I wanted to translate the work into English and approached a publisher. After a few months, they said they thought the work “too academic” for their list, so I set the project aside.

Nearly two years later, I was listening to BBC Radio 4 and heard Rebecca Carter of Chatto & Windus talking about Suite française. I was immediately fascinated by the similarities between Irène Némirovsky’s family history and my own. More importantly, however, I was certain that a translation of Lettres would make an excellent “accompaniment” to the English publication of Suite française. It was a sign: I looked up Chatto & Windus on the internet and phoned Rebecca Carter.

During our conversation, I stressed how well the two translations would work together and Rebecca told me to send her my sample translation. We then began discussing the similarities between my own background and Némirovsky’s. I was Jewish, my grandparents had left Europe due to the pogroms and I was an immigrant myself. By the end of the conversation, Rebecca asked me if I would be interested in submitting a sample translation for Suite française, with the understanding that it was highly unlikely I would be offered the contract. She was gathering samples from established translators but the majority were men; she wanted some samples from women as well.

I had no experience whatsoever in translating fiction; my published translations at the time consisted of four chapters of a Cambridge University Press book on medieval French history, an art catalogue and some reports for the European Union. Rebecca explained that all the translators would be submitting the same chapter. (I subsequently learned that this process is known in the trade by the unfortunate label of a “beauty contest.”) One month later, I was short-listed as one of the final three candidates and asked to translate an additional few pages. I realized that the publishers would be taking an enormous risk offering this work to me when so many other experienced translators were in the running. To my great surprise, Rebecca told me I had been awarded the contract: they were prepared to take the risk.

Irène Némirovsky’s exquisite writing combined with her personal story made Suite française an immediate success when published posthumously in France in 2004. Her background was widely discussed and celebrated: her family’s flight from Russia during the Revolution, her success as a writer in France in the 1930s and her subsequent deportation and murder at Auschwitz. My own family’s background was similar to hers, although, fortunately, without the tragic ending.

In my mind, the similarities between Némirovsky’s experiences and my own created a bond of empathy that was crucial in translating her works: both women, mothers, immigrants, secular Jews, forever foreigners. Although English is my native language and I lived in England most of my adult life, my American accent meant that others still regarded me as foreign. Némirovsky, who spoke French fluently, wrote in French and lived in France most of her adult life, was never granted French citizenship and died a “stateless person.” (Ironically, it is only since 2004 that she is being hailed as a great “French” writer.)

To any translator, the most obvious given is that the translation process is inevitably subjective. Even reading in one’s own language involves a translation process, as individuals react subjectively to the written word. An essential part of the reading process is the individual’s interpretation—“translation”—of the writer’s words and its transformation into an emotional or intellectual response. This process occurs continually in everyday life: we “translate” whenever we read each other’s tone of voice, facial expressions, body language, and draw subconscious conclusions as to the meanings of those elements. The same process applies to other arts: painting, music, dance. We are all translators in the sense that we interpret sensory symbols and react with either a rational or emotional response that, by definition, must be subjective.

In terms of style, however, I realized that I could use my experience in teaching literature to analyze and reproduce an equivalent style between the French and the English. Stylistic elements can be more objectively analyzed and quantified than subtleties of tone and subtext. Translating fiction first requires analysis: understanding a literary, cultural and historical context, sensitivity to tone, plays on words, lyricism, alliteration, assonance, register, idiom, an ability to grasp the psychology of characters and the skill to aptly analyze dialogue and dialect. I felt it essential to focus on each of these factors in order to do justice to Némirovsky’s works.

The success of Suite française allowed me to truly become a literary translator. I subsequently translated eleven more novels by Némirovsky, a new version of Camus’ L’Étranger (published in the UK as The Outsider in 2012), The Necklace and Other Stories, and have four books coming out next year. I have been extremely fortunate to be able to continue in a career I dearly love.

20 December 2015 | in translation |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.