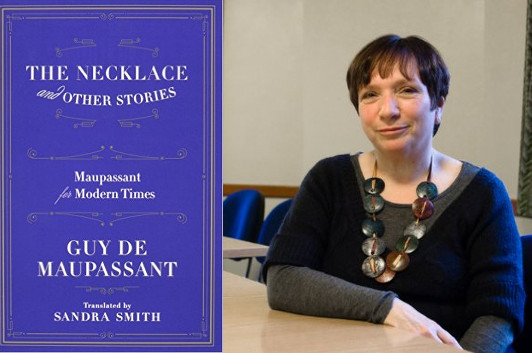

How Sandra Smith Became a Translator

photo courtesy Sandra Smith

I confess that I have huge gaps in my reading of the world literary canon, including just about all the French classics. But I’ve begun to remedy that situation, at least with respect to Guy de Maupassant, thanks to The Necklace and Other Stories, a collection of stories described by its publisher, Liveright, as a “Maupassant for Modern Times.” The translator, Sandra Smith, turned out to have an interesting path to this project, a path that involves one of the biggest successes for a posthumously published novel in translation in recent memory.

As an academic teaching French language and literature at Cambridge, I was always involved with translation in a practical sense. The historians, to whom I taught grammar and translation, were required to pass a language examination at the end of the first year. My real goal, however, was to prepare them to be competent enough to use their language skills to research original sources and documents written in French.

One of my favorite texts to use was Camus’ Lettres à un ami allemand. A little-known work written during the Occupation, it is a brilliant combination of literature, philosophy, history, rhetoric and propaganda. I decided I wanted to translate the work into English and approached a publisher. After a few months, they said they thought the work “too academic” for their list, so I set the project aside.

Nearly two years later, I was listening to BBC Radio 4 and heard Rebecca Carter of Chatto & Windus talking about Suite française. I was immediately fascinated by the similarities between Irène Némirovsky’s family history and my own. More importantly, however, I was certain that a translation of Lettres would make an excellent “accompaniment” to the English publication of Suite française. It was a sign: I looked up Chatto & Windus on the internet and phoned Rebecca Carter.

During our conversation, I stressed how well the two translations would work together and Rebecca told me to send her my sample translation. We then began discussing the similarities between my own background and Némirovsky’s. I was Jewish, my grandparents had left Europe due to the pogroms and I was an immigrant myself. By the end of the conversation, Rebecca asked me if I would be interested in submitting a sample translation for Suite française, with the understanding that it was highly unlikely I would be offered the contract. She was gathering samples from established translators but the majority were men; she wanted some samples from women as well.

I had no experience whatsoever in translating fiction; my published translations at the time consisted of four chapters of a Cambridge University Press book on medieval French history, an art catalogue and some reports for the European Union. Rebecca explained that all the translators would be submitting the same chapter. (I subsequently learned that this process is known in the trade by the unfortunate label of a “beauty contest.”) One month later, I was short-listed as one of the final three candidates and asked to translate an additional few pages. I realized that the publishers would be taking an enormous risk offering this work to me when so many other experienced translators were in the running. To my great surprise, Rebecca told me I had been awarded the contract: they were prepared to take the risk.

20 December 2015 | in translation |

Lillian Ann Slugocki’s Literary Love Letter

photo courtesy Lillian Ann Slugocki

I’ve known Lillian Ann Slugocki since 2001, when I interviewed her and Erin Cressida Wilson about their collaboration on the dramatic monologues of The Erotica Project; more recently, Lillian wrote an essay for Beatrice about expanding an online serial into the novella The Blue Hours. Now she’s written a new novella, How to Travel with Your Demons, and, to celebrate its launch, she’s curated a night of new work by other women writers at New York City’s KGB Bar, on Tuesday, December 22. I’m planning on being there, and if you’re in the neighborhood, I hope you’ll drop in as well.

In the spring of 2013, I had this notion to write a book where I broke all the rules regarding point of view, but still created a compelling and cohesive narrative. I figured I could do that if I kept the plot super simple. The protagonist, Leda, must travel from point A to point B—and like Odysseus, stuff happens along the way. But I would write the story from the protagonist’s point of view, the author’s point of view, and a third person narrator as well. I was interested in both the intersections and the disruptions:

The seatbelt signs are on, like a constellation over everyone’s head. It is a sleek piece of machinery cutting through the night sky and the winter storm, just skirting the edges of a crescent moon. Almost ready to crash into the Pleiades. Or Orion. Barely visible from the cloud cover—which extends two hundred miles north and south. But still nothing can be stopped in its trajectory. Not this plane, not even the woman sitting in Aisle H, seat 589. She believes that this started with a phone call when she walked out of the deli yesterday. She believes that it started when it was snowing this morning in Brooklyn, waiting for her car to arrive, but the truth is, this journey began a long time ago.

I’ve belonged to Fictionaut, an online community, for about six years. I’ve met some great writers there. It’s like a more intimate version of Wattpad, it’s not open to the public, and members are invited. I posted the first 300 words in the spring. It got 447 views, six favs, and eight comments. Bill Yarrow wrote, “Very Robbe-Grillet, and that is high praise.” I researched everything I could find on Robbe-Grillet, and bought a couple of his books. In other sections I posted, Carol Reid loved the way the narrative telescoped down into each moment. Sam Rasnake liked the “sky-scape,” George Korolog enjoyed “the conjunction of airplanes, metaphysics and the ethics of mortality,” and Beate Sigriddaughter said the writing is marvelously breathless. In all, I workshopped six sections, 10,000 words, and with each round of comments from my peers, I discovered the heart of the book. I moved away from posting excerpts for review and finished the first draft of How to Travel with Your Demons in the summer.

17 December 2015 | guest authors |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.