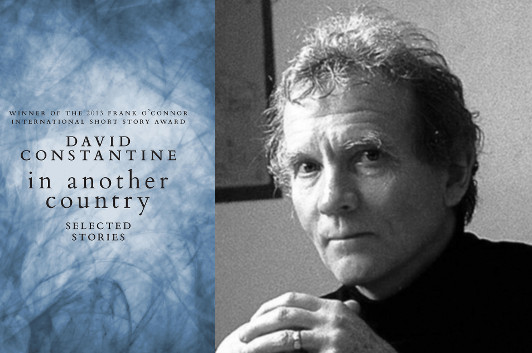

David Constantine: A New Center of Attention

When you start reading In Another Country, it’s the precision of David Constantine’s prose that gets you first. His descriptions, his dialogue—it’s all so unnervingly exact, dropping you into scenes that are both immediately recognizable and profoundly unsettling. And one consequence of this exactitude is that you simply can’t skim a Constantine story. There’s that school of thought that every detail in a short story should be an essential detail, but actual stories live up to that theory to varying degrees—the point being that Constantine’s best work, as represented in this career-spanning collection (which includes stories from the Frank O’Connor International Short Story Award-winning Tea at the Midland), hits that mark with riveting consistency. In this guest post, he explains the purpose behind this careful approach to language, a literary purpose that’s equal parts aesthetic and philosophical.

The phrase is Lawrence’s: “The essential quality of poetry is that it makes a new effort of attention.” So does fiction. And, doing it, poems and stories ask us to do the same: attend better. I associate that demand with Lear’s shocked utterance when he is evicted out of kingship onto the heath and begins to notice that the poor have a hard time of it: “O, I have ta’en / Too little care of this …” We all take too little care. Fiction and poetry jolt us into caring more. They widen our sympathy.

In practice the new effort of attention will most often have a polemical edge because it will alert us to the state we are in. The declaration that citizens have the right to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness cannot be un-declared. So, alerted, paying attention, we look around us and see, at best, that the aspiration has been very imperfectly realized, and, at worst, that much has been done to make its realization unlikely or downright impossible.

Fiction and poetry continually remind us that we do not (are not permitted to, don’t try hard enough to) live as connectedly, wholly, humanely as we might. They help us imagine a livelier life.They do this intrinsically first by practising the autonomy without which no artistic creation is possible. That autonomy contradicts and challenges the unfreedom which in various forms (some more obvious than others) reduces our lives in society. And secondly, a poem or story unsettles us by its own truth and beauty because it confronts us with that famous pairing all too often in circumstances of very great ugliness and mendacity (trashed environment, debased public discourse and conduct, for example). Fiction and poetry by their intrinsic workings urge us not to give up the hope of freedom, truth and beauty. In fact, they incite us to revolt.

Some writers show through the plot itself, in the feelings and actions of certain characters, what revolt against life-reducing circumstances would be like. Lawrence does this, often through his women—in “The Daughters of the Vicar,” for example. Here is the “profession de foi” of one of those daughters, and on it she acts:

‘They are wrong—they are all wrong. They have ground out their souls for what isn’t worth anything, and there isn’t a grain of love in them anywhere. And I will have love. They want us to deny it. They’ve never found it, so they want to say it doesn’t exist. But I will have it. I will love—it is my birthright.”

That’s one strategy, very exciting.

Another, perhaps more “realistic,” consists in showing a social order in which an autonomous life, especially for women, is almost impossible and “the death of the heart” very likely. Elizabeth Bowen and Jean Rhys typically work like that. In Bowen’s “Sunday Evening,” for example, horror seeps through as soon as the women’s efforts at conversation falter. In their heads they wonder how much more they can stand. But they don’t revolt. The reader must do it for them. The reader feels: “If this is so, it is intolerable.” Jean Rhys’s stories show women doing their best in circumstances made by men and enforced by men precisely to thwart women in their will to live lives they can call their own. Very truthful, Rhys shows how little room to manoeuvre her women have: “A woman must, a woman shall or a woman will.” How demeaning and restricting are the roles on offer to them. In “Mannequin,” there are twelve types of woman—the blonde enfant, the gamine, the garçonne, etc.—to please twelve types of client. Women are forced into compliance, their lives are warped by it. And how merciless they become to one another in their competition for favours from the men who hold the power.

Literature shows us how by choice or perforce we behave. And helps us to imagine something better. After my fashion, I try to do that in my own stories and poems and I have for decades read, loved and learned from scores of eminent practitioners, such as those I have spoken briefly about above.

14 June 2015 | selling shorts |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.