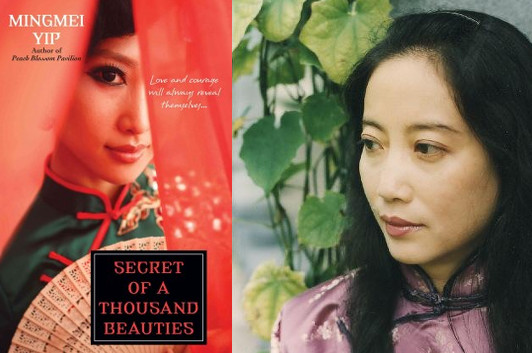

Mingmei Yip: Threads of the Past

photo: MingmeiYip.com

Mingmei Yip has been a guest reader at Lady Jane’s Salon, the monthly romance reading series I help curate, on several occasions, and she joined us at the start of 2015 to share an opening scene from her most recent novel, Secret of a Thousand Beauties. She tells us a little bit about the historical origins of this book’s story here, but also stretches back into her own past to reveal how she set out on the writing path… a journey that takes a bravery and self-determination similar to that of the women she’s written about.

In traditional China, women were and sometimes still are considered men’s possessions and didn’t have much independence or freedom. A Chinese saying goes: “The worst thing that can happen to a woman is to marry the wrong man. The worst thing that can happen to a man is to enter the wrong profession.†Unfortunately, because marriages were usually arranged, many women ended up marrying the wrong man at the cost of any chance for happiness. Wary of a bad marriage, some decided to remain single for the rest of their life. These women would join small communities established for non-marrying women. They displayed this choice by tying up the hair in a long pigtail.

Most worked as maids, but some were more fortunate and could learn a traditional woman’s craft. One of these was embroidery, an art that has always appealed to me. Intrigued by these women and their sisterhoods, I decided to write about this small group of embroiderers—they are supposedly celibate, but of course many succumbed to desire.

Ghost marriage was another way women were oppressed in traditional China. Couples were often betrothed in childhood, or even before birth. Since only half of children survived to adulthood, many young women lost their fiancés. Because they had already pledged marriage, the cruel custom was to marry the woman to the dead man. As a practical matter, this meant she was a slave to her supposed in-laws.

19 January 2015 | guest authors |

Historical Fantasy on the YA Shelf: Robin LaFevers’ His Fair Assassin

I first learned about Robin LaFevers’ His Fair Assassin shortly before the publication of the first novel in the series, Grave Mercy, in the spring of 2012. As a fan of both fantasy and medieval history, I was intrigued by the idea of a convent of mystical assassins in 15th-century Brittany, young women trained since early childhood as killers in service to a pagan god of death camouflaged as a Catholic saint. As curious as I was, though, I didn’t get around to reading it then… which, it turns out, would help me appreciate the scope of LaFevers’ trilogy by experiencing it all at once.

When the final book in the trilogy, Mortal Heart, was published in late 2014, I resolved to take on the books. The first thing I realized, very soon into Grave Mercy, is that although the series has been presented to American audiences as young adult fiction—and is an absolutely solid success on that level—it might just as easily have been framed as an “adult†fantasy trilogy that just happens to feature teenaged protagonists. (See, for example, Alison Goodman’s Eon and Eona, which were sold as adult fantasy in every English-language market outside North America.) From one book to the next, from one protagonist to the next, LaFevers makes the stakes increasingly complex on the grand level, and increasingly intimate on the character level, balancing the two masterfully.

While Ismae, the heroine of Grave Mercy, does have a turbulent family backstory, it essentially remains backstory as she is sent from the convent of “Saint Mortain,†one of the Nine Old Golds of Brittany, and plunged into the real-life political intrigues in the court of Anne, the country’s young duchess. (Although, as LaFevers concedes in author’s notes, the historical timeline is increasingly compressed for dramatic effect as the series progresses.) The next novel, Dark Triumph, begins at a climactic moment in its predecessor’s narrative, seen now from the perspective of Ismae’s friend and co-assassin, Sybella. Sybella has also been called upon to defend the duchess, but in doing so she’s forced to return to a family she’s already managed to escape once. I wouldn’t say that her family drama is necessarily darker than Ismae’s, only that she—and we as readers—are forced to confront it more directly, and for a greater duration. That trend continues in Mortal Heart, where Annith, who has sat on the sidelines in frustration during the first two novels, defies the orders of the convent’s abbess and inserts herself into the political conflict… a move that brings secrets even she didn’t know about her personal history to the foreground.

(more…)

5 January 2015 | read this |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.