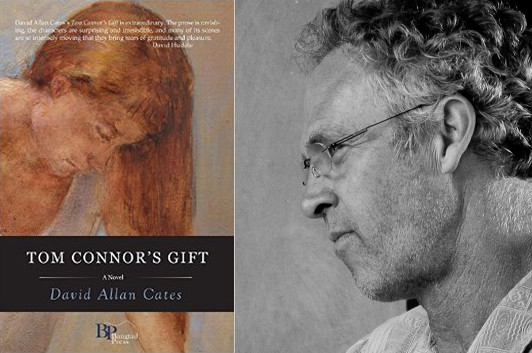

David Allan Cates: An Opera in Prose

When David Allan Cates was ready to start writing the novel that became Tom Connor’s Gift, he took himself to a remote location that wound up giving him more direct inspiration than he’d originally intended… and as the novel’s voices took shape, as he describes it in this essay, they felt as if they had an almost song-like quality.

Five years ago, I arranged to go to a friend’s cabin for a week because my previous novel had been out for a year and I felt pinched and irritated enough, confused, scared and sad enough, not to mention hopeful, grateful and earnest enough to want to start another one.

My three most recently finished novels were stylistically and formally, unconventional. But this time, I thought, driving from Missoula over the mountains toward Great Falls, and then north up the Eastern Front of the Rockies, this time I’m going to write a good old-fashioned love story.

I wanted to tell a long, adventurous and miraculous tale of how two people managed to stay in love over decades. I wanted to write a novel that sounded like somebody you know telling you their long story. I wanted it to be the kind of love story that would make me see things and feel things that I’d never felt or imagined before, and I wanted to write a story that could take the giant swirling storm of middle-aged feelings I’d been having lately—sadness, joy, anger, grief, gratitude—and allow me to spread my arms wide enough to hold them all close. I wanted to feel all there was to feel—all the good and the bad at once, the everything and the nothing at once—and still be able say: Yes Yes Yes! This too is love!

Well. With a goal like that, it’s pretty easy to make excuses not to start. I needed to go away. And I had to come back with something.

I spent the week at my friend’s rustic cabin in the Sun River Canyon. It had an outhouse, and a woodstove, and I hauled water from the lodge up-river. I sat up late outside in the dark and listened to the big fall wind come blasting out of the river canyon onto the Great Plains. I drank wine and smoked cigars and listened to AM radio from Canada. With a headlamp, I re-read a stack of letters I’d gotten from an old friend who’d recently killed himself. The wind made me ecstatic and a little crazy. My thoughts wouldn’t stay in place. Three times a year, I work in Honduras as the coordinator of medical brigades, and I felt the way I always feel when I get back from those trips—like I’ve got new wind in my head, fresh and ecstatic but disorienting. The cabin is on the edge of the Bob Marshall Wilderness, so besides the cigar and wine, I sat up late, always, with bear spray.

I also got up early and wrote, and after a few days I had a chapter—the first chapter of Tom Connor’s Gift. Like me, the narrator was self-exiled in the Sun River canyon. Like me, she had stacks of letters. Unlike me, she’s a woman, a doctor, and recently widowed. And unlike me, instead of just thinking about bears, she actually has one come to visit.

Suddenly I had a start on a story, and it scared me to death—but that’s how I knew I was on to something. Who was she? Who did she love? What was the source of her anger and exile?

All I had on the stage so far was a lone woman in a cabin. No other living characters—besides the bear. But I already understood by that first chapter that this was a story about her love for two men. And so I had two love stories—one story of her first true love and the other with her true lasting love. Not so simple as I’d hoped. Also, I was learning, it was a grief story. A double grief story to match the double love story.

Still, the chapter had real juice. A wounded woman narrator, smart and mean and drunk with grief—way out there on the edge, far from home. Self-exiled. So that couldn’t last forever. I mean, she—like me, at the end of the week—she needed to get home.

What emerged in the novel are two voices—hers, Janine McCarthy, the exiled widowed doctor, grieving her husband’s death, and the voice of Tom Connor, the boy she fell in love with and ran away from home with when she was sixteen. They sing a duet, as Janine’s exile in the cabin is punctuated by re-reading the letters Tom sent her while he roamed around Central America during the bloody 1980s. Tom’s tragic and hopeful vision, while impossible for Janine to fully feel and understand when she was busy building her life with her husband, having children, working as an emergency room doctor, now these many years later find space in her broken self to enter.

This time through the letters, she’s transformed by Tom’s ragged and unflinching display of love and loss and hope and despair. His voice, like Janine’s, is full throated and full-throttled. In this novel, I’d found two characters whose language allowed me to let them rip, let them riff. Neither are coy. They are full-blooded, passionate. In fact, I often thought I was writing songs when I was writing these chapters. They had to sing from the deepest part of the body. They had to come up unfiltered and loud, and rhythmic and tuneful. The novel had turned into a form that allowed two opera singers a stage to sing of everything they loved and everything they’d lost, and to try, in the beauty of the music, to make sense of it all.

So five years ago I thought I’d write a simple, old fashioned love story, but instead, I wrote an opera. Maybe they’re the same thing.

16 December 2014 | guest authors |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.