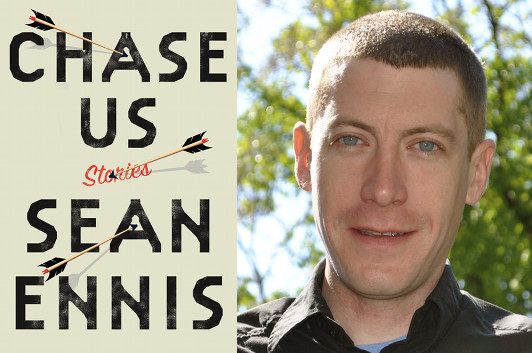

Sean Ennis: An Unsettling “Orientation”

photo: Claire Mischker

The Philadelphia of Sean Ennis’s Chase Us is a surreal, violent territory, one that the narrator navigates precariously from one story to the next. The collection isn’t so much a novel in stories, I think, as a series of variations on a theme; although the setting and the characters carry over from one story to the next, it doesn’t seem—at least initially—that a linear narrative carries over with them.) Once you’ve read a few of Ennis’s stories, you might be able to see what drew him to the Daniel Orozco story he’s written about in this guest essay…

I’ve always liked stories about work. Not only is it the place where most of us spend the majority of our time, but for a fiction writer, it seems like the ideal setting to create drama. Unless you’re very lucky, work is a place where you are often forced to interact with people you’d otherwise avoid.

Daniel Orozco’s “Orientation” takes the form of a dramatic monologue given by a middle manager introducing a new employee to the company. The specific work that this office engages in is never really mentioned, but we quickly get the sense that the audience for this speech has not exactly landed the ideal job.

In a lesser writer’s hands, it is easy to imagine this piece functioning as a one-note gag, riffing on the banal idea that office life is alienating and unfulfilling. No doubt, that idea is in Orozco’s story, but he’s mainly done with it after the first page. Instead, what follows is a list of an increasingly terrifying cast of characters who inhabit this particular office, brutally dissected by the narrator who speaks of the rules of the coffee pool and the sadomasochistic habits of his coworkers with an equally detached tone.

What I love and admire about this story is the way that both form and content are working in tandem. First, form. As a dramatic monologue, it places the reader in the position of the new hire being oriented, evaluating his/her new job for the first time. By the end it leaves the reader with a choice—decide to return for the second day on the job or run away screaming. I’m not suggesting that the story is so immersive that the reader actually forgets where they really stand—this isn’t a Disney ride. But it does mimic the question lots of people have about their job when they leave it for the day: will I come back tomorrow? While most great stories pose a question to the reader on some level, this seems much more explicit.

The structure of the story is also odd. It follows the traditional ideas about plot in only very loose ways. The introduction of characters and conflict/rising action/climax/denouement matrix is hard to apply to the piece. Is the climax when one employee is revealed to be a serial killer? Or is it really after the story is over, when the new employee (us) makes a decision about whether or not to return to work? Is the middle management narrator the main character? Or is it the new employee (us)? Simple questions about the piece are difficult to answer.

The content does what most successful satire does in terms of starting a line of thought and pushing it, snowball-like, to ridiculous ends. By the end of just the third paragraph of the manager’s speech, the threat of being fired has already been introduced:

“That was a good question. Feel free to ask questions. Ask too many questions, however, and you may be let go.”

The other employees in the office are beyond quirky. Anika Bloom’s hand began to bleed during a meeting and, “[she] told Barry Hacker when and how his wife would die. We laughed it off. She was, after all, a new employee. But Barry Hacker’s wife is dead. So unless you want to know exactly when and how you’ll die, never talk to Anika Bloom.” It’s good advice. So is this:

“This is Matthew Payne’s office. He is our Unit Manager, and is door is always closed. We have never seen him, and you will never see him. But he is there. You can be sure of that. He is all around us.”

I teach this story often, in a variety of venues, and the more I do, the more I find myself coming to the conclusion that, rather than being the most terrifying orientation that has ever taken place, it may, in fact, be the most useful. This new employee (us) has been given all the information he/she needs to know about the job before he/she has started it. Every workplace has weirdoes, people who are dangerous, people who need your extra affection, etc. How useful to know it all on the first day!

“Orientation” was originnaly published in the 1990s and might feel a little dated. There is no discussion of email, or video conferencing, or Red Bull, etc. but it’s not hard to imagine how those details might fit into the world of the story. What still resonates, even if the reader has no experience of this sort of specific office life, is the tension between the necessity of being employed and the fundamental strangeness of the set-up. What we give up and tolerate and hopefully excel at to keep the lights on at home.

One final compliment for the piece: as a writer of short fiction myself, I read as much of it as I can. This was one of those rare stories that launched me from bed to my own desk when I finished it, charged with the impulse to get back to work late at night. I read a lot of great stuff, but this doesn’t happen all that often. And I still think about the question the story poses, a question that I think lots of us wrestle with: How bad does a job have to be to turn it down?

8 June 2014 | selling shorts |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.