Life Stories #69: Misty Copeland

Subscribe to Life Stories in iTunes

In this episode of Life Stories, the podcast where I talk to memoir writers about their lives and the art of writing memoir, Misty Copeland, a principal soloist with the American Ballet Theater, talks about Life in Motion, her story of how, in the midst of a chaotic home life in 1990s southern California, she was guided (not altogether willingly at first) into ballet training and discovered a true aptitude for dance. Despite the emotional turbulence of Copeland’s teenage years, as her mother and her ballet mentor fought over their competing visions of what was best for her, she persevered, and has become one of a handful of African-American principal soloists in ABT’s history.

One of the things we discussed was the hurdles that African-American dancers can face in being considered for the iconic roles of classical ballet, and how Copeland has made notable progress on that front, including a starring performance in Stravinsky’s Firebird Suite in 2012. It’s a problem similar to that actors of color deal with when casting directors simply “don’t see them” for characters who are thought of as “white” by default, and Copeland talked about how she worked up the courage to resist being pigeonholed in ways that would keep her out of the great ballerina roles:

“When you’re in a company as large as American Ballet Theater, with eighty dancers… You don’t come into a company as a young dancer and get a shot to do a leading classical role immediately. An easier way to break you into doing leading roles is to go the contemporary route. So that’s where I was pushed immediately, and they saw that I was really good at it, so I felt like I was being put in this position that I didn’t want to get stuck in. I saw myself as a ballerina, always, and it took me years to be able to say to the artistic staff, ‘Remember I’m a ballerina?’ I trained as a classical dancer; I didn’t train in any other form of dance. It took a lot for me to say that, but I’m happy I did.”

Listen to Life Stories #69: Misty Copeland (MP3 file); or download this file by right-clicking (Mac users, option-click). Or subscribe to Life Stories in iTunes, where you can catch up with earlier episodes and be alerted whenever a new one is released. (And if you are an iTunes subscriber, please consider rating and reviewing the podcast!)

8 May 2014 | life stories |

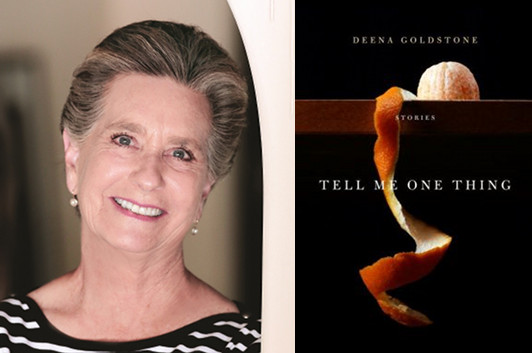

Deena Goldstone on Amy Bloom’s “Sleepwalking”

photo: Patricia Williams

Readers of a certain age (my age and thereabouts, in fact) may recall the TV-movie A Bunny’s Tale, in which Kirstie Alley plays a young Gloria Steinem, going undercover as a server at the Playboy Club. That film was one of the early screenwriting credits of Deena Goldstone, whose debut short story collection, Tell Me One Thing, has just come out. In this guest essay, Goldstone talks about the valuable lesson that one of Amy Bloom’s stories provided as she was making the transition from screenplay to short fiction.

Amy Bloom showed me how to write about grief without ever mentioning the word. Many months before I even contemplated writing my first short story, I read one of hers, “Sleepwalking.” It was in the days when I considered myself a working screenwriter.

I was at the point in my writing life, thirty years in, when I felt I had really mastered my craft—one that is precise and structured and disciplined. But just as I reached that level of confidence, I also began to bump up against the limitations of the form. There’s little place for lyricism in screenwriting or long descriptive paragraphs or internal monologues. Characters’ emotional states have to be inferred from dialogue and behavior. I found myself reading voraciously in other forms—short stories, novels—without quite understanding that I was schooling myself in another way to write.

Amy Bloom became my teacher early on. “Sleepwalking” is about a recent widow, Julia, whose husband, Lionel, a musician, has died of causes we don’t know and never learn. Bloom’s focus is on the small family he has left behind: Julia, his third wife, Lionel, Jr, nineteen, his son from his second marriage, Buster, his young son with Julia, and Julia’s mother-in-law, Ruth. It is a story about how these people get through the raw and painful days right after the funeral.

What stopped me in my tracks when I read the story was how much Bloom can tell us in a single sentence. Here is a description of her difficult mother-in-law and of the man her husband was when she married him—Ruth “hadn’t raised Lionel to be a good husband; she’d raised him to be a warrior, a god, a genius surrounded by courtiers. But I married him anyway, when he was too old to be a warrior, too tired to be a god, and smart enough to know the limits of his talent.â€

And here is the sentence describing the first meeting of Julia and her future stepson: “When my husband brought his son to meet me the first time, I looked into those wary eyes, hope pouring out of them despite himself, and I knew that I had found someone else to love.â€

Now we know everything we need to know about the past—who Lionel was when Julia married him and about the, guarded, hopeful boy she raised and loved as he needed to be loved. Amy Bloom gives us the “backstory,†as we say in screenwriting, in three amazing sentences.

5 May 2014 | selling shorts |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.