Trigger Warnings Will Not Destroy Literature

You might have seen the recent New York Times story about proposals that “trigger warnings,†a popular term for descriptions of potentially disturbing subject matter, be added to college syllabi to alert students before exposing them to such material, often in order to prevent post-traumatic responses. Examples cited in the Times of the sort of subjects that might merit a trigger warning include the anti-Semitism in The Merchant of Venice and the suicide in Mrs. Dalloway; one might also mention, as Jay Caspian Kang did in a later essay arguing against such warnings, Lolita as, in one interpretation, “the systematic rape of a young girl†by a much older man. You can likely come up with some examples from your own reading.

Well, as that article details, there are objections galore to this; some critics have declared trigger warnings an imminent threat to academic discourse, forcing professors to retreat to “safe,†harmless texts (whatever those are supposed to be). One free speech advocate quoted by the Times argues, “It is only going to get harder to teach people that there is a real important and serious value to being offended. Part of that is talking about deadly serious and uncomfortable subjects.â€

The underlying logic in that statement, however, is that the professors are the ones who know best when it’s time to talk about those subjects, and that students should have no other option but to have those conversations on the professors’ terms. If a student doesn’t feel emotionally ready to confront the subject matter, too bad; the experience, this argument proposes, will ultimately be to his or her benefit, no matter how traumatic it feels in the moment.

As a rhetorical position, that’s not entirely unsympathetic. Stepping outside the classroom for a moment, I’m reminded of Sam Fuller’s film Verboten! (1959), set in post-WWII Germany. In one of the film’s pivotal scenes, a German woman takes her teenage brother, who is falling under the sway of neo-Nazis, to the Nuremberg trials, where documentary footage from liberated concentration camps is shown as evidence against the leaders of the Third Reich.

Fuller, who saw firsthand the atrocities at Falkenau, was deliberately confronting American audiences with raw images of the Holocaust, refusing to let them minimize the extent of what happened. “It’s something we should see,†the woman declares when her brother tries to look away. “The whole world should see.â€

But who decides what the whole world should see? And by what criteria?

(more…)

23 May 2014 | theory |

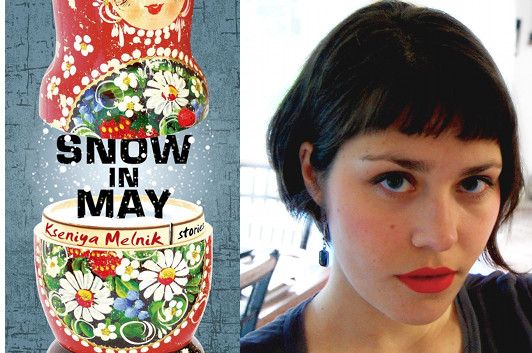

Kseniya Melnik and the Long Short Story

photo via Kseniya Melnik

Kseniya Melnik was born in the northeastern Russian city of Magadan, which also serves as a home base for the characters in the stories that make up Snow in May, her debut collection. Their experiences span late Soviet and post-Soviet history; she jumps back and forth over decades from one to the next, but it’s not jarring, because each story is captivating in its own way, immersing us in an equally compelling interior drama. Another side effect of that immersion is that you won’t notice how long some of these stories are—for, as she explains in this essay, Melnik has learned to give her stories the space they need, and we’re the ones who benefit from it.

Ever since I became serious about writing stories, my drafts have consistently come in at over what is considered the page limit for the standard American short story—twenty-five pages, or about 7,000 words. This seems to be the magic number, at least according to most contest rules, literary journal submission guidelines, syllabi of college creative writing workshops, and MFA application requirements. The stories in The New Yorker mostly adhere to that length or less, and the compact stories of Ernest Hemingway, Raymond Carver, Tobias Wolff, John Updike, and Lorrie Moore still wield great influence around the workshop tables of America.

For many years, I chopped my stories down to bare bones to submit to contests and journals only to see the drafts grow back all that meat (and some descriptive fat) in the next revision. Even in the MFA workshops, where the submission guidelines were expanded to “as long as it needs to be,” my drafts were the longest in the class.

I always turned in my forty-pagers with a plea for help to choose what to cut. Usually, my classmates’ suggestions were superficial—fifty words here, a hundred there. To fit into that key length of twenty-five pages, I would have to re-imagine the scope of the story, cut scenes, whittle down characters. An occasional recommendation was: write a novel out of it! But I was convinced that what I had on my hands were definitely short stories and not summaries of novels or even compressed novellas.

19 May 2014 | selling shorts |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.