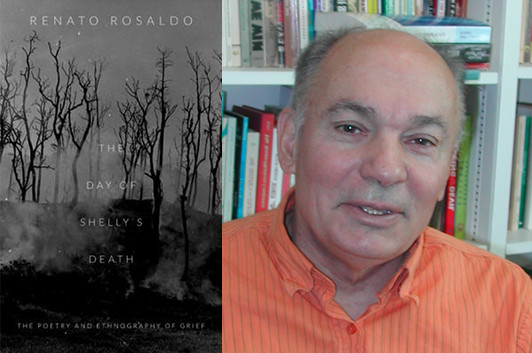

Renato Rosaldo: Poetry in Plain Language

photo via NYU

In The Day of Shelly’s Death, the anthropologist and poet Renato Rosaldo writes about the death of his wife, Michelle Rosaldo, in 1981 just after they had arrived in the Philippines for a fieldwork expedition. As he addresses the subject from various perspectives—including, in “New Shoes,” that of Shelly herself—Rosaldo maintains a plain, straightforward tone… and, in this guest essay, he discusses another case in which a moment of poetic insight was couched in simple language. Is Naomi Shihab Nye’s “Gate A-4” a poem, a very short essay, or something else? Rosaldo sides on the case of poetry, and I’m inclined to agree.

I work hard to write accessible poems. It’s difficult to make it look easy.

In writing to be understood I’ve sometimes been inspired by what William Butler Yeats, in his poem “Adam’s Curse,” famously said.

“A line will take us hours maybe;

Yet if it does not seem a moment’s thought,

Our stitching and unstitching has been naught.”In other words, he worked and worked to write lines of poetry that sing with meter and rhyme, yet read as if they were effortlessly dashed off without a moment’s thought.

Nonetheless, I’ve found that readers often worry that a poem they can understand is artless, perhaps prose, merely a good story, not a poem. That readers can be so disconcerted by an accessible poem makes one wonder. Do they think poems are beautiful words that can’t be understood? What comes to mind for me is what a student said about my lectures in the first course I taught. “Your lectures,” she said, “are pure poetry—beautiful, I can’t understand a word.”

Consider, for example, an accessible poem by Naomi Shihab Nye, “Gate A-4,” that recently went viral on the internet. Although they were carefully crafted, her verses appear chatty, conversational, as if casually told to a friend. Readers posted comments. They agreed, her verse was beautiful, but some wondered: Was it poetry? Prose? Or just a good story?

The speaker of the poem (from now on I’ll call her Nye for short) began by saying

“After learning my flight was detained 4 hours, I heard the announcement: If anyone in the vicinity of gate A-4 understands any Arabic, please come to the gate immediately.”

The scene was initially set in the mundane—delayed flight, though four hours is more than usual. Then an announcement in an ominous key: An Arabic speaker urgently needed. Why the urgency? Terrorism? A profiled passenger in handcuffs requiring interrogation? In her succinct, understated, matter-of-fact way, Nye has artfully built dramatic suspense.

Nye said, “Well—one pauses these days.” Indeed…

She then went to her gate, which turned out to be A-4. Once there, she found “an older woman in full traditional Palestinian embroidered dress, just like my grandma wore, was crumpled to the floor, wailing loudly.” A distressed and baffled flight service person pleaded with Nye for help. No sooner did they announce the flight was delayed, she said, than the old woman collapsed into wailing. The mystery in Nye’s subtle mini-drama has grown.

The central subject of the poem seamlessly shifted to language as Nye spoke with the old woman in her halting, second-generation Arabic. “Shu-dow-a, Shu-bid-uck Habibti? Stani schway, Min fadlick, Shu-bit-se-wee?” These words, even if accented, were familiar to the old woman who grew calm and stopped crying. In talking with the old woman Nye learned that there was a linguistic breakdown. The old woman (mis)understood that the flight was cancelled, not delayed. It would be catastrophic for her. She would have to miss her appointment the next day for a necessary medical procedure. Nye phoned the old woman’s son who was to pick her up at the airport. They spoke English. Nye then phoned the old woman’s other sons. Other calls followed—for fun, in Arabic—to Nye’s father and a few Palestinian poets. Healed by conversing in her native language, the old woman began laughing and chattering.

Then a homespun epiphany. The old woman “pulled a sack of homemade mamool cookies—little powdered sugar crumbly mounds stuffed with dates and nuts—out of her bag and was offering them to all the women at the gate.” Nobody refused: “It was like a sacrament.” All the women were covered with powdered sugar. Nye said, “There are no better cookies.”

The airline joined the ritual process and servers, also sugar covered, poured apple juice and lemonade for all. By now Nye was holding hands with her elder and said, “This is the world I want to live in. The shared world.”

16 March 2014 | poets on poets |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.