Anthony Varallo: A Sense of Speech

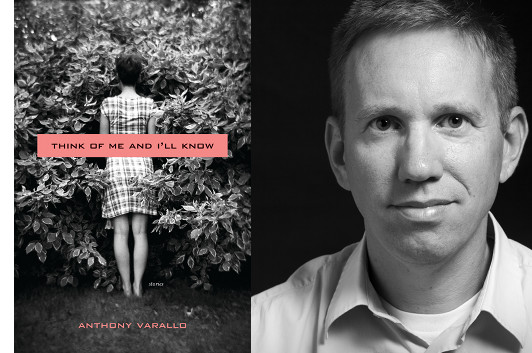

I was introduced to the stories of Anthony Varallo in 2006, after he’d won the Iowa Short Fiction prize and contributed a guest essay to this site celebrating a favorite Cheever story. I was delighted to hear from him recently and to hear about his latest story collection, Think of Me and I’ll Know, which I’m very much looking forward to reading. I invited him to write about another story he loved, and he responded with this tribute to the innovative dialogue of V.S Pritchett.

If I had to pick one short story writer as the most neglected, least read, or simply overlooked, it would probably be V. S. Pritchett. Pritchett is, to my mind, the greatest British short story writer of all time, and his Complete Collected Stories was a revelation to me when I first read it years ago, and continues to be a book I go back to time and time again, especially when I’m thinking about dialogue. Pritchett was a master of dialogue.

One of Pritchett’s best stories, “A Sense of Humor,†begins with an exchange between the narrator, a traveling salesman checking into a new hotel, and the attractive woman who works at the hotel desk. Here’s how Pritchett conveys their first meeting:

“You’re a stranger here, aren’t you?†she said.

“I am,†I said. “And so are you.â€

“How do you know that?”

“Obvious,†I said. “Way you speak.â€

“Let’s have a light,†she said.

“So’s I can see you,†I said.

I can still remember the charge I felt the first time I read those lines, which start off as a dull exchange of commonplaces between two strangers, until Pritchett, in the second line, has the narrator say, “And so are you,†a flirtation that the woman accepts three lines later with her line, “Let’s have a light,†although Pritchett never says she’s accepted anything. Instead, he has the narrator raise the stakes with his next line, “So’s I can see you,†signaling to the reader that the narrator understands the woman has agreed to his advance; he may now advance further.

This exchange not only contains the DNA of the story that is to follow (the two of them begin a relationship); it also showed me a whole new way to write dialogue: you could take significant leaps between one line and the next—the characters didn’t need to have a strict Q&A session—all to intensify the impact of the lines that remained. Only the highlights mattered, not the play by play.

Later in the story, the narrator brings the woman home to meet his parents. In a moment I’ve read and re-read again and again, the narrator’s father, an undertaker, laments the disappointing changes in the undertaker business:

“The whole business has changed so that you wouldn’t know it, in my lifetime,†said my father. “Silver fittings have gone clean out. Everyone wants simplicity nowadays. Restraint. Dignity,†my father said.

“The war,†he said.

“You couldn’t get the wood,†he said.

“Take ordinary mahogany, just an ordinary piece of mahogany. Or teak,†he said. “Take teak. Or walnut.â€The first time I read those lines, I wondered if my edition had a printing error: why were the father’s lines—’all from a single speaker—occasionally spaced as if they were from multiple speakers, with a new line for each new speech? That was incorrect, wasn’t it? The father’s speeches could have just as easily been condensed into a single paragraph, couldn’t they? I’d never seen another writer stack the lines one after the other, club-sandwich style, as Pritchett had; I still haven’t seen another writer do that. The result is that the father’s lines hit with added force, carrying not only the weight of his speech, but the pauses between those speeches. I didn’t know such a thing was permissible or possible.

In the closing lines of the story, the narrator and the woman ride together in a funeral procession, observing the people looking in at them:

“They’re raising their hats,†she said.

“Not all of them,†I said.

She squeezed my hand and I had to keep her from jumping about like a child on the seat as we went through.

“There they go.â€

“Boys always do,†I said.

“And another.â€These lines work like a pointillist painting: brightly lit portions of conversation that create an impression of the whole event. I read those lines and was hooked. And then I read the story a second time, a third and a fourth and more, wishing I could write dialogue like that, too.

4 December 2013 | selling shorts |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.