Life Stories #52: Ann Mah & Anya von Bremzen

Subscribe to Life Stories in iTunes

photos: Katia Grimmer-Laversanne (Mah); John von Pamer (von Bremzen)

This episode of Life Stories brings together two women whose food-inflected memoirs took their titles from the same Julia Child classic: Ann Mah writes about her excursions to find the great regional dishes of France in Mastering the Art of French Eating, while Anya von Bremzen combines the history of her family in the Soviet Union with an exploration of the complex interplay between the party line on Soviet cuisine and the realities of what people ate in Mastering the Art of Soviet Cooking.

Two very different projects—but as you’ll learn over the course of our conversation, Mah and von Bremzen do share some common ground, from their mutual backgrounds in travel and food journalism to the roles that family and memory play in each of their stories. And, perhaps most importantly, the realization that a great dish isn’t necessarily defined by its ingredients, but by the experience of preparing and enjoying it with others. (You’ll also learn about the distinctive aroma of andouillette, and the favorite dish of Joseph Stalin… both of which, I have to confess, sounded delicious!)

Listen to Life Stories #52: Ann Mah & Anya von Bremzen (MP3 file); or download this file by right-clicking (Mac users, option-click). Or subscribe to Life Stories in iTunes, where you can catch up with earlier episodes and be alerted whenever a new one is released. (And if you are an iTunes subscriber, please consider rating and reviewing the podcast!)

11 November 2013 | life stories |

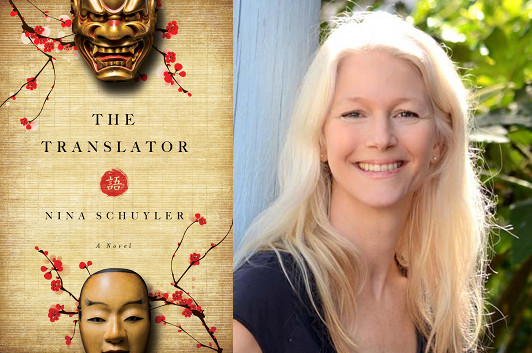

Nina Schuyler Has Translation on the Brain

photo: Cristina Taccone

As Nina Schuyler explains below, the protagonist of her new novel, The Translator, thinks she understands the Japanese novel she’s rendering into English, but she may be looking at it from a skewed perspective. What happens when the rest of her life is thrown into disarray by a brain trauma that takes away her ability to speak English—but leaves her fluent in Japanese? That would be telling, of course… but I can share Schuyler’s insights into what drew her, as a novelist, to this captivating premise.

In 2005, The New Yorker published an article by David Remnick, “The Translation Wars,” about a married couple that was busy re-translating all the great Russian novels into English: Richard Pevear, an English speaker, and his wife, Larissa Volokhonsky, a Russian émigrée. Finally, what Nabokov called a “complete disaster” and “the dry shit” of Constance Garnett, who had first translated Russian literature into English, could be set aside.

What caught my eye wasn’t the word “Translation” in the title of the article, but the words “Tolstoy” and “Dostoyevsky” in the subtitle. As a girl, I fell in love with Dostoyevsky, Tolstoy, Chekhov, and Pasternak. I remember one summer when I was twelve, I carried Doctor Zhivago every day to the pool. Back then, I didn’t even consider that the stories were first written in Russian—what Thomas Mann called “the muddy, barbaric, boneless tongue from the East.” What I thought about was snow, sleigh rides, passion, betrayal, revolution, peasants, czars, love.

Constance Garnett was, in fact, English. In 1891, when she had a difficult pregnancy, she taught herself Russian. Soon she began translating. According to Remnick, when she came across a word or phrase she didn’t know, she merrily skipped it and moved on. She was not skilled enough to carry forth certain verbal motifs and complicated sentences.

I went to my bookshelf. My Russian literature—all Garnett’s translations! Watered down, corrupted translation, soaked in a heavy dose of English custom and sensibility. As all writers learn, conflict makes for story. The New Yorker article presented itself to me as a seed for a story: What if a translator thinks she did a superior job, as Garnett most likely did, but, in fact, mangled the job?

11 November 2013 | guest authors |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.