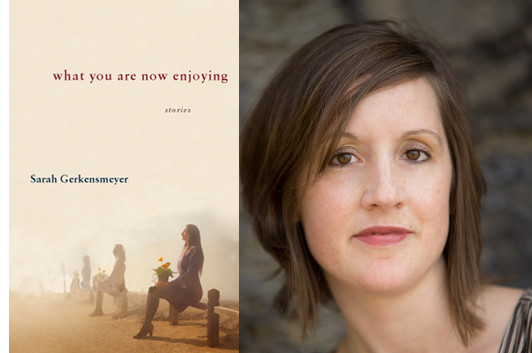

The Images That Stick with Sarah Gerkensmeyer

photo: L. Deemer

Many of the stories in Sarah Gerkensmeyer‘s What You Are Now Enjoying, like “Dear John,” unfold with a dreamlike logic; even a story like “My Husband’s House,” which seems relatively grounded, has a hallucinatory quality to it—we wander through in a bit of a daze, much like her protagonists. Yet the “surreal slant” in her fiction “has been somewhat of a mystery for me,” she told an interviewer; maybe, as she theorized, it has something to do with her midwestern routes: “There is magic and mystery there. Something like heat lightning, I guess. Or crouching beneath a utility sink in the basement while a tornado roars by like a train. There is a sense of the unexpected creeping up out of the familiar and the ordinary and the mundane. I think I try to encapsulate that same aesthetic in my own work.” And, as you’ll see, when she finds examples of that aesthetic in other people’s stories, it stays with her.

New Yorkers will be able to see for themselves when Gerkensmeyer comes to read at Pen Parentis on April 9, 2013.

In a red river: a small child drowning, tugged below the surface by a swift current—a piggish man in pursuit.

On a train: a mother righting her baby daughter in her seat after she’s toppled over—a white-haired stranger with a cigar hovering above them, grinning.

In a restaurant in Moscow: a starving boy pulled in from the street and offered oysters—the salty, slimy crunch when he bites into the shell.

It’s the images that haunt me most. The red water and the piggish man in Flannery O’Connor’s “The River;” the toppled-over baby in Shirley Jackson’s “The Witch;” the moldy crunch of teeth against oyster shell in Anton Chekhov’s “Oysters.” And when I come back to these stories years later and come face-to-face with the exact, horrible context of each of them once again, the bigger picture is haunting, too, of course.

In “The River,” a little boy who has sudden, skewed ideas about religion drowns as he tries desperately to baptize himself. In “The Witch,” a stranger on a train tells a young boy a horribly inappropriate story about how he also had a little baby sister and he strangled her and chopped her up into pieces. In “Oysters,” a starving boy with a sick father is pulled off of the streets of Moscow and into a fancy restaurant, where he is offered oysters as a joke.) But that’s the whole story, something I usually forget relatively soon after I’ve set a book down. It’s the images I carry with me. It’s the images, I think, that push me to write my own stories.

A few years ago, I was relieved to come across an article in The New York Times Book Review called “The Plot Escapes Me.” The writer James Collins asks, “Why read books if we can’t remember what’s in them?” I read that sentence and thought: Okay. Good. I’m not alone.

He goes on to tackle the neuroscience of reading—how the transient pleasure of the experience is taken over by a kind of “mental radiation.” When we read a good story, new pathways are created in our brains. Even the stuff we’ve long forgotten is still there, tucked deep within the folds of our subconscious, each drawer sliding open when we need it.

The novelist Paul Scott argues that a novel is a “sequence of images.” In good fiction, “the images come first,” and then it is up to the writer to make a shape and a sense out of them. Charles Baxter (via Gerard Manley Hopkins) talks about the power of the “widowed image,” that vision that sticks with the reader even when everything else from a story has faded. And so I breathe a deep sigh of relief to know that my forgetfulness when it comes to reading fiction is not a fault that I must hide and deny. As long as I’m haunted by at least a single, piercing image after I’ve set the book down, then both the writer and myself, the reader, have done something right. All of the stories I’ve read are with me still, swirling around and colliding within my subconscious in a mad collage of images—red rivers, toppled-over-babies, salty oyster shells, a little green bicycle, a watery potato soup, burned hands bandaged in bright white, the sting of chlorine.. As I write this, I remember the context for some of those images, but not all of them.

My four-year-old and I have started reading chapter books at bedtime. The pictures are starting to disappear from his books. In order to see the things in the stories, he has to use his imagination. While reading to him, sometimes I glance at him and watch as a single image sinks in and settles behind his eyes. Sometimes he looks a bit anxious as he listens, as if he’s worried that this incredible thing will eventually slip away. Maybe soon I’ll tell him not to worry, that all of those pictures will stay with him forever. I’ll explain it all as best I can—the neuroscience of forgetting and of never letting go.

20 March 2013 | selling shorts |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.