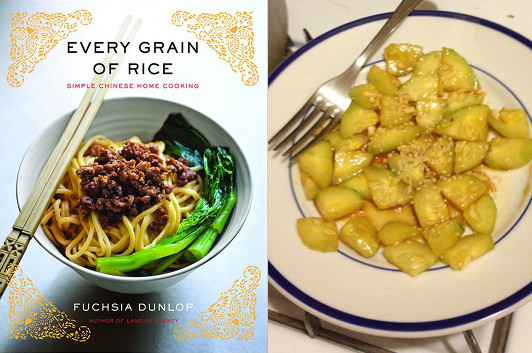

Fuchsia Dunlop’s Smacked Cucumbers in Garlicky Sauce

I’ve been experimenting with a new cookbook recently, Fuchsia Dunlop’s Every Grain of Rice, which follows through on its promise of “simple Chinese home cooking” with some fantastic dishes. My favorite so far, in part because it’s ridiculously easy to make, is a salad of “smacked cucumbers” in a combination of soy sauce, brown rice vinegar, and chili oil with a little bit of sugar and some finely chopped garlic. It only takes about ten minutes to make, and that’s mostly because you’re waiting for the salt you through on the cucumber to draw out some water. (I’ve had to adjust Dunlop’s formula, though—halving the amount of chili oil and bumping up the vinegar a touch—because otherwise my mouth would be on fire.) Put this next to a plate of rice, and it’s pretty much a fantastic light dinner on its own.

I had the pleasure of meeting Fuchsia Dunlop when she was in New York City recently to promote the book, after I’d just reread her memoir, Shark’s Fin and Sichuan Pepper, where she writes about falling in love with Chinese cuisine as a student in Chengdu in the mid-1990s, a pre-Internet era when being halfway around the world really did effectively cut you off from your old surroundings. Soon, she was setting aside the journalism career she’d begun to establish—and which had in its way brought her to China—in order to study cooking and write about what she was learning. “I always wanted to do something about food, though,” she said. “If I hadn’t been an academic, I have no doubt I’d have gone to work in a restaurant at 16.”

25 February 2013 | cooking |

Susan Sherman: Peddling for Gold

The early 20th-century Ukraine, still known in those days as “Little Russia,” is a world away from the Disney Channel’s That’s So Raven, so I was curious about what brought that show’s co-creator, Susan Sherman, to the story of Berta, a young Jewish woman who gets a taste of Moscow high life and then is sent back home to her family in Mosny. It turns out The Little Russian is rooted in Sherman’s family history—and though she knew that history well as it had been passed down among her kin, she soon realized that’s not the same thing as a story you can tell in a novel. Fortunately, she explains, there was one aspect of the novel’s emotional core she didn’t have to research, because she’d gone through similar experiences in her own life…

I remember the morning I lay in bed thinking about writing a Russian novel. It was a cold, bright winter morning and I had just finished my last season on That’s So Raven. I couldn’t imagine doing another season in television; after a decade, I was burned out. Sitcoms are a tough life for a writer: the hours are grueling and the work isn’t very satisfying. I wanted to write something I cared about, to be challenged. It was time to write my grandmother’s story.

For as long as I can remember the Grandma Bessie story was the legend of our family. No other story in our family could compare. It was filled with pathos, courage, and heart-stopping action. Grandma Bessie, née Berta Alshonsky, was born in a little shtetl (that’s Yiddish for Jewish hamlet) on the Dneiper River in the Ukraine and was sent to live with rich relatives in Moscow when she was fourteen. At twenty-two, she was sent back to the shtetl, where she met and eventually married my grandfather, a successful wheat merchant. Together they built a comfortable life in Cherkast until he got drafted into the Czar’s army, contracted pleurisy, and, after recovering, fled to America to avoid serving out his time. Grandma Bessie’s fatal mistake was not going with him.

She planned to join him once he got settled, but this was January 1914. By August of that year World War I broke out and she found herself trapped in the Ukraine with her two children. Over time she lost everything and was reduced to peddling to keep her children from starving to death. Everyday she would go out to the countryside and peddle cheap beads, gold jewelry, pots and pans, anything that could turn a profit and keep food on the table. It was a hard life slogging through the muddy fields, dodging the warring factions, and selling or trading her wares to keep her children alive.

20 February 2013 | guest authors |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.