Think Before You Answer Your Critics

I recently attended a conference that Digital Book World put on about “discoverability and marketing” for the publishing industry, where one of the speakers was novelist Elle Lothlorien, who was there to discuss her belief that authors should respond to negative online reviews. For Lothlorien, who comes at this with the philosophy that a writer is also a businessperson and a reader is also a customer, this is simply attentive customer service. As she would later explain:

1) You are not responding to negative reader reviews in order to get the reader to alter their review in any way.

2) You are responding to negative reader reviews in order to neutralize the negative feeling the customer has about Business You (often known as “the authorâ€) and Your Product (better known as “your bookâ€).

Lothlorien’s specific advice for authors when they choose to engage people who’ve reviewed their books negatively online includes several sensible guidelines about how to conduct yourself graciously and succinctly—listening, acknowledging, and moving on. It’s a great contrast to the bullying tactics of some insecure authors who actively seek to shame and harass critics on even the least possible slight. It also dovetails neatly with the recent discussions in literary circles about whether critics need to be more critical and what happens when criticism turns ugly.

I thought about her advice earlier this week, when an author took it upon himself to respond to my wife’s criticism of one of his books.

Mrs. Beatrice (which is what I call her in these pages, to protect her privacy) is in a monthly book club; last year, they read a book that totally did not work for her, and she explained why in exacting detail over at Goodreads. There was a solid concept for a book somewhere in there, she thought, but the author did a terrible job of executing that concept.

(I’m not going to tell you who the author is, or what the book is, either, because I want to focus on the underlying principles, not the gossipy bits. I’ll also be paraphrasing as much as possible, and I’d even ask you to refrain from trying to find the answers on Google; again, the point isn’t for you to identify all the players, or to put this author on the spot, but to think about the dynamics involved.)

7 October 2012 | theory |

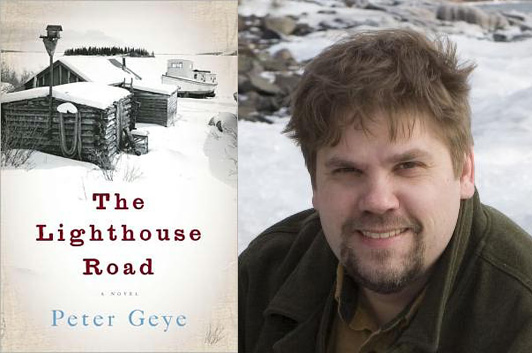

Peter Geye Builds a Patio

Photo: Jeff Fifield

The Lighthouse Road, the second novel by Peter Geye, opens strong, with a woman making her way through a late 19th-century blizzard to give birth to her son, then jumps forward 20-some years for another vivid scene where that young man struggles to negotiate a skiff full of bootleg whiskey across a lake in the dead of night—and continues to cross back and forth as the story unfolds. I could give you a clever architecture metaphor for this, but the fact is, Geye’s already got one way better than anything I could come up with, and he shares it in this guest essay about a non-literary activity that turns in a moving description of an experience anyone who’s ever embarked on a big creative project will recognize.

There is, I assure you, more than one way to lay a patio.

This spring, after suffering through a home remodeling project that had consumed our lives for the better part of nine months, I decided to undertake the culminating job of laying the patio in the backyard myself. My wife didn’t like the idea. Not at all.

But I wanted a share of satisfaction in the completed project. I wanted to sweat and wear holes in leather gloves. I wanted to hoist six pallets of bricks from one side of my yard to the other. I wanted to finish laying the patio, crack a cold beer, and sit on that patio, admiring my work. After all, I’d just spent those same nine months finishing my second novel. I was ready to get off my ass. Ready for a new kind of tired. And I was ready, frankly, to find a distraction from the anxiety that came with the inexplicably sudden realization that the new book was out of my hands, and would soon be in the hands of readers. I can’t say if this anxiety greets other authors as they take their hands off their work, but it hit me, well, like a ton of bricks.

I’d taken chances in The Lighthouse Road that I’d not had the courage to in my first novel. I’d ventured into a woman’s point of view. I’d added more than a hundred years of history between my characters and myself. I’d taken on subjects that required serious and difficult research and wrote about topics that scared the hell out of me. I tried to write with a new voice. And I’d told the story in an entirely nonlinear way. As is so often the case in my writing life, these decisions were more happy accidents than deliberate decisions. Which only seemed to make the book more difficult to live with once it was out of my hands. My insecurities were roiling up like a stormy Lake Superior.

So, I grabbed shovel and started digging a hole.

4 October 2012 | guest authors |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.