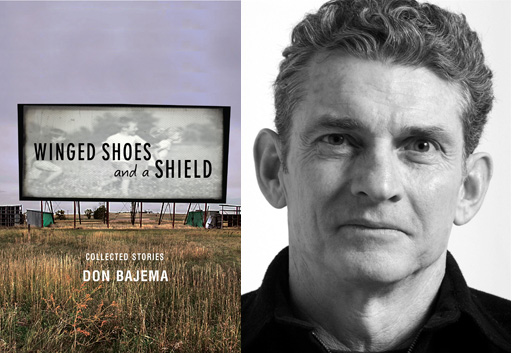

Don Bajema Slips Back into the Twilight Zone

photo courtesy City Lights

When I received Don Bajema’s collected short stories, Winged Shoes and a Shield, I knew I wanted to have him as a guest author here at Beatrice. Usually, for short story writers, that means talking about a particular short story that’s meaningful or influential to them—but Bajema had another idea about the stories that molded his imagination. He makes a powerful point; as someone who’s only ever experienced The Twilight Zone in reruns, and these days primarily in nostalgic “marathon” showings, it can be challenging for me to remember just how challenging and provocative the best episodes were when they first aired. Don Bajema helps me (and maybe you!) remember.

Being asked to speak to a major literary inspiration or influence increases my heart rate at the prospect of leaving so many out. So I’ll look back to the seminal influences and skip many breath-taking works and those many moments I’ve gazed up from the page with admiration.

Reading Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn as a third grader inspired me to walk barefoot to school along deer trails in San Diego imagining steamboats rounding canyon walls in the hope I was escaping the effects of civilization. For months, all black asphalt was a slow running river, cars were boats afloat and my sole purpose was to escape school, avoid work, formulate adventures, and stay outside after dark. As the Mississippi ran through Southern California I did my utmost to live up to the code of boyhood Huck had bequeathed us.

Then came a thirty-minute television program on a weeknight, was it Thursday? Or maybe we were so enthralled with the show that a Friday night viewing would stretch through the weekend into Monday morning and guarantee generating a chattering all-at-once conversation by asking, “Oooo, did you see The Twilight Zone?”

Delicious subversion! Mind-bending premises, twists of fate, comeuppance and lessons begging for debate embedded into the outcomes. Everyone knows the Burgess Meredith tragedy. Standing in the rubble of a post-nuclear storm—the bleak set design taken from photographs of Hiroshima or Nagasaki—poor Burgess amid a sea of books wanting only to read, his thick glasses shattered by his own footstep crying, “It’s not fair, it’s not… fair. It’s just not… fair.” We were, ourselves, in the days of duck and cover drills, and every Tuesday noon the sirens wailed from sea to shining sea. Americans from cityscapes to suburbs were supposed to remember the locale of the nearest bomb shelter.

I hope that by citing a network television show as literary influence I’m not making myself appear pedestrian, uninspired and unimaginative.

In my defense, theater is a literary art first, and The Twilight Zone was nothing if not theater transported to television. And Rod Serling was quite the poet-host (…that’s the sign post up ahead…”) Cigarette unfurling a wispy flag, his cool narrow-lapeled black suit, the bemused smile, a hipster Johnny Appleseed sowing ideas that called into question the challenges of the era. This included the repressions and fears of Cold-War America, so weighed down with racism, sexism, war worship, compulsions of conformity and its neurotic embrace of stasis and a militaristic stability: the Missile Gap, Iron Curtain, Cuban Missile Crisis.

Space aliens conquered us through the mere presentation of themselves, trusting accurately that our panic and mistrust would lead us to destroy ourselves. Crashed spaceships on asteroids were in fact in the outer reaches of no more distance than Las Vegas. There were worlds where beauty was considered ugly and what seemed to us ugly was regarded as beautiful. Greed and cowardice were punished.

Modern American fables laid out to an audience accustomed to sing-alongs to the corniest of pop tunes, variety shows of slapstick idiocy, situation comedies riding the momentum of “canned laughter” horse operas, gunslingers.

But The Twilight Zone and its far-reaching themes, its controversy, its provocation inspired, influenced and contributed to the way I and my generation thought. Seeds from Serling soon surfaced in the streets, demanding equality as propped-up authority put on the riot mask, yanked out the fire hose, swung the clubs at the church kids, buried civil rights workers in swampy dams, and in a few months fulfilled James Baldwin’s incredibly prescient book The Fire Next Time. Serling’s seeds also helped make a war untenable to kids who once ate Oreos and drank their milk staring at the spinning cone, the eyeball in space, the astronaut, Dali’s giant scissors and heard a small smiling man in suit—who was in fact a decorated ex-Marine combat veteran from the Pacific theater—speaking to us eye to eye through the fourth wall. Until a few years later, an in-common permission based partly on ideas direct from The Twilight Zone helped to make it entirely reasonable to a whole generation, for a moment, to refuse to fight, refuse to hate, and refuse to obey.

2 October 2012 | guest authors |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.