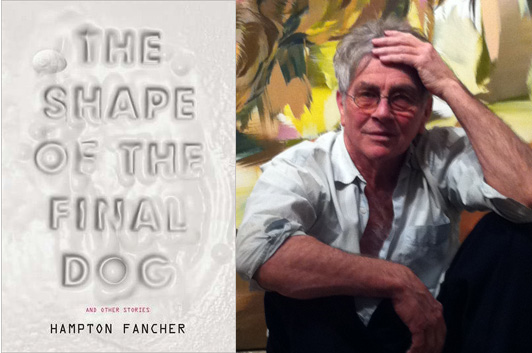

Hampton Fancher Returns to “The South”

photo: Mario Grigorov

There’s a line in one of Hampton Fancher’s short stories where he mentions the surrealist painter Giorgio di Chirico, and though it’s not meant to be a summation of The Shape of the Final Dog, it is just the same—that feeling you get of individually “real” objects that have been arranged together in a dream-like environment, interacting in unexpected and unpredictable ways. In Fancher’s worlds, a frustrated painter creates an opportunity for a young boy to meet his idol, a crippled talking crab, or a gonzo journalist can score an airborne interview with (a very dead) Howard Hughes, and if you want to read the title story as a funhouse version of themes from Fancher’s most famous screenplay, Blade Runner, I think that’s entirely within the realm of possibility…

A great short story happened to me the first time in the 1960s. It was just a few pages by Harlan Ellison called “I Have No Mouth and I Must Scream.” The guy who turned me on to it was missing three fingers. I remember that story, it never leaves and it keeps coming out.

Then there was a Bradbury called “In A Season of Cold Weather.” Something happened to the old man in that story that neither of us will ever forget.

But I love Paul Bowles, too—those stories of people turning into snakes and crabs, screaming at the moon—”By The Water” is right down the rabbit hole. And Charles Bukowski, those three-to-four pagers with unexpected last lines, come down on your head like a rubber hammer. And “Bullet in the Brain” by Tobias Wolff—so smart and full of heart it’s blinding. And the honest, soul wrenching beauty of Alice Munro. And the smart gleam of mean extreams of Roald Dahl like in “Taste.”

But one that got me way back and never lets go, which became a variation in almost everything I ever wrote, is a story by Borges called “The South.” Loneliness, sickness and the absurdity of self regard, the perverse courage of dignity. Tell Robinson Crusoe no man is an island. Starts with arrival, ends with departure—or the other way around. Three little pages. Inertia sustained by spirits and dreams, obssessions. The promise of a place that protects, which will exact the ultimate price. That which sustains will kill you. A lullaby in a vortex. The lewd spitful scuffle between apathy and aspiration.

An accident packed in ice that waits when warmth is what you need. The dream of a lake in a drowning man. The ironic splendors of mortality. (See also: “Appointment at Samara.”) A little ball of bread thrown across the room can end your life. And what you thought was the cornerstone of salvation will crush you. Like the end of “The Stranger,” no hope, but no fear and death becomes exoneration.

11 September 2012 | selling shorts |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.