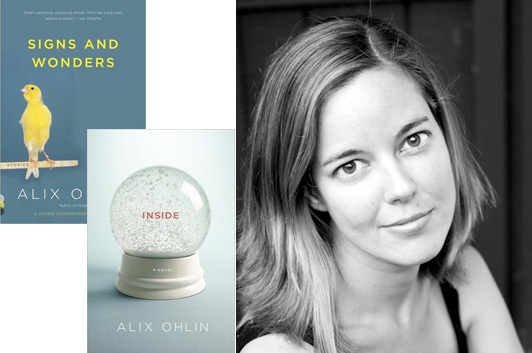

Read This: Inside and Signs and Wonders

Emma Dodge Hanson

In the summer of 2007, Alix Ohlin wrote a “Selling Shorts” essay for Beatrice, which I mention up front as an acknowledgment that I have subjective reasons for being predisposed to like Ohlin’s fiction. And yet, even though I’d known since early in 2012 that Ohlin was simultaneously publishing a new short story collection, Signs and Wonders, and a new novel, Inside, this summer, I hadn’t cracked either one of them open—with all the other books that I’d taken on a professional obligation to read, they’d gravitated to the stack I set aside for, among other occasions, plane and train rides when I finally have a stretch of time in which to read for undistracted pleasure.

They moved to the top of my must-read pile after I read the New York Times hatchet job on Ohlin, which is not so much a book review as an opportunity for William Giraldi to share his pretentious theories on What Makes for Beautiful Prose Stylings with a large audience. How pretentious? The man namechecks Thoreau and Pound in his opening lines:

“There are two species of novelist: one writes as if the world is a known locale that requires dutiful reporting, the other as if the world has yet to be made. The former enjoys the complacency of the au courant and the lassitude of at-hand language, while the latter believes with Thoreau that ‘this world is but canvas to our imaginations,’ that the only worthy assertion of imagination occurs by way of linguistic originality wed to intellect and emotional verity. You close Don Quixote and Tristram Shandy, Middlemarch and Augie March, and the cosmos takes on a coruscated import it rather lacked before, an ‘eternal and irrepressible freshness,’ in Pound’s apt phrase. His definition of literature is among the best we have: ‘Language charged with meaning.’ How charged was the last novel you read?”

“Emotional verity”? “Coruscated import”? “The lassitude of at-hand language”? Somebody’s clearly getting a lot out of his word-a-day calendars! But let’s revisit those first few words: “There are two species of novelist…” Take away the high-falutin’ vocabulary, and you know what you’ve got? You’ve got a “There’s two types of writers” lead, and anybody who’s going to open with “There’s two types of [anything]” should probably just shut the hell up about “the lassitude of at-hand language.”

Nevertheless, Giraldi continues in this vein, attacking everything about Ohlin’s books up to and including their titles; Inside, for example, is “a forgettable moniker that suggests everything and so means nothing.” Mostly, he’s bothered by what he sees as “an appalling lack of register” in her prose, “language that limps onto the page proudly indifferent to pitch or vigor.” He tosses out plenty of examples, and then adds a curious closing paragraph about the “recent parley, in these pages and elsewhere, about ‘women’s fiction’ and the phallic shadow it has been condemned to live in.” He appears bringing this up expressly to ward off the suggestion that there might be any misogynist angle to his evisceration of Ohlin and “her leaden obsession with pregnancy, dating and divorce.” We’re no anti-feminists here at the Times, the logic runs, we just love the English language, and believe in “the writer’s ‘moral obligation to be intelligent’—in John Erskine’s immortal coinage.” (Note the continued namechecking, along with the “immortal coinage;” as Ezra Pound might say, “Way to keep it new, dude!”)

As you read the full review—and even if you don’t—it’s useful to keep in mind a batch of self-reflective essays the NYTBR ran in early 2011 about the state of literary criticism, particularly Stephen Burn’s assertion that critics “who like to issue dogmatic rulings… and to chastise writers… merely add to the noise of culture” and Pankaj Mishra’s warning of a strain in literature and literary criticism that perpetuates “a self-contained realm of elegant consumption.” Countering those viewpoints, though, Katie Roiphe insists “the secret function of the critic today is to write beautifully, and in so doing protect beautiful writing,” and it would certainly seem as if Giraldi falls into that camp—and, based on his opening statement, believes the not-so-secret function of the novelist is to generate the beautiful writing critics will protect.

I described Roiphe’s agenda as “a potential dead-end for serious criticism” when it first appeared, and I stand by that assessment—today, I’ll add that Giraldi shows us a particularly clear example of how self-absorbed the pursuit of “beautiful writing” for its own sake, “the only worthy assertion of imagination,” can become. (I’m only talking about this particular review; I’ll leave it to readers with heartier stomachs to tackle his novel about a man trying to win back the woman who dumped him, clearly a much loftier theme than pregnancy, dating or divorce.)

The scathing attack is especially noteworthy coming so soon after lamentations from other book critics that literary culture is just too nice; if this type of arrogant chest-beating is what they think passes for excellent criticism, they can have their literary culture. J. Robert Lennon has written an elegant takedown of Giraldi’s style, drawing upon negative reviews that he’s written to explain how it ought to be done, and I don’t really have anything to add to it.

“But, Ron,” you say, “are you going to tell us why we should read Alix Ohlin’s new books?”

OK, obviously I didn’t have time to read an entire short story collection and a novel in less than a day. But, prompted by an instinctive reaction against Giraldi’s takedown—as noted above, I’m enough of a fan of Ohlin’s to have invited her to contribute an essay here—I found my copies of the books and started checking out random stories from Signs and Wonders. Here’s what I can tell you: The characters in stories like “Forks” or “Who Do You Love?” or “You Are What You Like” or “A Month of Sundays” feel authentic to me. The situations in which they find themselves are unusual, sometimes improbable, but for the most part they respond to those situations in ways that I found believable. (The very ending of “You Are What You Like,” where a woman confronts her husband’s high school buddy, didn’t fully convince me, but everything leading up to that ending—the arguments between the two old friends, the husband reflexively defending his friend afterwards, the husband’s guilt about what happens the next time he and his friend hang out—was full of “emotional verity.”) Were there any turns of phrase that made me stop reading and marvel at how amazing that string of words had been, and what a fabulous mind it must have taken to come up with such worthy assertions of imagination? There were not. Instead, there were characters and settings which I accepted, in which I became absorbed—where my concentration was only broken by the occasional false note, not by an author’s self-consciously virtuoso performance.

I certainly haven’t read all of Inside, but I’m intrigued by the opening scenes, in which a therapist named Grace stumbles onto a man attempting suicide while she’s cross-country skiing, then ends up taking him home from the hospital. Yes, it tests my suspension of disbelief that Grace would go along with Tug (the failed suicide) telling the attending physician that she’s his wife and they were having a fight, but it works well enough in context—and I’ve seen far, far more implausible “meet cutes” in a lifetime of reading—that I’m willing to let it slide to see where Ohlin takes these characters. It’s real enough that I want more; as in Signs and Wonders, my reaction isn’t “Alix Ohlin is such a genius,” it’s “I’m into this story.” Which may, in fact, be the most powerful indication of Ohlin’s particular genius.

It’s just too bad that it took one of the shittiest book reviews I’ve ever had the displeasure of reading to bring me back to an author I already knew I liked.

18 August 2012 | read this |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.