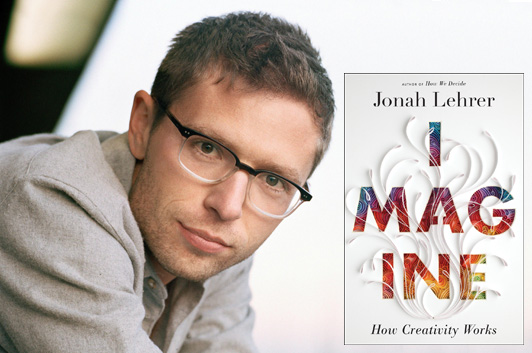

Read This: Imagine and Magic Hours

Nina Subin

I haven’t had a lot to say about the controversies surrounding Jonah Lehrer and Imagine—and you’ll notice that I’m not putting up my usual link to Powells.com so you can look at and buy the book. That’s because it’s been pulled from the market after a journalist discovered that Lehrer had fabricated quotes which he attributed to Bob Dylan in the opening chapter. Even if that revelation hadn’t come less than a month after a brouhaha over Lehrer “plagiarizing” himself in his blog posts for The New Yorker, this would still have been a book-killer; since the knives were already out for him, it soon became a question of whether he’d have any writing career left at all.

I didn’t have any particular problem with Lehrer recycling his own work; sure, he could’ve thrown in a “As I said in This Magazine” when appropriate, but not doing so wasn’t nearly as awful as, say, Fareed Zakaria’s recent lifting and tweaking of an entire paragraph from a Jill Lepore piece in The New Yorker, which is pretty much the exact form of plagiarism that drove Ruth Shalit—hands up; who remembers Ruth Shalit?—out of magazine journalism. My opinion was undoubtedly subjective: Not only was I a fan of Imagine, I’d also done an interview with Lehrer shortly after the book’s release. He came across as a genuinely nice guy, and I respected and admired the way he’d been able to leverage his interests into meeting and interviewing some of his creative heroes. So, yeah, totally willing to give him the benefit of the doubt the first time around.

Once it turned out that he’d made parts of Imagine up, that position became harder to maintain; at the same time, I didn’t particularly feel like dogpiling on him at his weakest moment. Part of it was that the blowback from his actions affected his publisher, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, which is also my former employer. So I knew the people who were forced to deal with recalling the book from stores and fielding questions from the media— under different circumstances, I could’ve been one of the people forced to deal with it—and I didn’t want to add to their troubles. And, honestly, I still liked the book that I read, and the author that I met.

Let me elaborate on that: I know now that there are fundamental problems with Imagine, and that there may turn out to be more problems of a similar nature. (UPDATE: In fact, they’ve already started to turn up.) And though it’s impossible to set those problems aside completely, when I look back at the book I read, at the time I read it, I recall a book that had a lot of interesting things to say about creativity and what we can do as individuals and as a culture to cultivate and encourage that creativity. Even before the big problems came up, people were arguing about the conclusions Lehrer had reached, and the validity of his reasoning—but Imagine was a book that engaged people, and instigated important discussions, and Lehrer was clearly, deeply engaged with the subject.

In a sense, I think that when Lehrer combined statements that Dylan made years apart into one statement, or when he made stuff up outright, he wasn’t just cheating readers—he was cheating himself, because the theories he’s putting forward deserve the best possible argument. Now, instead of being considered right or wrong on their own merits, the ideas in Imagine will always be undermined by nagging questions about whether we can take what’s on the page at face value. And that’s a damn shame. If you can find a copy of Imagine somehow, I would encourage you to read it with an open mind—think about what he’s saying about creativity and collaboration, and ask yourself it it makes sense.

If you can’t find Imagine, though, I would encourage you even more strongly to track down a copy of Tom Bissell’s Magic Hours, a collection of about a decade’s worth of journalism and cultural criticism focusing on creative people at work. I’ve been dipping into the book at spare moments for the last month, and it’s just a real delight. There’s a keen observational power to his reporting, but also to his reading. I’d vaguely remembered a piece he’d written for The Believer about a decade ago considering a group of self-styled literary rebels. Rereading it, I was struck by his willingness to approach them with empathy, even when he was unrelenting in his analysis of their deluded assholery. That level of thoughtfulness is evident in every part of Magic Hours, whether he’s talking about his role in bringing Paula Fox back into print or describing the moment he was able to tell Werner Herzog how his films had inspired him.

(Again, I’m being somewhat subjective here: Bissell and I crossed paths frequently when I first moved to New York and began attending literary events. The best, least presumptuous way to describe it might be to say he’s the kind of professional acquaintance I’ve always been glad to run into—although it’s been a long time since that happened—and it’s always been nice to see that he’s doing well. Am I more inclined to read Bissell because I consider him one of the good guys? So be it.)

Anyway, it’s that type of thoughtfulness and openness that I think I can see in the best moments of Imagine, that I’m certain Jonah Lehrer possesses in his best moments, and that—despite the likelihood that he’ll always be “that guy who made up the Dylan quotes” in the media’s eyes—I hope he’ll one day have the opportunity to demonstrate to us again.

14 August 2012 | read this |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.