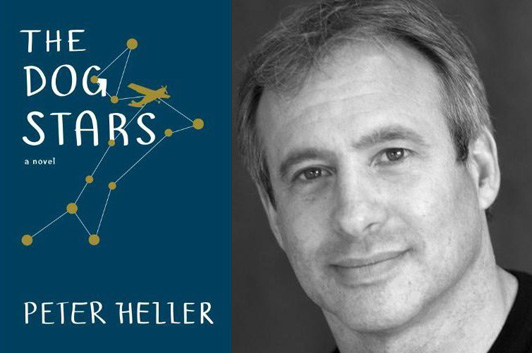

Read This: The Dog Stars

photo: Tory Read

Earlier this summer, I began writing the occasional book review for the Dallas Morning News; my first article was about David Dufty’s How to Build an Android, an account of a university computer science lab’s effort to build a robotic simulation of Philip K. Dick. (And it worked, too, at least until they lost its head…)

For my second Morning News piece, I keep up the science fiction vibe with a look at Peter Heller‘s debut novel, The Dog Stars. Here’s how I described the context of its publication:

In a little over a half century, life after the end of the world has subtly shifted from a topic fit mostly for science fiction, as in Richard Matheson’s I Am Legend (1954) or Walter M. Miller, Jr.’s A Canticle for Liebowitz (1960), to the stuff of top-shelf literary fiction, most notably Cormac McCarthy’s The Road (2006).

The Dog Stars positions itself squarely in the latter camp. Although there are scattered references to the superbug that set the novel’s disaster in motion, including a rumor that it might have been a biological weapon, Heller’s focus is firmly fixed on Hig and his shifting emotional state.

Hig is the novel’s 40-year-old narrator, a widow who lives in an abandoned Colorado airport with his aging dog and a sharpshooting survivalist named Bangley. Bangley drives Hig nuts, but he also keeps the two of them alive, and Hig can always get away for a couple days in his small plane. His frustration mounts, though, until one day he sets out after a possible hint of other survivors… As I put it, the book “can feel less like a 21st-century apocalypse and more like a 19th-century frontier narrative… [with] echoes of Grizzly Adams or Jeremiah Johnson,” including some intensely violent scenes. But it’s also a book of “quiet, poetic beauty,” driven not by the plot device of the end of the world but by Hig’s voice. I’d actually set this book aside when I first heard about it, because I didn’t feel up for another literary run at science fictional themes at that moment, but I’m glad that the Morning News encouraged me to take a second look—this is a great story, and I’m interested now in tracking down some of Heller’s nonfiction writing.

29 August 2012 | read this |

Lillian Ann Slugocki: The Mythic Arc of The Blue Hours

I met Lillian Ann Slugocki in 2001, shortly after she and Erin Cressida Wilson had published The Erotica Project, a series of monologues that they’d co-written for various theatrical and print formats. I’ve stayed in touch with Lillian over the years, so I was delighted recently to hear that she’d taken the plunge into digital publishing with The Blue Hours, a Newtown Press ebook for the Amazon Kindle that has its origins in a serial she wrote for Salon shortly after the success of the Project. In this essay, Lillian talks about the challenges of expanding the story well beyond its original size, and the dramatic solution she found to give the novella its final shape.

I met Lillian Ann Slugocki in 2001, shortly after she and Erin Cressida Wilson had published The Erotica Project, a series of monologues that they’d co-written for various theatrical and print formats. I’ve stayed in touch with Lillian over the years, so I was delighted recently to hear that she’d taken the plunge into digital publishing with The Blue Hours, a Newtown Press ebook for the Amazon Kindle that has its origins in a serial she wrote for Salon shortly after the success of the Project. In this essay, Lillian talks about the challenges of expanding the story well beyond its original size, and the dramatic solution she found to give the novella its final shape.

When Diary of a Divorce, a series of short erotic stories, debuted on Salon, it got quite a bit of attention from editors at major publishing houses. Which was great. I got to work expanding 10,000 words to 60,000. Except I really didn’t have a strategy.

This was my first foray into fiction writing; prior to this, I’d written plays. I was still flush from the success of The Erotica Project, co-authored with Erin Cressida Wilson. I kept the diary format, but really didn’t invent an arc for the story. It’s not surprising that when it was submitted to these editors, some of them said, “This reads like a memoir not a novel, make it more like a memoir.” And some said, “If this is a novel, it needs more narrative tension.” I tried to please all the editors, both camps, and I don’t think this ever ends well for any writer. When I walked away from it, I simply didn’t know if it was really memoir or fiction, or fictionalized memoir. So I put the “diary” away for a very long time.

Last fall, I was reading The Writer’s Journey by Christopher Vogler. It’s geared towards screenwriters, and the classic three act structure. But since he draws on Joseph Campbell’s The Hero with a Thousand Faces, I knew, obviously, this is one of the classic narrative structures, practically a template, maybe the only template for telling a story.

I had fallen in love with narrative structure while getting an MA at The Gallatin School. In particular I loved V. Propp’s Morphology of the Folktale Like Vogler and Campbell, he distills story telling down to its purest, simplest forms. I was doing all this research because I was writing another book, Scheherazade. I became convinced that despite the fact that the hero is almost a universally male narrative, I could still subvert it, twist it, use for my own purposes—a female narrative.

When I had that book all mapped out, I suddenly realized that this strategy would be perfect for Diary of a Divorce. I hadn’t thought of the piece in a long time, but it always haunted me. I knew there was a great story in there somewhere, and here was the mechanism for teasing it out.

27 August 2012 | guest authors |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.