Stanley Plumly, “Lapsed Meadows”

photo: Ron Hogan/GalleyCat

Wild has its skills. the apple grew so close

to the ground it seemed the tree was thicket,

crab, and root, and by fall would look like brush

among the burdock and the hawkweed, as if at heart

it had been cut and piled for burning.

Along the edges, at the corners, like failed fence,

the hawthorns, by comparison, seemed planted.

Everywhere else there was broom grass, timothy,

and wood fern, and sometimes a sapling,

sometimes a run of hazel; sometimes, depending,

fruit still green or grounded and rotting underfoot.

I remember, in Ohio, fields of wastes of nature,

lost pasture, fallow clearings, buckwheat

and fireweed and broken sparrow nests,

especially in the summer, in the fading hilltop sun,

when you could lose yourself by simply lying down.

Who will find you, who will call you home now, at dusk,

with the dry tips of the goldenrod confused”

with a little wind, filling in for what’s left of the light?

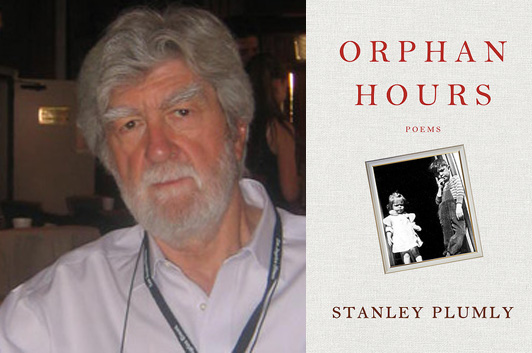

Orphan Hours is the eleventh book of poems by Stanley Plumly; I took this photo of him in 2008, after he’d just won the Los Angeles Times Book Prize for Old Heart. Other poems in this new collection include “Cancer (originally published in The New Yorker), “Afterward” (Kenyon Review), “Vesper Sparrow” (The New Republic), and “Verisimilitude” (The Atlantic). “Amidon Christmas Tree Farm Cardinal” was originally published in The Atlantic as “Cardinal.”

13 July 2012 | poetry |

Penelope Trunk’s Farewell to Publishing

photo: PenelopeTrunk.com

When Penelope Trunk decided to release her latest book, The New American Dream, through an independent, digital-only publishing company called Hyperink (“working directly with domain experts to publish beautiful, high-quality eBooks”), there was a lot of talk—but it wasn’t about the book or its contents. Instead, it was about a blog post Trunk wrote about her very bad breakup with Big Publishing, or rather with the big publisher that had originally given her an advance for this book. According to Trunk, it all fell apart when they started to talk about the marketing plans:

“Really, their call was just about giving me a list of what I was going to do to publicize the book. I asked them what they were going to do. They had no idea. Seriously. They did not have a written plan, or any list, and when I pushed one of the people on this first call to give me examples of what the publishers would do to promote my book, she said ‘newsgroups.’

“I assumed I was misunderstanding. I said, ‘You mean like newsgroups from the early 90s? Those newsgroups? USENET?'”

Conversations like this led Trunk to believe that she was better at online marketing than the people who were about to publish her book, and the presentation they put on to persuade her otherwise didn’t work. At some point during that meeting, she says, a “high-up guy” at the company told her, “If you don’t stop berating our publicity department we are not going to publish your book.†She called their bluff—and here I’m presuming that she had a really good contract with a clause stipulating that if she delivered a manuscript that they considered publishable, and then later decided not to publish, she could keep her advance. So she walked.

There’s been a lot of conversation around Trunk’s revelations. TechCrunch believes the blog post is “calls bullshit on traditional publishing,” while Digital Book World wonders who that publisher could have been, and I saw a lot of people discussing the plausibility of her version of events on Twitter. And, because the listing for The New American Dream in Amazon.com’s Kindle Store says it’s only 53 pages long, there’s some question as to how what she’s selling now compares to the book that was sold to the publishing house, because would they really have agreed to publish something that short?

11 July 2012 | theory |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.