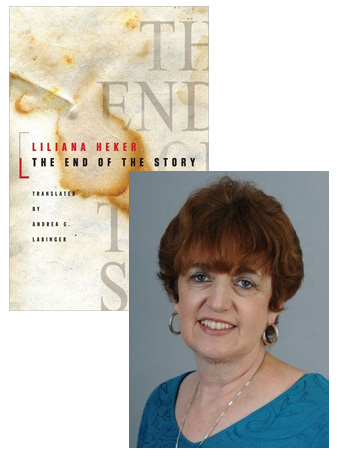

Andrea G. Labinger: The Story Continues

Liliana Heker’s The End of the Story is a powerful novel about Argentinean politics, a novel which sparked much controversy when it was published in 1996—particularly for its portrayal of a revolutionary who abandons her politics under torture and becomes an active collaborator with the ruling junta. Andrea G. Labinger, who’s translated many works by Latin American authors, wrote in a previous essay (see the link below) that she decided to take on The End of the Story “because I was attracted to its complexity as well as to the originality of Heker’s style;” it’s precisely because the novel’s political and literary tensions aren’t neatly resolved that it’s such a compelling story. In this essay, Prof. Labinger discusses some of the other questions she needed to address in formulating her approach to Heker’s prose.

There’s something vertiginous about writing an essay about translating a book about writing a book about the impossibility of telling a story. Too many “abouts,” for one thing. For another, as one perceptive reader of The End of the Story recently observed, the author grants few concessions to the reader. As is the case with most postmodern fiction, Liliana Heker makes us work for it: the complexity of her syntax only serves to intensify the multiplicity of narrative voices, dizzying time shifts, and moral ambiguity of the unsettling tale she has chosen to tell, like a tragic theme with variations, over and over again.

Despite these complications, a cursory synopsis is possible: Diana Glass, a severely nearsighted aspiring writer, determines to document the story of her friend and former classmate, Leonora, who became a Montonero rebel during the brutal military dictatorships that nearly destroyed Argentina during the 1970s and resulted in the death and “disappearance” of tens of thousands of people. For various reasons that the author painstakingly explains and which Diana herself attempts to elucidate in the course of framing her narrative, Leonora, after having been imprisoned and tortured, finally collaborates with her captors, providing them with information about the dissidents’ activities. Even more disturbing is the fact that Leonora eventually becomes her torturer’s lover, embracing her new role as informant with as much zeal as she had previously exhibited in the service of the Montonero rebels.

Diana, unable or unwilling to acknowledge her friend’s betrayal, continually revisits and reshapes her story, which somehow never solidifies for her: it blurs before her myopic, disbelieving eyes with each recounting. Ultimately the narrative thread is picked up by Hertha Bechofen, a Viennese World War II refugee and a writer herself. It is Hertha’s ironic, dispassionate voice that guides us to the conclusion.

Enter the translator. My first obstacle in choosing this book was ideological. For years I had desperately wanted to translate El fin de la historia, but Argentine friends—at least one of whom had been a political prisoner of the junta—tried to talk me out of it (see “To What End?: Translating Liliana Heker’s El fin de la historia and Related Narratives of the Argentine Proceso,” which appeared in 91st Meridian in 2007). Heker herself warned me that she is a “polemical” writer, and that the novel might be a hard sell. She certainly adopts an unpopular angle, to say the least, in depicting a former revolutionary as capable of being disloyal to her comrades, even when torture, the murder of Leonora’s husband, and threats of reprisals against her family contribute to the defection. What political stance would I appear to be adopting if I took on this book, I asked myself.

The second problem was stylistic. Heker liberally sprinkles her ultra-long sentences (some of these go on for paragraphs, or even pages) with parentheses (as I’ve just done), and dashes—sometimes disconcerting, always attention-grabbing—as well as the occasional italicized passage to denote those phrases that Diana jots down in her notebook, that is, the text-within-the-text. This labyrinthine style works well in Spanish but seem less natural in English, a language that tends to favor the terse and direct over the Baroque flow of the original. Such deliberately convoluted language presents a very common dilemma for the Spanish-to-English translator, who must decide whether to chop up the sentences into more digestible form at the expense of losing the author’s characteristic style or to preserve the complexity of the original and risk confusing the reader. Most of the time I chose the latter option, hoping that careful word choice and judicious punctuation would help clarify any potential obfuscation.

Occasionally, though, I found English to be a better vehicle than Spanish especially when pithy slogans or chants were involved. One of my favorites was the following verse, assonantal in the original but with a clipped, consonantal rhyme in translation:

Ay, ay, ay

qué lindo va a ser

el Hospital de Niños

en el Sheraton Hotel.Ay, ay, ay

Wouldn’t it be swell

to build a Children’s Hospital

in the Sheraton HotelTranslating The End of the Story was often a bumpy ride, but it was possibly the most rewarding translation project I’ve ever undertaken. I’m grateful to Liliana Heker for writing this remarkable tale, and to Stephen Henighan and Dan Wells of Bibiloasis Press for helping to bring it to fruition.

18 June 2012 | in translation |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.