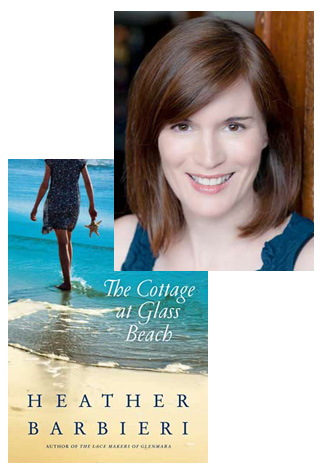

Heather Barbieri & The Novel as Remembrance

All novels are personal, of course, but The Cottage at Glass Beach holds a particularly special meaning for Heather Barbieri. Although the storyline, about a woman trying to resolve a mystery from her family’s past while she’s still reeling from a blow to her marriage, has little to do with Barbieri’s own experience, the novel’s themes of motherhood resonated deeply with her during the writing process, as she explains in this guest essay…

I’d just submitted an outline and sample chapters for The Cottage at Glass Beach to my agent when the news came. My previously healthy, active mother, the woman who was frequently asked what products she used to keep her appearance so young (answer: the old school version of Oil of Olay), had been flown to the emergency room here in Seattle. It took a day or two before the doctors realized she had one of the worst conditions possible, cerebral amyloidosis, from which there was no recovery. (C. a. is a little known member of the Alzheimer’s family of illnesses; there’s no treatment, no cure.) She never regained consciousness and died within a few days—better for her, given the prognosis; hard for us, as it is for so many who find themselves suddenly bereft.

Two weeks later, I had a book deal, but was struggling to get my bearings. As had been happening frequently since my mother’s death, a blue jay perched in the rhododendron bush across from my office window, trilling in what might have been interpreted as encouragement and staring me in the eye. It’s going to be all right, it seemed to say. Whenever I was feeling uncertain it, or one of its brethren, would appear to cheer me up at just the right time. (One of the birds had alighted on the dining room windowsill when we were telling my dad that Mom had passed away, tapping on the glass to get our attention.) Blue had been her favorite color, and the birds became her emissaries, signs and wonders, in a time of need.

A month or two went by. I put one word after another, one foot in front of the other, not sure if anything was making sense. I’d visit my dad in the house I grew up in whenever I could. My dad wanted to stay there, in the home they’d made together, the place that held our childhoods, so many art projects still proudly displayed, the place that held the memory of us. As I went through the rooms, there were indications that Mom was trying to keep track of things in the months before she died—that she might have known something was the matter with her. She was a writer too—of wonderfully detailed letters, of lists. Everything in the medicine cabinet was carefully labeled in her neat hand. Things to remember were posted on the fridge. It was all very thorough—too thorough—indications, perhaps, that something was wrong, but none of us noticed. Maybe she didn’t want us to. After all, nothing could have been done.

Each of us mourns differently. For me, what initially seemed like a daunting challenge of writing a novel in a few short months, became an outlet to process and express a profound loss and in doing so, discovering the transformation, the sadness and gifts that can come from such tragedies. The subconscious, so essential to the creative process, is no stranger to grief.

And so I wrote, five days a week, writing the story I’d told her about that December—she’d always been my sounding board, sharing ideas and reading recommendations. The story she knew, but changed too, focusing on a woman’s journey to find her way in the wake of a devastating betrayal, to protect her young daughters, and to solve the disappearance of her mother when she was a child. The book, this book, I would dedicate to my mother’s memory, lost and found.

17 June 2012 | guest authors |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.