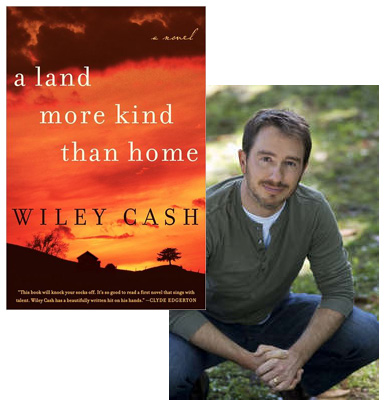

Wiley Cash on Hearing Voices

A few months back, I had the pleasure of meeting Wiley Cash at a luncheon his publisher, William Morrow, hosted to alert some folks to his debut novel, A Land More Kind Than Home. As he was telling us about the book, he mentioned something about the multiple first-person perspectives he used to tell the story—like an early chapter written in the voice of the local sheriff— and how he’d actually explored a few other possibilities from among the other characters, which he’d had to abandon for various reasons. And I thought to myself, “That’s a really cool insight. I bet a lot of people would be interested in hearing about this.” And, luckily for me, he thought it was a great idea as well.

“I didn’t know Pastor Chambliss had killed my big brother until later that night.”

This is the first line I ever wrote for what would become my first novel. It’s also the first voice I heard when I sat down to write the story; it belongs to Jess Hall, the nine-year-old younger brother of an autistic boy who’s smothered during a healing service in a little church in the mountains of North Carolina. The original plan was to write a short story from the perspective of Jess, a young boy who witnesses something he never should’ve seen, something he can’t quite understand. But then a strange thing happened; other characters wanted to speak—they wanted to tell their stories, they wanted the opportunity to defend themselves or to blame others or to apologize for the mess they’d made of things.

In this chorus of voices, I heard Adelaide Lyle, the eighty-year-old church matriarch and the community’s moral conscience. She wanted to tell me that she’d taken the children out of the church a decade earlier when the worship services turned deadly after a woman died from a snake bite. Adelaide wanted me to know that she felt responsible for the spiritual and physical wellbeing of the children under her watch, and that she never imagined such a tragedy could befall one of them. She wanted me to know that she’d stood up to Carson Chambliss once before, and she wanted me to understand that she wouldn’t be afraid to do so again.

I heard the voice of Clem Barfield, a local sheriff with his own painful past who’s called upon to solve the mystery of the young boy’s death. He wanted to tell me that he wasn’t from Madison County, that he’d always been an outsider, that he’d always been suspicious of the little church down by the river with the papered-over windows. He wanted me to know that his own life had been touched by tragedy years earlier when he lost his adult son, and he wanted me to understand that it takes a lifetime to build equity in loss, that only parents—not a church or a community—can fathom the pain of losing a child.

I heard the voices of other characters too. The first was Ben Hall, the boys’ father, a man whose pragmatic approach to the world left no room for miracles or the hand of the divine, a man who’d grown suspicious of his wife’s passion for the church and its mysterious leader. I felt Ben—I felt his confusion and his anger and his loss—and I could see him, red-faced and furious with his eyes full of tears as he tried to explain himself through his rage, but I couldn’t quite hear him as well as I heard the other characters. Perhaps this is because he lacked Jess’s emotional distance and confusion, Adelaide’s world-weary perspective, or Clem’s rational melancholy. Or perhaps I just couldn’t understand Ben, a man roughly my own age, because I don’t have children of my own, and like Clem says, I can’t imagine what it is to lose one.

26 April 2012 | guest authors |

Life Stories #6: Kambri Crews

In the sixth installment of Life Stories, my series of podcast interviews with memoir writers, I spoke with Kambri Crews about Burn Down the Ground, her account of growing up as the hearing child of deaf parents in a rural Texas community. One of the first things we talked about is what motivated her to tell this story:

“I work in the comedy business, and a lot of comedians—when they would find out about my story—they would kind of salivate, almost, over these awesome stories that I had, growing up in the wild, in the woods with these deaf people. Because they’re always mining their lives for material, their day-to-day lives or the past, to try to find something funny to say on stage. And here I’m sitting on this treasure trove of material, and not doing anything with it. Everyone just kept saying, ‘You’ve got to write a book, you’ve got to write a book!'”

It’s not all laughs, though: As her parents’ marriage falls apart, the teenage Crews is forced to observe as her father’s behavior turns increasingly violent—including a brutal assault on her mother that is dismissed as a routine matter by local law enforcement. Decades later, long after Crews had put her hometown behind her, she found out that her father was now being accused of attempted murder, and she needed to decide whether to steer the police towards the files on that earlier incident. (It’s not a spoiler when I tell you that the memoir is framed by a contemporary account of visiting her father in prison.) Because the interview took place shortly after the revelations that Mike Daisey had fabricated several of the details in his dramatic monologue “The Agony and the Ecstacy of Steve Jobs,” we also talked quite a bit about the obligations of truth telling in memoir. It’s a great conversation, and I hope you enjoy listening to it.

Listen to Life Stories #6: Kambri Crews (MP3 file); or download the file by right-clicking (Mac users, option-click).

22 April 2012 | life stories |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.