Read This: Recently Character Approved Writing

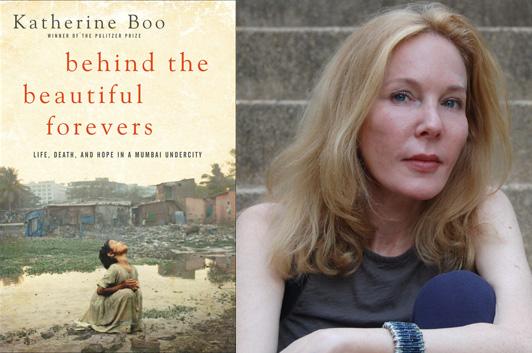

I have a freelance gig with the USA Network’s Character Approved blog, where I provide them with a weekly update on some of the best new books. I haven’t mentioned any of those books here in a few weeks, so I thought I’d round up some of my recent selections. For example, there’s Katherine Boo’s Behind the Beautiful Forevers. Boo spent years checking in on the micro-community of a Mumbai slum, and one family in particular. It’s an amazing piece of immersive journalism, and a drama that’s all the more powerful for being true.

When you know how much effort Boo put into getting the facts of her story right, it makes the debate that takes place in the pages of John D’Agata and Jim Fingal’s The Lifespan of a Fact that much more significant. Basically, D’Agata wrote an essay inspired by the suicide of a Las Vegas teenager, but decided that because he wasn’t writing “nonfiction,” but rather some kind of art inspired by facts, he wasn’t limited to those facts. Fingal, the fact checker assigned to that essay by editors at The Believer, felt differently, and pushed back on every one of D’Agata’s deviations from what could be verified.

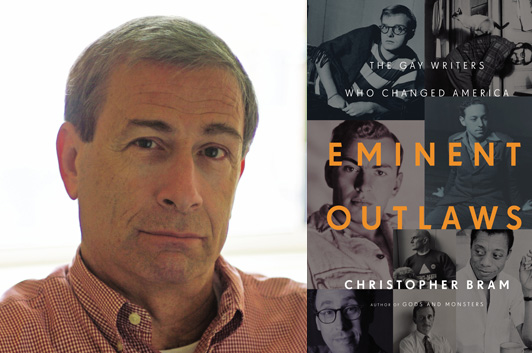

Christopher Bram’s Eminent Outlaws is a lively (if idiosyncratic) history of gay American literature from just after the Second World War to the present day. It’s got plenty of dish on authors like Gore Vidal and Truman Capote, or—as it moves closer to the present—Edmund White and Larry Kramer, and it subtly connects the impact these writers had on Bram’s own personal development to the broader cultural developments that have made it possible for gay authors to be more open about their identities—and for those identities to no longer be as radically shocking as they were for previous generations. Bram admits to one of the book’s most significant flaws, which is that it has nothing to say about the parallel progress of lesbian American literature, by pointing out that he doesn’t have much to say on that subject; it’d be a worthy thread for someone to pick up (as would the histories of other queer literatures, for that matter).

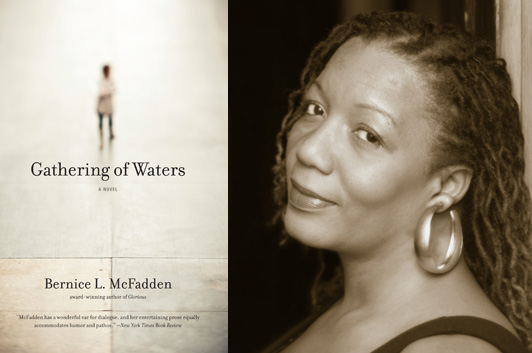

Then there’s Bernice McFadden’s Gathering of Waters, a highly imaginative retelling of the murder of Emmett Till in Money, Mississippi, in 1955. It’s not just that McFadden gives Till a young, black girlfriend who remains emotionally traumatized by his death even after she marries and leaves Mississippi. It’s that she gives that young girl a backstory that involves vengeful ghosts, a seduced preacher, and the Great Flood of 1927—not to mention the invoking of Hurricane Katrina. This novel’s definitely not going to be to everyone’s tastes, but I found myself intrigued by McFadden’s creative effort to bring some sort of healing karmic balance to the impact Till’s death had on the consciousness of Mississippi, the South, and the nation as a whole.

Looking at these selections in light of last month’s reflections on the gender imbalances in my book reviewing, the obvious first reaction is to pat myself on the back for hitting the 50-50 mark, and for hitting upon all sorts of other diversities besides. That would be both premature and prideful—and though I have some idea of how I’m planning to continue to live up to my chosen goals in writing about books in the months ahead, we’ll see how they play out.

28 February 2012 | read this |

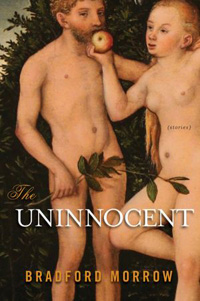

Author2Author: Bradford Morrow & Peter Straub

I had my eye on Bradford Morrow‘s short story collection, The Uninnocent, and Peter Straub‘s short novel, Mrs. God, from the moments (a few days apart) that they arrived in my inbox. I’ve been a fan of both writers for decades, admiring the ways that they’ve applied their literary sensibilities to the themes of horror literature. (Below, Brad invokes the term “gothic,” which in some ways has become to the horror/dark fantasy genre what “slipstream” was to science fiction—a way for literary critics to identify the sophisticated stuff.) What I didn’t realize, but probably should have, is that the two writers knew each other well, and were more than happy to send each other a few questions about these books, and about the fuzzy territory where genre and literary fiction overlap.

Bradford Morrow: As a horror writer who has achieved international commercial success but also stayed true to your serious literary roots, you have often been fearlessly innovative in the way you’ve crafted your narratives. Would you mind talking a little about how you perceive the divide between so-called “genre” fiction and “literary” fiction? My sense is that there is a growing number of serious writers who ignore this critical distinction altogether.

Bradford Morrow: As a horror writer who has achieved international commercial success but also stayed true to your serious literary roots, you have often been fearlessly innovative in the way you’ve crafted your narratives. Would you mind talking a little about how you perceive the divide between so-called “genre” fiction and “literary” fiction? My sense is that there is a growing number of serious writers who ignore this critical distinction altogether.

PETER STRAUB. I’ve been seeing for years that the distinction between genre fiction and literary fiction has been erased by a number of writers whose work assumes that the genre markers can be overlain atop the literary, thereby making the question of a real distinction purely academic. John Crowley and Kelly Link, both of whom began with an at least theoretical attachment to science fiction and fantasy, are the poster children for this tendency. Dan Chaon and Brian Evenson are literary writers whose work falls naturally into considerations of horror and the gothic. For decades. Stephen King has been more or less devouring attributes of the literary stance and using them to expand the possibilities to be found within horror.

Of course many genre writers happily go on using the toolkit/toybox handed to them by previous generations, writing pseudo-Lovecraft stories, pseudo-Sherlock Holmes stories, updated hardboiled novels, etc. This impulse comes from a very common desire to replicate deep satisfactions by echoing the forms and gestures of their sources. Hence the many variations on the Tolkien model for fantasy.These replications, most of which are worthy, are grounded in the desire to create pleasure, suspense, and gratification in the reader. None of them, however, go any farther, so the experience of a prolonged reading of such writers is like that of meeting child after child, brothers, daughters, first cousins, grown-up sons and teenage sons, of the same family. But even the most literary of genre-based writers wishes for a positive pleasurable response from the reader (though it may be for a more complex variety of pleasure than that offered by a Rex Stout novel, Rex Stout being for these purposes an adult son of Sherlock Holmes). There will never be any genre-rooted variation on Finnegans Wake, for example, though I think The Good Soldier is practically begging to be used in this way.

And now, a Question for you, my dear friend: You have demonstrated, it delights me to observe, an unusual openness, for a literary writer of the purest kind, to the possibilities to be found in genre writing, which is most often either dismissed out of hand or patronized by authors of literary fiction. And most if not all of your more recent work has ties to mystery or horror, especially The Diviner’s Tale and The Uninnocent. To me, The Uninnocent is really filled with horror stories, with joyous embraces of any number of horror’s stances, attitudes, gestures, and favored narrativities (a word I think I just made up.) So I want to ask you how you got that way, and what this general artistic evolution of yours means to you. One would think that such a movement would necessarily be toward a general narrowing of focus and intent, but in you it seems to involve a kind of widening-out, a kind of opening to a different Otherness. How could this have happened to a devoted student of Gass, Barth, and Gaddis?

Bradford Morrow: My interest in the gothic—and by extension, horror—dates back at least as far as my second novel, The Almanac Branch, in which the narrator, Grace Brush, may or may not be hallucinating electric-pink light people in the ailanthus tree outside her bedroom window. I co-edited with Patrick McGrath an anthology, The New Gothic, in 1991, which brought together writers as wildly diverse as Anne Rice and Angela Carter, Ruth Rendell and Kathy Acker, Emma Tennant and William T. Vollmann. In other words, the genre writers alongside literary writers, so-labeled. A few of the stories in The Uninocent also date back to the same period in the ’90s, including “The Road to Nadeja” and the title story itself.

Bradford Morrow: My interest in the gothic—and by extension, horror—dates back at least as far as my second novel, The Almanac Branch, in which the narrator, Grace Brush, may or may not be hallucinating electric-pink light people in the ailanthus tree outside her bedroom window. I co-edited with Patrick McGrath an anthology, The New Gothic, in 1991, which brought together writers as wildly diverse as Anne Rice and Angela Carter, Ruth Rendell and Kathy Acker, Emma Tennant and William T. Vollmann. In other words, the genre writers alongside literary writers, so-labeled. A few of the stories in The Uninocent also date back to the same period in the ’90s, including “The Road to Nadeja” and the title story itself.

That said, this is a challenging question, Peter, because in the past my novels fluctuated from mystery/gothic-centered narratives to fairly large scale political/historical “literary” investigations. The more I think about life, I think about it as a very dark place. These latest books also embrace a necessary chiaroscuro of hope and faith. My view of the gothic is that, well, the focus is on evil, entropy, illness mental and otherwise, all things dark. It concurrently and inevitably juxtaposes with good, light, sanity, and so forth. One of the reasons I have become so increasingly interested in the gothic (and even horror) is because it offers me a rich opportunity to explore that ineffable thing that resides in the heart of the most diabolical sociopath, and that is a fundamental, albeit often paltry, goodness.

20 February 2012 | author2author |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.