The Story That Inspires Diane Williams

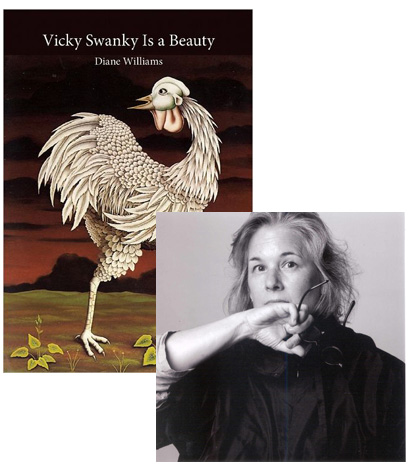

The short-short stories in Diane Williams’ Vicky Swanky Is a Beauty have a dream-like quality to them. Which is a statement that gets overused a lot in fiction, but it really does apply here; the stories take place in a world where objects and people depicted in sharp detail in a world that runs on its own surreal logic, where the rules of engagement can change from sentence to sentence. Another way to think of Williams’ stories is like poetry: Though they gesture towards narrative, they seem more actively concerned with living inside a moment, giving it a unique form of expression that reflects the perception rather than the “objective” “reality.”

Williams’ contribution to the “Selling Shorts” series is markedly different from just about any of the others. As with her fiction, though, after sitting with it for a while I’ve come to a new understanding of the world—although, perhaps, in this case it’s more accurate to say an understanding that had long been embedded in my subconscious was brought forcefully up to the surface, making the doubts she expresses about her offering quite unfounded.

The most influential—the most inspirational story I can think of?—that’s the poor, thin tale I repeat incessantly to serve my grand purpose:

YOU CAN TELL A STORY

You want to tell a story?

You can tell a story.

Try now!Am I fair to Ron Hogan here?— who offered me the opportunity to share something of value—and who likely expected something more from me and better?

I have told the truth, but perhaps this is not fair or helpful. Therefore, I’ll direct you to a livelier story cited by Chaim Potok in his foreword for Martin Buber’s Tales of the Hasidim. This story is potent enough to produce a miracle cure for the lame man who tells it and this story concludes with the exhortation, “Now that’s the way to tell a story!â€

(After that tantalizing hint, I’m sure I’m not the only one who’s headed to the library to track down a copy of that story at the first opportunity…)

17 January 2012 | selling shorts |

Nancy Pearl’s Amazon Expedition

When I wrote my notes towards an ambassador of literature, and mentioned Seattle librarian Nancy Pearl, I’d forgotten that she’d been the inspiration for Archie McPhee’s Librarian Action Figure back in the day. I also didn’t realize that Pearl would be back in the news so soon: On January 11, Amazon.com sent out a press release, announcing that she’ll be curating a “Book Lust Rediscoveries” series, named after her previous collections of reading recommendations. The way it works is this: Nancy Pearl will select approximately six out-of-print titles each year; Amazon.com will acquire the rights to those books and then republish them for the Kindle (and as print-on-demand trade paperbacks).

When I wrote my notes towards an ambassador of literature, and mentioned Seattle librarian Nancy Pearl, I’d forgotten that she’d been the inspiration for Archie McPhee’s Librarian Action Figure back in the day. I also didn’t realize that Pearl would be back in the news so soon: On January 11, Amazon.com sent out a press release, announcing that she’ll be curating a “Book Lust Rediscoveries” series, named after her previous collections of reading recommendations. The way it works is this: Nancy Pearl will select approximately six out-of-print titles each year; Amazon.com will acquire the rights to those books and then republish them for the Kindle (and as print-on-demand trade paperbacks).

The series begins with Merle Miller’s A Gay and Melancholy Sound, which looks like one of those sprawling novels about coping with alienation in post-war America—you know, the kind where you wouldn’t be surprised if Douglas Sirk or Vincente Minelli had turned it into a Technicolor blowout—and was first published in 1961. (But, hey, for $5.99 on the Kindle, I may well wind up giving it a try.) Then there Rhian Ellis’s After Life, a psychological thriller published in 2000. So, from the onset, it seems like Pearl is doing exactly the sort of thing I praised her for in that previous post: She digs just that much deeper to come up with the cool book you haven’t heard about, and now, with Amazon’s backing, she’s in a better position than ever to both call people’s attention to that book and make it easier for them to read it.

Because Pearl is working with Amazon, it’s not unexpected that a backlash would occur even before the deal was official; as Seattle’s indie newspaper The Stranger put it, “many of the local librarians and independent booksellers who supported her… will feel disappointed, and even betrayed.” There are legitimate concerns about Amazon’s behavior as a bookseller, both with regard to how it deals with competition and how it is attempting to wield influence over book publishers—in particular, with respect to this issue, I’d say there’s a reasonable argument to be made against one mega-corporation accruing too much cultural influence. (As in, today it looks like Amazon’s creating a more diverse literary market, but what happens if they eliminate enough competition that some of that diversity dries up?)

It’s too easy to brand Pearl a “sell-out,” though, not to mention that it’s a sanctimonious putdown. Is everybody who’s gone to work for, or cut deals with, Amazon’s publishing division in the last year a sellout? Well, how big does a publishing company have to be before working there, or signing a book deal with them, makes you a sellout? I’ve thought a lot about this over the years, “that old punk rock question of authenticity versus assimilation” as I said in an interview during the early book blog boom. I’ve come to believe that fetishizing “authenticity” is self-destructive; cutting yourself off from the potential to wield cultural influence in the matters about which you’re most passionate just because somebody, somewhere might decide you’ve been “co-opted” is a sucker’s move.

(That’s not to say we should all go work for the mega-corporations. When I talk about fetishizing authenticity, I’m not saying every effort to live with integrity is self-absorbed or arrogant. Sometimes the terms you’re being offered are truly unacceptable, ask you to make too many compromises, and should be rejected. Sincere, reflective consideration of your values is not the same thing as a knee-jerk rejection in the name of “keeping it real.”)

All of which is a roundabout way of saying that, when I see Book Lust Rediscoveries, I see a woman who has dedicated her professional career to encouraging people not just to read the books she thinks are wonderful, but to read broadly enough to discover their own wonderful books, and who’s been presented with the resources to take that mission to a higher level—not just to reach a new audience (albeit one that no doubt overlaps substantially with her existing NPR fan base) but to obtain for that audience some books that were previously unavailable to them. Whether or not the specifics of Nancy Pearl’s deal with Amazon would make you or me comfortable, she obviously believes it’s the right deal for her. So let’s see what happens, and what other books will come back into print as a result.

13 January 2012 | theory |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.