Read This: In Other Worlds & 11/22/63

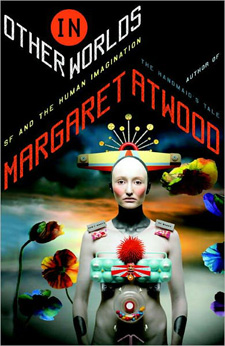

Yesterday, I had a review in Shelf Awareness for Readers, talking about In Other Worlds: SF and the Human Imagination, a collection of essays where Margaret Atwood elaborates on her relationship to science fiction—what she thinks it is, and why she wasn’t writing it all those times you thought she was writing it, although she has tried writing it and she likes some of the things other people have done with the genre.

Yesterday, I had a review in Shelf Awareness for Readers, talking about In Other Worlds: SF and the Human Imagination, a collection of essays where Margaret Atwood elaborates on her relationship to science fiction—what she thinks it is, and why she wasn’t writing it all those times you thought she was writing it, although she has tried writing it and she likes some of the things other people have done with the genre.

I found a lot of things to like in In Other Worlds, but I wasn’t completely satisfied, and in a paragraph that was excised from the final, shorter version of the review, I explained why:

“The problem is that this is all rather a hodgepodge: While the opening section does offer a cohesive theory on the literary roots of modern science fiction—including some interesting glimpses at Atwood’s early academic specialization in a tradition she identifies as the “English metaphysical romance”—the middle section basically extracts SF-themed material from the more expansive essay collection Writing With Intent and adds a few reviews that she wrote after that book was published. Readers will learn that science fiction contains ‘all those stories that don’t fit comfortably into the family room of the socially realistic novel or the more formal parlour of historical fiction,” but they’ll only gain scattered impressions of what those stories might be like, not a comprehensive critical history such as you might

find in the late Thomas M. Disch’s (highly opinionated) The Dreams Our Stuff Is Made Of.”

It’s basically a question of how tightly Atwood ties all her disparate thoughts on science fiction together: None of her thoughts are uninteresting—in fact, they all struck me as sound, although the opening essays are a bit conventional—they just didn’t seem to gel for me. But she’ll give you plenty to think about, so I encourage you to check the book out if you get a chance, anyway.

I had another review in the daily Shelf, taking on Stephen King’s 11/22/63, a nearly 900-page fantasy about a high school English teacher who’s shown a hole in the space-time continuum that leads back to 1958 and is recruited to spend five years in the past, verify that Lee Harvey Oswald wasn’t part of a conspiracy, and then stop him from assassinating John F. Kennedy. As a story, though, that’s practically an abstraction, even to the protagonist, so King gives Jake Epping more substantial personal motivations to go back in time and then stay there—first to right a tragedy that befell one of his adult GED students as a child, then to preserve his relationship with a librarian in a small town outside Dallas. As I wrote, 11/22/63 “reveals the capacity of ordinary people for extraordinary moments of love and courage,” but keep in mind: When Stephen King puts his characters to the test, he tests them hard.

(And, yes, King fans: Not only does the second act take place in Maine in 1958, it takes place in exactly the town you’d want it to, under those circumstances.)

26 October 2011 | read this |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.