Lewis Shiner and the Music of Tango

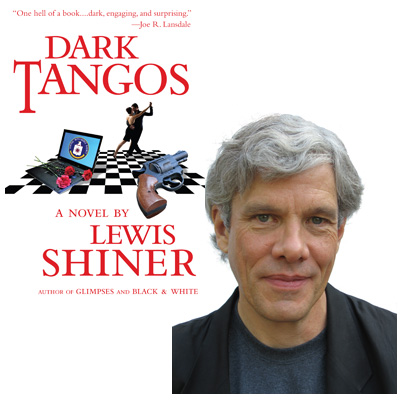

It’s a pleasure to be hosting Lewis Shiner as a guest author on Beatrice today—Lew has been one of my favorite authors for decades, and was present at one of my most magical bookstore experiences ever when Brian Wilson came by Dutton’s Brentwood Books to check out a reading from his 1993 novel Glimpses. His latest novel, Dark Tangos, contains a passion for tango as intense as the love of rock music evident in Glimpses or Say Goodbye, but it’s also a compelling political thriller with powerful emotional relationships at its core. To call attention to the book, Lew’s appearing at several blogs this week; he’s already posted about the intersection of the novel’s storyline and his philosophy of nonviolence for John Scalzi’s Whatever, and about how they dance in Argentina for Gwenda Bond’s Shaken & Stirred. Today he’s sharing some of his favorite musical selections with us, and after you’ve read these three essays, you’ll probably want to check out where he’s headed next. And to track down a copy of the novel, too!

In a reversal of the usual dance craze chronology, tango music didn’t exist when the dance was first invented.

It’s fairly common knowledge that tango, the dance, evolved in the brothels of Buenos Aires somewhere around the middle of the nineteenth century. It was a way for the clientele to pass the time as they waited for the working girls, who were generally in short supply. Most of the customers were European immigrants, and they probably danced to popular music from the Continent, including the habanera, one of tango’s most recognizable ancestors.

The music we now associate with tango, with its signature combination of bandoneon, violin, and piano, really began to take off in the early years of the twentieth century. As the music became more popular and was played in larger and larger venues, the orchestras got bigger and bigger to fill the rooms—this was before amplifiers were commonly available. During the Golden Age of Tango, from 1935 through 1950 or so, it was not uncommon for tango orchestras to have four bandoneon players, two or three violins, a viola, stand-up bass, piano, and one or more vocalists. These large orchestras, like the big swing bands in the same era in the US, were capable of stunning power, rich emotionality, and subtle counterpoint. The music of this era forms the heart of the tango canon.

I’ll spend the rest of this piece talking about some specific orchestras and recordings from that canon, including some of the ones I mention prominently in my new novel, Dark Tangos, which is set in the tango subculture of Buenos Aires. Tastes in tango music vary wildly, but these orchestras are to tango what Benny Goodman and Count Basie are to swing music—the household names that you’ll hear at nearly every milonga (tango dance party) the world over.

I’ll also recommend recordings for each orchestra, but don’t expect to find most of them at the big online music retailers. You’ll probably have to order them from Argentine web sites, where the favorable exchange rate makes this less painful than you might think. Zivals has a great selection and is very reputable. There are two main series that are easy to find and reliably authentic: Tango Argentino from BMG, and Reliquias from EMI. Authenticity can be an issue, as many orchestras rerecorded their hits periodically, often in inferior versions.

Juan D’Arienzo is probably the most beloved of the “guardia vieja,” the old guard, who were eclipsed by the more romantic orchestras of the 1940s. D’Arienzo’s most famous tangos are comparatively spare and staccato, but have an irresistible rhythm for dancing. I recommend Sus primeros éxitos vol. 1 (“His First Hits”) in the Tango Argentino series.

Carlos Di Sarli provides the soundtrack to countless beginning tango classes, yet dancers never get tired of his lush, dynamic sound. “A la gran muñeca,” “Rodriguez Peña,” and “El amanecer” are among the songs you’ll hear over and over at milongas, and you’ll find the classic versions of them on Tango Argentina’s Instrumental.

Tango vocals can be an acquired taste, and one not always easily come by. They can sound bombastic and annoyingly mannered at first, and sometimes later as well. For my money, Miguel Caló had some of the best singers in the business, and gave them great melodies to work with. Miguel Caló, #16 in Lantower Records’ excellent Grandes del Tango series, is a two disc set that includes such heartbreakers as “Que falta que me hacés.”

Osvaldo Pugliese is nearly as famous for his leftist politics as he is for his complex, dynamic, and powerful tangos. He is looked upon as a secular saint in Buenos Aires, along with such icons as Evita, Che, and Borges. All three volumes of his Instumentales inolvidables (Unforgettable Instrumentals) on Reliquias are wonderful (his singers really do take some getting used to), and I particularly recommend volume 3 for his all-time classic “Gallo ciego.”

My personal favorite Golden Age orchestra is that of Alfredo de Angeles, whose cascading string arrangements are unmatched for ethereal beauty. His rendition of “La cumparsita”—the traditional last tango played to signal the end of a milonga, and recorded by virtually every tango orchestra in history—is the best I’ve ever heard. “Pavadita” is my favorite tango to dance to, full of tension, swirling melody, and dramatic pauses. You can hear both on the Tango CD bearing his name in EMI’s From Argentina to the World series.

Starting in the late 1990s, tango had a renaissance in Buenos Aires. Young musicians with radical haircuts and reverence for tango tradition (Fernandez Fierro, Orchesta Tipica Imperial, and many more) put big orchestras on the street and into venues better known for rock shows. Meanwhile, the tango electronico movement (Gotan Project, Carlos Libedinsky’s excellent Narcotango) created a hybrid that’s now a staple at most milongas.

But there’s something about those classic tangos, with the crackle of the original 78 recording indelibly woven into the sound, that evokes the giant ballrooms of the Golden Age—impossibly elegant and romantic, gone forever.

7 September 2011 | guest authors |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.