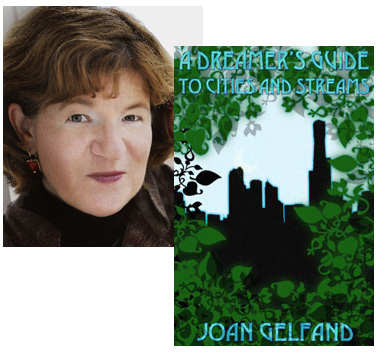

Joan Gelfand, “Poets House Walk”

Across Brooklyn in a city dense

With watery dreams, a procession

Of crazy lovers strike out

To hear poetry recited mid-span.

Hum of traffic roars approval.Toward DUMBO through the mist

Poets, strivers, drivers, divers

Graying profs, groupies, gurus hoof it,

To see hundred-year-old Kunitz carouse.We stalk poetry across the bridge

In a town distracted, manufacturing

Your next thrill, and your next.Bicycle tires tharump over

Old pocked, trampled wood.

Rush of water slaps girders

Shivers of bridge as wet drops

Shatter against metal deck.The jig was up. It rained.

All readings canceled.Finally, torrents gave way

To June light, shadow slant

Wide angles of cable, long stripes

Falling across beaten planks.

In the absence of poems,

Gorgeous geometry,

Engineering, poetry, and the wonder

Of holding things aloft.

Joan Gelfand will be reading at the Jefferson Market Library tonight at 5:30 p.m. with local poets Jane Ormerod, Toni Quest, and Karen Hildebrand in an event sponsored by the Women’s National Book Association (of which Gelfand is the former president). Other poems from A Dreamer’s Guide to Cities and Streams include “Venezia,†“Summer,†“Cupid,†and “Torqued Torus†(all in Poetry, the last in substantially different form as “Torqued—for Richard Serraâ€). There’s also three poems at StrangerRoad.com.

6 June 2011 | poetry |

Read This: The Borrower

Last week, while I was interviewing authors at BookExpo America, my latest Shelf Awareness review ran—and it’s a change of pace from my usual science fiction/fantasy fare. Rebecca Makkai’s debut novel, The Borrower, is the sort of story which, had it been published ten years ago, or even five, might have been unironically published as “chick lit.” Or maybe not: Makkai has a three-year consecutive streak of appearing in the Best American Short Stories anthologies, so she could easily be positioned in the same literary matrix in which authors like Curtis Sittenfeld have flourished. As it is, there’s both literary and commercial potential here, which is why I wound up describing The Borrower as “a young woman’s ‘dramedy’ in the vein of early Jennifer Weiner or Marian Keyes.

Last week, while I was interviewing authors at BookExpo America, my latest Shelf Awareness review ran—and it’s a change of pace from my usual science fiction/fantasy fare. Rebecca Makkai’s debut novel, The Borrower, is the sort of story which, had it been published ten years ago, or even five, might have been unironically published as “chick lit.” Or maybe not: Makkai has a three-year consecutive streak of appearing in the Best American Short Stories anthologies, so she could easily be positioned in the same literary matrix in which authors like Curtis Sittenfeld have flourished. As it is, there’s both literary and commercial potential here, which is why I wound up describing The Borrower as “a young woman’s ‘dramedy’ in the vein of early Jennifer Weiner or Marian Keyes.

Early on, there are hints that it might even be an issue-oriented commercial novel à la Jodi Picoult, as Makkai introduces us to Lucy Hull, a twenty-something children’s librarian in a Missouri town who discovers that the parents of one of her regular patrons have enrolled him in a fundamentalist program that promises to cure teenage and pre-adolescent boys of homosexual tendencies. The library is one of the few sources of solace in ten-year-old Ian’s life, especially since Lucy eagerly fuels his love for children’s literature that draws his mother’s scorn for not having “the breath of God in them.” (There is a lot of namechecking of kid’s books along the way, constantly reinforcing Lucy’s coolness—and, by extension, Makkai’s.) The situation escalates when Lucy comes in to work one morning and finds Ian hiding in the library after having run away from home; somehow, this leads to her driving him out of Missouri, first to her parents’ apartment in Chicago and then to various points further east.

But while the issue of Ian’s “escape” never completely fades away, the emphasis shifts towards Lucy’s psychological state. This has its advantages; the more time we dwell on Lucy’s quarterlife crisis, the less time we have to think about the utter implausibility of the “kidnapping” plot, especially the ways in which that trouble never actually catches up with Lucy. (This is particularly unrealistic given that, early in their flight, they run into the guy she’s sort of seeing, who she then proceeds to dump, and he goes back to Missouri and never says a word to anybody about seeing Ian with her.) At the same time, there’s always just enough attention paid to Ian’s dilemma to keep Lucy from coming across as too self-absorbed, and Makkai does a good job of keeping Lucy’s concern about Ian’s emotional well-being from turning into overt Christian-bashing. Or, at least, doing it with self-deprecating humor: “Obliquely comparing his family to the Nazis,” Lucy reflects after one conversation, “was maybe not my finest moment.”

Yes, the well-read young librarian vs. Christian fundamentalist parents setup is a bit too easy, but it’s not as if one comes to that premise expecting a balanced social critique. As an affirmation of liberal, book-loving values, though, Makkai creates what I described in my review as “an entertaining imaginary space.” It’s a bit uneven: Sometimes the literary “playfulness” of things like Lucy’s reframing of her situation in various modes of children’s literature gets in the way of the story; sometimes, as I mentioned earlier, the suspension of disbelief wavers. When it works, though, The Borrower is a strong enough debut that I’m definitely curious to see where Makkai goes next.

1 June 2011 | read this |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.