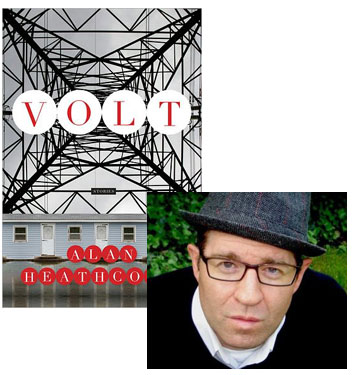

Alan Heathcock, Carried Off “Upon the Sweeping Flood”

The stories in Alan Heathcock‘s debut collection, Volt, are compellingly stark: Unable to deal with the emotions churned up by the accidental death of his son, a man simply wanders off, until he winds up in a new community where he earns money withstanding other people’s physical assaults; a sheriff goes to extraordinary lengths to preserve the tranquility of her community, and then a flood forces her to revisit her actions. The violence in Heathcock’s stories takes on a surreal quality, and yet for all its unworldliness it doesn’t lose its visceral immediacy. In this guest essay, he explains how he’s been inspired by a master of such tales.

I must steel myself. Must be brave. I must not look away. It’s hard and self-conscious and everything in me tells me I’ve gone too far. What will they think of me? What will they think if they know my mind? This is my dilemma, being a writer. I’m a naturally private man, yet the written word eventually becomes very public, judged, interpreted, and for that I try to be brave, to not falter.

I need help. When I am at my weakest I read the work of authors who’ve gone far beyond me, ahead of me, who are revered. In this regard, Joyce Carol Oates is the bravest of writers, one of the fiercest champions of unflinching truth I know.

I own an old ragged paperback of the story collection Upon the Sweeping Flood. The pages are yellow and brittle. On the first page, before any of the stories, is a quote from Oates: “I am concerned with only one thing, the moral and social conditions of my generation.” Just like that. So easy, so focused. My problem is clear. I am distracted, focusing on many things, while her concern is distilled into a single sentence. And oh how she pays out that focus.

The first time I read the title story, I was sitting in a condo on the fifth floor of a building in Chicago, Illinois. I remember it was fall, probably October, and I put the book down, trembling a bit, and stared for a long time into the golden tops of the locust trees outside my window. I was a budding writer then, and remember reflecting on my own work and thinking something like, “You’re not even close. Not even in the ballpark yet.”

13 April 2011 | selling shorts |

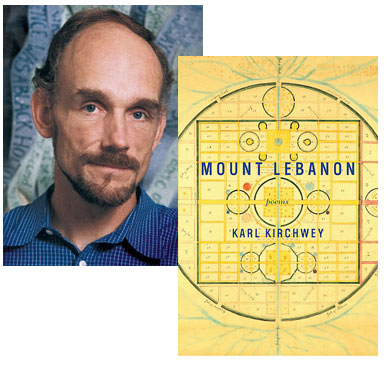

Karl Kirchwey, “Sonnet”

Tell me something I don’t know about love.

The story goes that Paul Verlaine’s mother,

Élisa-Julie-Josèphe-Stephanie Dehée,

kept her miscarried fetuses in a jar.

The poet, returning home drunk one night,

smashed them on the stone dining room floor.Tell me something else.

Casanova once loved a woman who did not love him.

So he collected bits of her hair,

had them made into candies, and ate them secretly.Love must not touch the marrow of the soul.

A poet said that, a long time ago.

Our affections must be breakable chains.

Mount Lebanon is the sixth collection from Karl Kirchwey. It also includes “Propofol” (published in The New Yorker), “Lenox Road” (The New Criterion, as “Three Oaks”), “Wissahickon Schist” (Slate), “The Red Portrait” and “Lemnos” (both in Poetry).

And then there’s “After Three Years” (Little Star), a translation of one of Paul Verlaine’s earliest poems; Kirchwey has translated Verlaine’s debut collection as Poems Under Saturn, also out this month. Here’s Kirchwey on Verlaine: “What appealed to me very powerfully was, first of all, the intense musicality of Verlaine’s lines– impossible to render in English, really, because English is a language of speech stresses, as French is not– and then also the combination of carnality and learning, in the poems. Verlaine was a hot-blooded young man in a repressive society, but he was also, at least intermittently, a spiritual and religious seeker and a scholar on the upward road to Parnassus.”

12 April 2011 | uncategorized |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.