I Hate Watching My Favorite Writers Fight

Early in the research stages of The Stewardess Is Flying the Plane!, I was wrapping up an interview with a director who wanted to hear more about the scope of my project, and I described how I was trying to tackle the entirety of 1970s Hollywood, all the way down to films like… and, honestly, I can’t remember the title right now, but I do remember gleefully describing the photo we’d found of the cut-rate monster costume when the director interrupted me and said something like, “Well, you know, So-and-so put a lot into that movie. A lot of people did.” That comment brought me up short, and, honestly, it’s never been quite as easy for me to be as glibly dismissive of a film or a novel since then.

It’s especially difficult with movies, because film is such a collaborative medium that even if the acting or the script or the direction aren’t up to my standards, the technical people may still be giving it their all—or maybe it’s a case where you can give the actors, writers, or director credit for trying, for putting themselves out there and making a creative statement, even if you think it falls short or you can see where they could have done “better.” Which is pretty much how I’ve come to feel about literature: An author has cared passionately enough about a story to devote himself or herself to writing it, and seeing it through to publication, and I’ve come to recognize that’s not something that we should be casually dismissive about. (Sorry, I know I’m repeating myself.) I’m not saying I’m perfect in this regard, but if something doesn’t work for me artistically, I hope that I’m thoughtful enough to explain why, rather than just shooting it down.

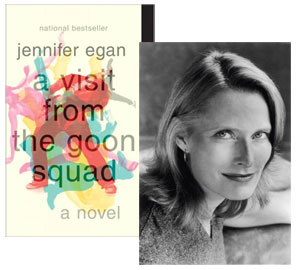

That’s a big part of the perspective from which I’m viewing the backlash against Jennifer Egan’s post-Pulitzer remarks on women novelists and ambition, in the course of which she described “that scandal with the Harvard student who was found to have plagiarized. But she had plagiarized very derivative, banal stuff.” She’s referring to the case of Kaavya Viswanathan, who fell into literary disgrace after it was revealed that her debut novel lifted several chunks from, among other things, Megan McCafferty’s novels—which, like Viswanathan’s other sources, deserve far better than a brushoff as “very derivative, banal stuff.” (McCafferty has said, on Twitter, that she’s received an apology, so there’s that.)

That’s a big part of the perspective from which I’m viewing the backlash against Jennifer Egan’s post-Pulitzer remarks on women novelists and ambition, in the course of which she described “that scandal with the Harvard student who was found to have plagiarized. But she had plagiarized very derivative, banal stuff.” She’s referring to the case of Kaavya Viswanathan, who fell into literary disgrace after it was revealed that her debut novel lifted several chunks from, among other things, Megan McCafferty’s novels—which, like Viswanathan’s other sources, deserve far better than a brushoff as “very derivative, banal stuff.” (McCafferty has said, on Twitter, that she’s received an apology, so there’s that.)

My perspective is also shaped by recognizing that this is part of a long tension between women who self-identify as “literary novelists” and women who self-identify as “chick-lit novelists,” a previous pressure point of which was Egan’s participation in an anthology called This Is Not Chick Lit, which pretty much earned her eternal enmity from some chick-lit novelists, including Jennifer Weiner. Which disappoints me in that way that you’re disappointed when two of your friends just don’t get along with each other and probably never will, and you like them both and you don’t want to take sides and then it becomes sad to hear either of them talking trash about the other. (To further complicate the issue, I actually do know a lot of the writers involved, in a friendly way—though it might be presumptuous of me to claim more than acquaintanceship—so it does feel a bit stronger than a simple literary dispute, but the central issue would remain even if I’d never met any of them.)

None of this has put me off reading A Visit from the Goon Squad; I’ve been a fan of Egan’s for a long time, and I’m eager to finally see what she’s accomplished in this latest novel. (Yes, I’m late to the game, I know.) And I see Megan McCafferty has a new novel, Bumped, coming out next week, so maybe I should take a look at that, and of course Jennifer Weiner has a new book this summer. (And I still need to read the Jodi Picoult that came out last month, now that I think of it…) There’s something else Egan said, just before the cutting remarks, that I wish had taken the spotlight: “My focus is less on the need for women to trumpet their own achievements than to shoot high and achieve a lot.” (Granted, as Sarah Wendell notes, the two are not incompatiable.) We’re fortunate as readers, I think, that a lot of writers (men as well as women, but the issues of exposure and respectability are often more keenly focused on women) are willing to put themselves out there and make the effort. And, as I learned, it’s worth being mindful before we tear any of them down with just a few words.

21 April 2011 | uncategorized |

Civil War Book Club: Adam Goodheart’s 1861

When you get off the train in downtown Richmond, Virginia, you’re just a half-block from the site of that city’s former slave market; reading the plaque that explained this bit of local history, and looking across Main Street at the Slavery Reconciliation Statue, I was forcibly reminded of one of the main reasons I wanted to start the Civil War Book Club—While I may know quite a few things about the Civil War, there’s still much of it I don’t fully understand. The 150th anniversary, which began last week, is a good opportunity to expose myself to this history, and hopefully to share it with others.

I had come to Richmond to meet Adam Goodheart, the author of 1861: The Civil War Awakening, a book that does a fantastic job of exploring how the months after the presidential election of 1860, and the early months of the war, were not a simple matter of “North against South,” but a personal crisis of conscience for every American citizen: Where did our loyalties lie? What did we hold most dear about our nation? Were we willing to fight for it? Adam and I came to Fountain Bookstore to talk about these volatile months for a small but appreciative audience. In the clip above, you’ll hear him read for about fifteen minutes from his account of the last moments in the Confederate assault on the troops stationed at Fort Sumter.

20 April 2011 | civil war 150, interviews |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.