Author2Author: Tom Payne & Zachary Mason

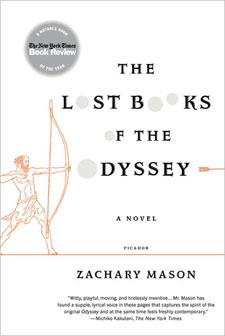

It’s been a long time since we’ve had an Author2Author conversation on Beatrice, but a few months back, when I received paperback copies of Fame: What the Classics Tell Us About Our Cult of Celebrity and The Lost Books of the Odyssey relatively close to one another, I got to thinking that it would be fun to pair Tom Payne and Zachary Mason up and get them talking about our continuing relationship with the classical world, then see where the philosophical trail led them. (After they’d been talking to each other for a bit, I picked up on an idea that had been mentioned about reality television taking inspiration from mythology, and they ran with that, too!)

Zachary Mason: Your book draws parallels between modern celebrities and the Greek Olympians, twelve powerful gods whose spheres of influence cover more or less all of human experience. If there were twelve celebrity Olympians, who would they be, and what would be their spheres of influence?

Zachary Mason: Your book draws parallels between modern celebrities and the Greek Olympians, twelve powerful gods whose spheres of influence cover more or less all of human experience. If there were twelve celebrity Olympians, who would they be, and what would be their spheres of influence?

Tom Payne: I’ve been reading your book with unpardonable stealth, and am greatly admiring it. I’m glad of your question, too, about modern equivalents to the Olympian gods. It’s really tempting to rattle off some answers (although I’ve been mulling this one over for a while now), but maybe I’ll hold back, (a) to maintain some suspense; (b) because who does what Artemis does?—certainly not Miley Cyrus; but mostly (c) because, now that I’ve been reading your book, I’m wondering if something big lies behind it, and I’d like to ask a question of my own.

About The Lost Books of the Odyssey: it’s splendidly unsettling. Your prose has all the calm and magic of myth, so that I’m seduced into the story-telling, so that your inspired deviations from the turns those myths take can startle the reader into thinking, “Hey, that’s not what happened! This would change western civilisation as we know it!” It makes me wonder how things would be if we had different myths.

Which leads me to my question—one I think would exercise us both. What do you think myth is for?

Zachary Mason: In mathematics, there are certain concepts—sets, integers, and prime numbers, for example—that seem somehow essential, and as though they’ve been discovered more than invented. Myth, I think, is analogous, consisting of those stories so essential that they’re compelling even in their most minimal forms. The Odyssey, for instance, retains a certain power even when reduced to a one-paragraph summary, or a few images—a city uselessly besieged for years, a man lost at sea in a hostile fairy archipelago, returning home to find one’s house taken over by hostile men. Myth doesn’t to serve a purpose so much as it is a deep pattern language, something implicit in the kind of minds we have. Oral traditions seem to lend themselves to mythologization, in that they start out (more or less) as stories about particular events, and then, over endless retellings, everything that is inessential is worn away, leaving only the primes of the story.

Tom Payne: I like this idea of primes. It makes me think of Roland Barthes’ work; for example, he takes a story by Balzac and strips it of ornament, figurative language and so on, to see what’s left; and for another example, in Mythologies, he looks at the contemporary world to see how everyday things (all-in wrestling; steak and chips; Garbo’s face; election photography) tell us the kind of stories we feel we need to hear.

I think that the way we look at celebrities sits well with your view of myths that you can reduce to their bare essentials. Any myth that has anything to do with hubris; the Prometheus/Faust myth; the myth that there was ever a golden age; any attempt humans make to re-enact the coming of spring; these would be the ones that seem elemental to the way in which we worship the famous.

What you say about myth makes me all the more intrigued by the way you treat it in The Lost Books… Do you feel sometimes as though you’re reprogramming the myths that feel so permanent to us—in some way unpicking the deep pattern you mention?

Zachary Mason: Celebrity seems to me to be an unusually direct expression of the primate mind. As hierarchical social animals, we want to know what the high status animals are up to, and with mass media there is a much broader consensus about who are the high status humans.

Zachary Mason: Celebrity seems to me to be an unusually direct expression of the primate mind. As hierarchical social animals, we want to know what the high status animals are up to, and with mass media there is a much broader consensus about who are the high status humans.

It’s interesting to look at kinds of people who can be celebrities—for the most part, it seems to be actors, musicians, athletes and politicians (perhaps in that order). Movie actors seem to be more strongly celebrities than television or stage—the explanation may have to do with the vaguely religious impact of sitting in a darkened room watching huge figures move on a glowing screen. Perhaps musicians are on the list because music creates a direct emotional experience, and athletes because of a deeply biologically rooted (and, these days, deeply wrong) belief that physical prowess correlates with

reproductive success. Its also interesting that wealth and power are insufficient for celebrity—the founders of Google, for instance, have immense wealth and a disproportionate hand in shaping the technological future of the world, but it seems unlikely that their personal lives will ever feature in the tabloids—it seems to be necessary to make a broad-spectrum emotional connection.

A primate psychologist once observed a troupe of chimpanzees in which the alpha chimp befriended a beta chimp, groomed and fed him, and helped protect him in exchange for his support in fending off rivals for the troupe leadership; the beta chimp eventually deposed him. In his book, the researcher commented on the alpha chimp’s lack of foresight, thought I think the chimp can hardly be blamed, as his is more or less the plot of, for instance, King Lear, and every fairy tale where the king is overthrown by the captain of the guard.

As for the Lost Books and deep patterns… There was a mathematician who said, “We needer fewer old proofs of new theorems, and more new proofs of old theorems”; perhaps the analogous thing is true of literature. I’m not sure I’d say I was trying to reprogram them, as that I was trying to cut away everything in excess.

Speaking of patterns, perhaps a strong innate meta-pattern is a fascination with variations on a theme, which would explain the reception of novels that are like fugues, and its less important that books and films be realistic than that they are dreams.

Tom Payne: I like this way of anatomising different means of gaining celebrity. The acting one I find especially intriguing, and the image of crowding around their glow in a cinema does remind us of the campfire. There is something magical about acting. They knew it in Shakespeare’s time, when actors were on the dangerous edge of things (they weren’t allowed to have a guild of their own, so weren’t really recognised as contributing to society’s needs). Particularly for Protestants, what actors could produce was too much like an illusion, or a conjuring trick that even its supporters called “bewitching”.

I’m finding it increasingly helpful (however slack this sounds) to conflate actors and politicians. I heard Martin Sheen on the radio recently, on a UK programme called Desert Island Discs, talking about how the Democratic Party approached him to ask if he’d consider running for the Senate. He said that he was flattered, but not qualified. How pleasingly unlike his son this makes him. Hasn’t Charlie Sheen played so many hedonistic parts that he’s come to see it as a way of life? Sheen père went on to say that people confuse celebrity with credibility. It was a nice play on words (I’m just checking now to see if it’s nearly an anagram), but I can’t help thinking that people are celebrities precisely because we do want to believe in them. Juvenal somewhere writes about the very problem that if actors start playing the parts of statesmen, we start to believe that they’re the real thing; which we see with Eastwood and Reagan. I think there’s a bodybuilder who got quite far in Californian state politics, too.

I completely agree about the biological hardwiring that makes us admire athletes. Maybe they make better hunters, and therefore better mates. I did see Raymond Tallis discussing the issue of celebrity once—he’s a biologist who wrote an intriguing book on the head as opposed to the brain—and he didn’t think we are at all hardwired to admire celebrities. To which I say, yeah right. The examples you offer about primate behaviour are more sophisticated than the ones on my radar—I haven’t thought that far back into evolutionary anthropology, really—but Freud considers the same data from apes. There really does seem to be a killing-the-gods pattern among tribes of chimps, who unite against the current champ. I like what you say about this champ’s lack of foresight; it summons up what I see as the whole riddle of celebrity. Why do people want it so much, when it’s so evidently and savagely destructive? Maybe the chimps don’t know about the consequences, but surely we do—there’s the Iliad, after all, for those who missed Gilgamesh the first time around.

Ron’s question about a reality show would be an example of this. There’d be loads of entrants for it, no matter how compromising the show. I’m going to keep thinking about a format, but my problem is that I’d find it hard to improve on a twist, or kink, that cropped up in a series of Celebrity Big Brother in the UK. One of the “celebrities” wasn’t really a celebrity; she was called Chantelle Houghton, and looked a little like Paris Hilton. Her job in the House of Celebrities was to convince them that she, too, was a celebrity—otherwise she’d be evicted. She excelled when housemates were asked to line up in order of importance—several conceded that she had more kleos than the rest of them.

So let’s see. How about The Odyssey? We overrun your house with people out to seduce your wife, and your job is to stop them. (Come to think of it, isn’t the Odyssey the opposite of Joe Millionaire? How much would women like to marry the nebbish who fetches up dressed as a beggar?)

Zachary Mason: I wonder if celebrity is destructive or if it’s just that the kind of people who become celebrities tend to be on the road to destruction in any case. Pursuing a career in the performing arts is, from a certain perspective, insane—only a tiny fraction of aspiring actors become stars, or even able to support themselves by acting—so perhaps the people who try tend to have a tolerance for risk that approaches complete indifference, a characteristic associated with a certain emotional chaos. This pattern could be reinforced by the fact that fear and pain tend to work well on camera. One wonders whether the stars who melt down in public would, had their careers not taken off, have melted down in private in essentially similar but less jet-set ways.

As for reality shows… As Tom chose the Odyssey, I’ll take the Iliad. My show is called “The Achilles Choice.” Every week the remaining contestants must perform some dangerous task, or be eliminated; the tasks will proceed from the ill-advised (driving sixty miles in 35 minutes, say) to the most-likely fatal (swimming sixty meters through a great white shark breeding ground while carrying a raw steak, walking across a tight-rope strung between skyscrapers, stealing a wrist-watch from one of Myanmar’s ruling generals); the rewards will grow at a similar pace (from a lease on a Prius and a new iPad to a Ferrari, a penthouse, and a private jet, and finally a major role in a Hollywood movie). We’d see, in the most direct way, how kleos weighs up against mortality. (Note to reality TV producers: please don’t actually make this show.)

15 April 2011 | author2author |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.