Ellen Elias-Bursac & Albahari’s Amusing Leeches

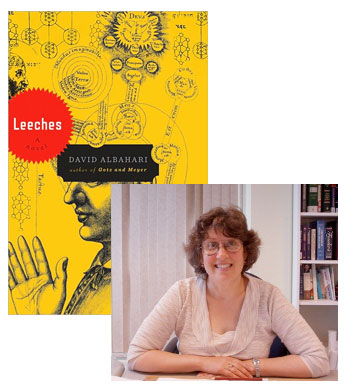

Ellen Elias-Bursaċ has plenty of experience translating the Serbian author David Albahari—her English-language version of his novel Götz and Meyer won the ALTA Translation Award and was tapped for the Barnes & Noble Discover promotion, which is no mean feat for a translated novel, let me assure you. So when a former colleague sent me a copy of Albahari’s latest, Leeches, I thought it would be interesting to hear from Elias-Bursaċ about what attracts her to Albahari’s stories.

Leeches is a thriller, narrated from an undisclosed location outside of Serbia, reprising events that transpired in the spring of 1998 in wartime Belgrade and building to the months just before the NATO bombing campaign. The narrator’s position of exile links it to much of Albahari’s writing during the 1990s, when he was situating his protagonists in Canada (Bait, Snow Man, Globetrotter) and dealing with the war at a continental remove, but, in contrast, the story the narrator tells us in Leeches is situated directly in Belgrade, smack in the middle of the war.

The suspense generated by the thriller format works well to convey the atmosphere of suspended animation in the year before the NATO bombing. Suspended animation is, perhaps, the best way to describe the bated-breath atmosphere the novel creates. In fact the protagonist (never named) and his best friend, Marko, get stoned at frequent intervals throughout the novel. It’s not only their spacy highs and disjointed conversations, but the actual holding of breath in the process of getting high, that typifies for me the feel of the novel. This sense is further enhanced by the format of a single paragraph for the whole novel.

Spacy highs notwithstanding, the novel does not sidestep the reality it addresses. Unlike Götz and Meyer, which refracts questions of wartime responsibility through World War II, Leeches takes on the Miloševiċ regime and the culture it spawned front and center. His protagonist is a Serbian writer who finds himself embroiled in a mysterious, sometimes mystical, chase after an elusive beautiful woman, Margareta, and a mysterious, regenerating manuscript tied in various ways to the Jewish communities of Belgrade and Zemun (a city just across the Danube from Belgrade), and, perhaps, to the protagonist himself. Not so elusive are the neo-Nazi repercussions to his involvement with Jewish themes: attacks on his person, his apartment, the newspaper he works for, that ensue after he begins writing in his regular newspaper column about the plight of Serbian Jews.

The context of the tense, grim story line makes the fact of the humor of Albahari’s writing all the more striking. It’s the humor that motivates me, as a translator, to translate David Albahari’s writing. His protagonists are often rather solemn, first-person characters, usually urban intellectuals, seldom named. While never bumblers, Albahari’s protagonists are often bewildered by what happens to them and their innocence of the obvious brings a dark laughter to the bleakest of situations.

29 April 2011 | in translation |

Read This: Charles Dickens (by Michael Slater)

Last week, I had the opportunity to hear acclaimed Dickens biographer Michael Slater give a late morning lecture about “Dickens’ Shakespeare,” as part of the 92nd Street Y’s “Books and Bagels” series (which used to be known as “Biographers and Brunch”). It was a marvelous talk, in which we learned much about Dickens’ utter disregard for his hero’s biography, preferring to focus on the stories themselves, and frequently Slater would illustrate his theme by reading from Dickens—Nicholas Nickleby and Great Expectations, for example—with a flair for voices that rivalled Sloppy in Our Mutual Friend. (I was assured that the 92Y had recorded the audio from Slater’s talk, and I really hope they put at least one of these segments online.)

Last week, I had the opportunity to hear acclaimed Dickens biographer Michael Slater give a late morning lecture about “Dickens’ Shakespeare,” as part of the 92nd Street Y’s “Books and Bagels” series (which used to be known as “Biographers and Brunch”). It was a marvelous talk, in which we learned much about Dickens’ utter disregard for his hero’s biography, preferring to focus on the stories themselves, and frequently Slater would illustrate his theme by reading from Dickens—Nicholas Nickleby and Great Expectations, for example—with a flair for voices that rivalled Sloppy in Our Mutual Friend. (I was assured that the 92Y had recorded the audio from Slater’s talk, and I really hope they put at least one of these segments online.)

During the Q&A period, Slater described how he had first read Oliver Twist when he was ten years old, “and I was absolutely frightened to death. I didn’t find it funny at all; I found it terrifying.” But he didn’t shy away from reading more, all of which he pursued on his own: “Fortunately, I was never taught Dickens. It just never came up in school.” Even at Oxford, when he declared that he wanted to write a thesis on Dickens, they didn’t quite know what to make of him. What was the subject, somebody in the audience asked? “I’m not sure I can remember now,” he admitted. “The composition…? And reception…? of Charles Dickens’ The Chimes… Sounds gripping, doesn’t it?” (It actually did sound fairly interesting; apparently he went through newspapers from the period looking for the stories that Dickens used as source material for the second of his Christmas books.)

I confess that I haven’t had time to do more than dip into Charles Dickens, which we’ve actually had on our bookshelf for some time; but I did take a look as preparation for Slater’s lecture, and what I read was quite excellent: You could tell Slater knew his stuff, but he wasn’t being ostentatious about it, and he was still able to marshall all this information into the form of a compelling story. More years ago than I care to admit just now, I read Peter Ackroyd’s Dickens, and I loved it, but a lot of information has come to light since then—Slater seems to have more than risen to the challenge, and I may just have to plunk this book into my carry-on bag on my next prolonged vacation, when I’ll have the time to properly devote myself to it.

28 April 2011 | read this |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.