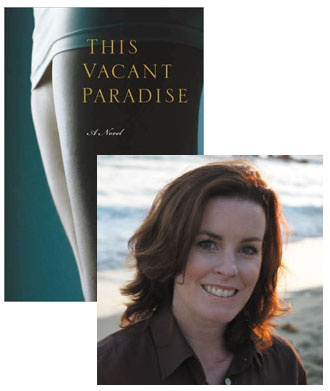

Victoria Patterson & the Continuous Dialogue Between Writers

I was introduced to Victoria Patterson‘s fiction last year, when her short story collection, Drift, was a finalist for The Story Prize, and she was kind enough to write an essay about Frederick Busch for this website. When I heard about her debut novel, This Vacant Paradise, and learned that it started out as a bid at remolding Edith Wharton for contemporary southern California, I was intrigued—and I’m delighted that Victoria was willing to talk about the ways in which great fiction can stay with us and influence the stories we want to tell. I’m looking forward to cracking this novel open this afternoon, and I think after you learn more about it, you’ll want to track it down, too.

As writers, we do tend to talk to each other through our work. John Updike said, “I have almost always begun a book with another book in mind…” Through what he called such “intertextuality,” Updike felt, “writers give each other the courage to carry on.”

More recently, Yiyun Li said of William Trevor, “I talk to him in my stories.” Some of her stories, in fact, are direct responses to Trevor’s stories, reminiscent of Raymond Carver saying he was writing to and for Anton Chekhov.

“It just feels like he’s writing about my own world,” Li explained of Trevor, “or how I feel about the world is the way he feels about the world, and I write about the world the way he does.” Li thanks Trevor in her acknowledgments, and in almost every interview, she mentions him.

While on the surface their worlds are seemingly far apart (Li’s work takes place mostly in China, while Trevor’s work takes place mostly in Ireland), their exacting, careful prose is similar—with a deep sense of loneliness, an underlying melancholy and seriousness, and an understated beauty. Li has conversations with other writers, including arguments—Graham Greene and Iris Murdoch, for instance—but she’s in alignment with Trevor, with whom her connection is deeper. She describes this connection as “intuitive.” Surely, her relationship to Trevor’s work is intimate, and although they’ve met a few times, these interactions “don’t matter…because really it’s the things you write, because you’re talking to a writer, and you really talk through your writing.”

A friend of mine, a fellow student in graduate school for creative writing, used to sleep with headphones, listening to his favorite writers reading their work. This friend hoped the legendary writers would infuse his subconscious, thus emerging miraculously in his own prose during his waking/writing hours.

In Noah Baumbach’s 2005 film The Squid and the Whale, 12-year-old Walt performs Pink Floyd’s “Hey You” at his school’s talent show, claiming to have written it. When confronted on his blatant plagiarism, he asserts—with complete sincerity—that it felt like he’d written it.

John Gardner famously advised writers to copy the great writers word for word in order to learn the craft through the concrete writing of it. Gardner, I believe, was proposing that a writer take the time and effort to absorb a great writer as precisely and directly as possible, with the objective that the writer ultimately find his or her way—through that great writer—to his or her own prose: a close dialogue.

This continuous dialogue between writers past, present, and future gives writing its mysterious electricity, and it comes from close intuitive readings and thoughtful intuitive responses. When the reading and writing become a back and forth—whether it be discussion, argument, homage, or response—things can get exciting.

In 2005, my professor at UC Riverside jokingly called me the Edith Wharton of Orange County—these were the days of the hit TV show, The OC. “You should write a House of Mirth set in Newport Beach,” he told me. Already a Wharton fan, I became consumed by the idea. I studied The House of Mirth, read biographies of Wharton, and her autobiography. I read everything by and about Wharton, reading that was interspersed with Henry James. I lived and breathed Wharton and James for the next four years.

In describing The House of Mirth, Wharton wrote, “The answer was that a frivolous society can acquire dramatic significance only through what its frivolity destroys. It’s tragic implication lies in its power of debasing people and ideals. The answer, in short, was my heroine, Lily Bart.” That, and the determination to portray my characters through the eyes of others, or what Henry James termed the “successive reflectors of consciousness,” became central templates to This Vacant Paradise.

Yet the novel started not as a direct reinterpretation of The House of Mirth, but with an image: I saw my heroine, Esther Wilson, drinking a sour apple martini at a popular restaurant and bar called Shark Island. Sitting at her barstool, feet crossed, Esther came to me. The novel soon strayed from The House of Mirth, and I let it. When I tried to stick too closely to the other story it didn’t work. I wrote a scene that included the Pageant of the Masters in Laguna Beach—a Tableaux Vivant festival custom made to fit the incredible scene in The House of Mirth where Lily impresses everyone with her scandalous beauty, clad in next to nothing. But I cut it because I knew it was trying too hard to be The House of Mirth and had stopped being This Vacant Paradise. A strict definition of a novel limits it, I learned, closing off the writing with a narrow interpretation.

I read Marxist, deconstructionist, and feminist interpretations of The House of Mirth, and these perspectives influenced This Vacant Paradise. I wrote the first chapter through Charlie’s point of view. From a window with one-way visibility, he watches Esther at her barstool, drinking her martini, so that the “male gaze” informs the reader’s first sight. We “see” Esther before we meet her.

I learned everything I could about The House of Mirth and studied Edith Wharton’s life and, at some point, interjected my own personal history, and its connection to hers, into the telling of this story. The story became one that was informed by my own life. I was writing to her, about her, to me, to other women, and more. I took in Edith Wharton and Henry James and what came out was something completely unexpected to me.

And then there are the random influences: Listening to the radio in the car one morning, after dropping my kids off at school, the deejay dished with his cohort about a recent actor who’d divorced his wife, only to marry a younger version. “She looks exactly the same,” he said, “minus twenty years.” Thus Esther’s doppelganger Jennifer Platt twitched into my subconscious, emerging a month or so later on the page.

I didn’t listen to Henry James and Edith Wharton on headphones when I slept, but most likely I was reading them before I closed my eyes, and I beseeched them for help often, hoping for guidance, support, and courage, as I usually end up doing with all the authors that I love, whether they be dead or living.

18 March 2011 | guest authors |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.