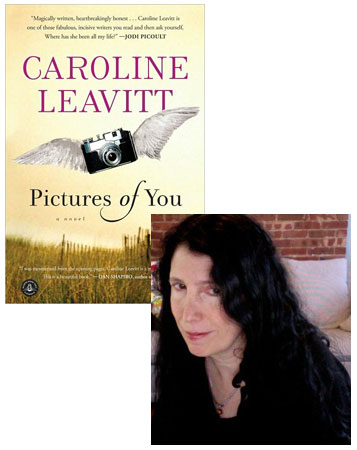

Caroline Leavitt: Literary Can Be Commercial & Vice Versa

I got an email late last year from Leora Skolkin-Smith reminding me that our mutual friend, Caroline Leavitt, had a new novel coming out at the start of 2011. Since then, Pictures of You has been getting a lot of attention, and a reputation as the year’s first breakout “upmarket commercial” novel. (“Upmarket commercial” in this context is marketing language for “a very compelling story told in very polished prose,” and at 150 pages in, I can confirm that characterization.) Caroline and Leora have known each other since they began working together on adapting Leora’s novel, Edges, into a screenplay (now in preproduction with Triboro Films). “We soon began sharing the travails and triumphs of the writing life with our novels,” Leora says, “and then began sharing our personal lives, as well, until now we’re pretty inseparable.” So with Pictures of You arriving in stores, it seemed like a natural fit for Leora to ask Caroline some questions about the novel.

Your blurbs are a truly unusual mix of writers, running the gamut from Robert Olen Butler to Jodi Picoult. Some are intensely “literary”, even “experimental”, and others, talented genre writers. You have a democratic notion of literature and story-telling and you don’t wage an battle against either camp—the “literary” or the “commercial”, a battle that seems to be always flaring up in our writing world far too often (for me anyway). Can you talk a little about your understanding of genre, of fiction and story-telling? And how you see this battle as it wreaks havoc on our collective literary universe?

I hate the notion of genre, because I think it stonewalls the reading experience. Why can’t a literary novel also be a commercial page-turner? Why can’t a commercial romance also be literary? Why do we have to pigeonhole books and writers as if readers aren’t smart enough to discover what a book is offering them just by reading it? I’m hoping the lines between literary and commercial are going to blur more and more. (Case in point: Look at Justin Cronin who wrote a literary and highly commercial vampire novel!) I deliberately wanted to span the gamut of writers for blurbs for Pictures of You—male, female, literary and commercial—simply wanted to underscore that hopefully, a wonderful read is a wonderful read and we really don’t need to always be making value judgments about a book before we’ve even read past the first chapter.

26 January 2011 | interviews |

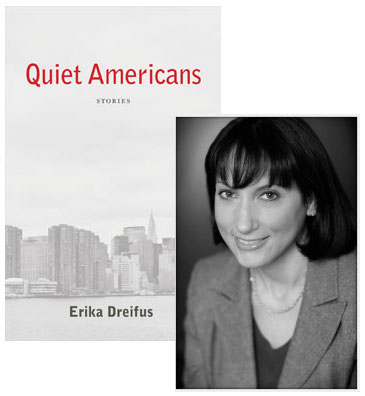

Erika Dreifus & Malamud’s “German Refugee”

I first met Erika Dreifus through her excellent blog Practicing Writing, and when I learned that she was coming out with a collection of short stories, I couldn’t wait to read it. Quiet Americans (which you can buy, signed, direct from the author) is a group of thematically connected stories about German-Jewish families who emigrated to the United States—several of the stories are directly connected, following four generations of the same family from the early 20th century to an attempt to revisit their homeland during the 1972 Olympics. These are powerful stories, with subtle turning points, and they mark a significant literary debut. In this guest essay, Erika explains how one short story, chosen to be among the last century’s finest, resonates with the stories that she has chosen to tell.

I owe my discovery of Bernard Malamud’s “The German Refugee” to The Best American Short Stories of the Century, which joined my bookshelf shortly after its release. And although I don’t normally use the word “frisson” in everyday conversation, it describes exactly what went through me when I saw the title of Malamud’s story in the anthology’s table of contents.

Reading this story as a writer, one notices a number of elements. First, there is the first-person narrator through whose eyes we learn of another character and his conflicts. Perhaps the most famous example of this technique is the Nick Carraway narrative of Jay Gatsby’s story. In “The German Refugee,” American Martin Goldberg recounts the tale of the eponymous “German Refugee,” an older German-Jewish man named Oskar Gassner, whom Martin describes as “the Berlin critic and journalist” who had fled Germany in the months after the Kristallnacht of November 1938. In those days, Martin tells us, he “made a little living” by tutoring such refugees in English, and the meat of the story recalls the summer of 1939, when Martin worked with Gassner in preparation for the latter’s delivery of a lecture in English.

Then, too, for anyone who focuses on language, this story yields rich rewards. For instance, one sees how a character—in this case, a refugee character—gains definition through speech: “‘Zis heat,’ he muttered…. ‘Impozzible. I do not know such heat.’ It was bad enough for me but terrible for him. He had difficulty breathing.” Language itself is almost a minor character in this story, one who inspires tremendous anguish. As Martin reveals: “To many of these people, articulate as they were, the great loss was the loss of language—that they could no longer say what was in them to say. They could, of course, manage to communicate, but just to communicate was frustrating. As Karl Otto Alp, the ex-film star who became a buyer for Macy’s, put it years later, ‘I felt like a child, or worse, often like a moron. I am left with myself unexpressed. What I knew, indeed, what I am becomes to me a burden. My tongue hangs useless.'”

So I have writerly reasons to be interested in this Malamud tale. But undoubtedly it is because of two “German refugees” in my own life that I have revisited this story so often. Like Oskar Gassner, my father’s parents were Jews who emigrated from Germany in the late 1930s. In Oskar’s speech, I can hear theirs.

21 January 2011 | selling shorts |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.