Danica Davidson on Adapting Manga for English Readers

One of the advantages of participating in social networks like Twitter and Facebook is that it puts me in touch with Beatrice readers from lots of different backgrounds, at various stages in their writing careers. I “met” Danica Davidson through Facebook a while back, and when she told me about a recent essay she’d written for another website, which I ended up linking to on the Beatrice Facebook page, we got to talking about something she could do here—I’d known for a while that she had worked in manga, and I’d always been interested in hearing about what it’s like to work on those books, so here we are! (And, by the way, happy birthday to the author!)

Writing is just part of what I do. My main goal is to be a professional novelist (I’ve been interviewed by the Los Angeles Times and featured on the Guide to Literary Agents website about this) and I’ve completed more than one novel. While I work toward this goal, I pay the bills and build my readership as a freelance writer. I’ve written a few hundred articles for more than thirty magazines, newspapers and websites, but the freelance gig that tends to interest people the most would have to be my involvement in the manga translation process.

Manga are Japanese graphic novels and they’ve given me quite a bit of freelance work, as I’ve written about them for such places as Booklist, Comic Book Resources, Graphic Novel Reporter and Publishers Weekly, to name a few. But I’ve also been part of the behind-the-scenes work in the manga world: I’ve written the English adaptation.

It occurred to me that it would be a fun and significant job I could do, so I wrote to manga publishing companies, inquiring. I already knew people from most the companies and they were familiar with my reviews. Digital Manga Publishing, one of the main manga companies in America, gave me a “test,” having me work on some sample pages. I passed and was hired as a freelance adaptor.

29 January 2011 | in translation |

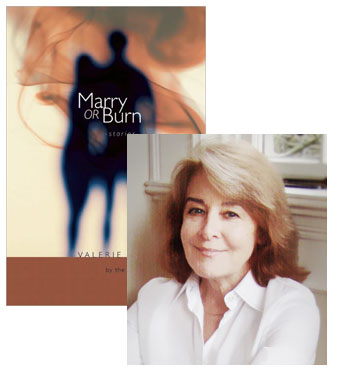

Valerie Trueblood & Welty’s Golden Apples

Valerie Trueblood is an expert at packing a short story with a rich backstory—the opening selections in her new collection, Marry or Burn, span years in their telling, and even stories like “Luck” or “Tom Thumb Wedding” that have a short time span on their surface contain dense pasts that weigh upon the unfolding present. But she doesn’t use the past to explain the present according to some obvious symbolic framework: It’s just that both are filled with incidents that offer implicit insights into her characters. In this essay, Trueblood tells us about another powerful example of the “show, don’t tell” principle of short story writing.

I have several editions of Eudora Welty’s story cycle The Golden Apples, the dearest to me a yellowed paperback, the one with the Bascove cover, small enough to be held open in one hand with the thumb on one half and the little finger on the other. Inside this small book is a world so dense, airy, lilting, lamenting, shocking, calming, and almost crazy with the sheer force of life that I can’t think of another book anything like it. Seven unruly stories are twisted up together, blown full of a sweet hilarity (“Whenever she opened the cabinet, the smell of new sheet music came out swift as an imprisoned spirit, like a pet coon”), and saturated with grief.

I wonder if Wallace Stevens read Welty’s stories. “Description,” he wrote, “is revelation.” I believe it’s in the short story—even more than in the poem—that we see what he meant.

“Why” is the territory of the novel, and the short story doesn’t dawdle there. It has left the path of reason and the outcomes dear to reason, and gone over into the land of the “what.” There, there’s absolutely no end to the things that can be seen to influence each other and to figure in someone’s fate. The short story is the place where these things get their due. My first awareness that they could be lifted into glory by a writer’s certainty that they were glorious came when I read The Golden Apples.

28 January 2011 | selling shorts |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.