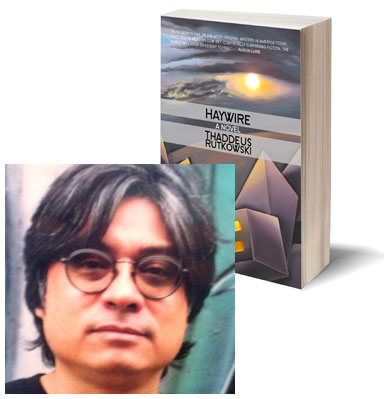

Thaddeus Rutkowski & Brautigan’s Planks of Sugar

Haywire is a series of vignettes narrated by an unnamed figure who, like Thaddeus Rutkowski, is the son of a Polish-American father and a Chinese mother—as you’ll see below, Rutkowski doesn’t hide the autobiographical elements; the protagonist’s first name, though not fully revealed, is even revealed to begin with “T.” But Haywire isn’t a straightforward account of a life, even in fictional form: It presents incidents without explanation or overt retrospective analysis; it skips over large swathes of time; almost nobody in the entire text has a name. And yet the story is still full of resonances and subtle through-lines; in this essay, Rutkowski tells us a bit about another author whose own “flash stories” influenced his style.

In high school, I really enjoyed reading Richard Brautigan’s books. It wasn’t just the content (the hippie lifestyle, the artist/fisherman’s vision) that drew me in, but the way that the author created “novels” out of brief, seemingly unrelated chapters. Some of these chapters contained fewer than 100 words, yet they were complete in themselves. What held them together was a sensibility, an outlook that stayed the same throughout the books.

Re-reading a couple of Brautigan’s books recently, I found the same sense of newness and whimsicality I’d encountered as a teenager. Reading from one “chapter” to the next, I didn’t know what to expect, yet each new passage added to what came before. In the prose book In Watermelon Sugar, for example, the buildings are made of planks of sugar. These planks are pressed at a sort of sawmill, and they come in different colors and varieties (e.g., “soundless sugar”). The planks serve their purpose: They bring a sweetness to the main community, iDeath, and, of course, they hold the buildings up. By repeating the metaphor, Brautigan links disparate scenes in the book.

When I began to write creative pieces myself, I didn’t know how to categorize them. Should I call them fiction or poetry? Those were the two main choices, though my pieces also had a strong autobiographical side. I didn’t consider labels like flash fiction, prose poetry, or mixed genre. (Those headings hadn’t been promoted yet.)

So I saw my pieces as short stories. They contained sentences and paragraphs, as well as characters and dialogue. But I kept everything brief. Much of my work concerns my childhood family, so instead of naming people, I used the words “mother,” “father,” “brother” and “sister.” My narrator was always the first person “I.”

My stories also have settings. In Haywire, the childhood stories take place in Appalachia, where my brother, sister and I were the only foreign-looking kids in school (our mother was Chinese). As the narrative progresses, the setting changes to college campuses, then to a city. The transitions follow my own moves from central Pennsylvania to Ithaca, N.Y., Baltimore, and New York City.

I may be exaggerating when I say that my stories contain plotlines. Some incidents are connected, while others aren’t. For example, the grandmother in Haywire at first lives close to the narrator, then suddenly lives in Florida. The explanation is that a couple of years have passed between the grandmother’s appearances, but the time span isn’t stated. The book covers many years—the narrator’s whole life—so there are gaps. My idea was to bring to light the most interesting, dramatic moments and leave the rest aside.

Another way I organize incidents is to make the endings reflect the beginnings. Here’s a passage from early in Haywire, where the main character, an adolescent boy, is sent to his room by his father to memorize poetry as punishment:

I looked out my window and imagined there was another country on the other side of the nearest mountain. I could climb over the ridge to get to the other realm. Boulders strewn along the summit wouldn’t stop me. On top, I would look over and see a city. I’d walk down the other side and come to a street. The street would take me to a customs office. I’d show my identity papers and cross…

I shut my eyes and mouthed the words. I thought it wouldn’t take long to commit a hundred lines to memory.

At the end of my book, there is a similar passage. It appears as part of a dream sequence, in which the narrator (who now has a family of his own) faces the same sort of dislocation he felt as a child:

On my way up the mountain, I find that the slope is not only steep, it’s vertical. There’s a steel ladder I can hold onto, but even when I’m holding on, I’m afraid of falling. I look for a place to rest, a flat area where I can get off the ladder. But I don’t see any ledges wide enough to stand on. Moving sideways would lead to empty air. So I keep climbing.

I didn’t plan for the image of climbing, of crossing to another place as a way of escape, to appear in both parts of the book, but when I saw the paragraphs placed as they are, I saw a sense in them.

The effect is somewhat like that of the planks of sugar in Brautigan’s book. I don’t know why the planks are made of sugar, but I know there will be meals, conversation, dancing and dying beneath the watermelon shingles.

30 January 2011 | selling shorts |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.