Censoring Past & Present: Nicole Peeler on Teaching Huckleberry Finn

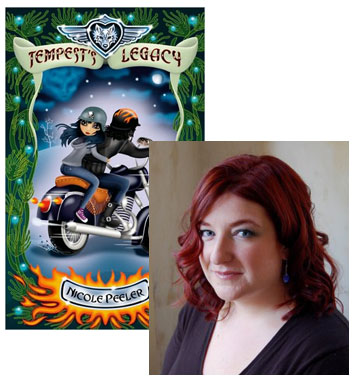

If you’ve been reading Beatrice for a while, you might remember that I named Nicole Peeler‘s debut novel, Tempest Rising, as one of my favorites for 2009—last year, she published a sequel, Tracking the Tempest, and just a few days ago Tempest’s Legacy came out. (I can’t wait to get up to speed!) When she’s not bringing a fresh spin to paranormal romance, Nicole teaches English literature and creative writing as an assistant professor at Seton Hall, and when the controversy broke last week over that bastardized edition of Huckleberry Finn, she had strong reactions, and I invited her to share her thoughts with us.

In the fall of 2008, I began my first teaching job as an assistant professor of English Literature at Louisiana State University in Shreveport. I’d just completed my doctorate in English Literature at the University of Edinburgh, in Scotland, and had lived overseas for over six years. Born near Chicago, I’d done my undergraduate degree in Boston. In other words, I was a thoroughgoing Yankee freshly transplanted to the South, and I was suddenly teaching Americans when I’d only ever taught Europeans. Any culture shock, however, didn’t discourage me, and I jumped into the new job with my usual naive gusto.

And so, when I received the textbook I was to use for a 200-level, non-major’s, “introduction to literature” course, I was thrilled to see one of my very favorite short stories by Flannery O’Conner, “The Artificial Nigger.” I adore this particular work, and immediately added it to my reading list. Only to find myself, about halfway through the semester, staring nervously at my syllabus in front of a roomful of students, about one-third of whom were African-American. For that’s when it dawned on me that I—the Caucasian Yankee, who’d never lived in the South, and hadn’t lived in the US for years—was about to have to say the word “nigger,” in public, a lot. I had to wonder how this would fly.

Luckily, it was about half way through the semester, and I’d come to adore my class. They, in turn, had come to trust me. The roster was large—around thirty-five students—but we managed to make our weekly meet into a giant, anarchical, three-hour discussion in which I was as much referee as professor. Meanwhile, these were mostly “mature” students, our jargon for adults who’d returned to college. Most were pursuing degrees in things like criminal justice, dental hygiene, or accounting. These were not literature majors who’d already struggled through the racist imagery embedded in Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness—although they were about to—or Edith Wharton’s casual anti-Semitism. And yet, to my delight, most of them tucked in to their readings with enthusiasm. I watched my students’ own surprise at their interest in the ideas we dug out, together, from what at first appeared to them as monoliths of text. And yet even I wondered if they’d balk at a story peppered as liberally as a Texan steak with a word we all found reprehensible.

I figured the best way to confront the issue was to do just that: confront it. But I’ll admit: there was a hesitation, and a little bit of a quiver in my throat, when I first had to use my full-on, classroom “stage” voice to say the word, “nigger.” My students, for their part, looked a bit stung. And they looked a bit stung when I had to say it again, and then again, and then again, over the course of the lecture and discussion. In fact, they never stopped looking stung till we moved on to “A Good Man is Hard to Find.” And then they looked stung for an entirely different reason.

But despite the constant pricking that was the word, “nigger,” my students and I had a brilliant discussion. Amongst other things, I write about the pre-ideological formation of values, as you can see in this article about Philip Roth. Basically, that means I look for those places, in literature, where we see how and why people come to believe in what they believe, or how both societies and individuals form their values. So I was careful to contextualize O’Conner’s story not as a work of history, but as a work in which we see the exact moment a young boy becomes a racist. And this is no “historical” racism, but the same kind of racism we deal with today.

To my relief, then my joy, the class loved it. Together, we asked the question that O’Conner’s title poses: What does “artificial nigger” mean? And, together, we discovered O’Conner’s warning that any racial stereotypes “we” use to classify “them” are inevitably artificial. Such artificial constructions serve to create a cage in which not only to place a dangerous Other, but a cage upon which we can then stand and declare our superiority.

I came out of that classroom elated, and I had a similarly uplifting experience teaching that story the next semester. And yet, the following fall when we received our “updated” editions of the same textbook, I was horrified to discover that all traces of “The Artificial Nigger” were gone, replaced by the more decorously titled, “Good Country People.” O’Conner is never comfortable, and my discussions with my subsequent classes were still harrowing. But I missed the particular force of “The Artificial Nigger,” and that story’s singular depiction of how an innocent boy becomes infected by his grandfather’s racist ideologies.

Last week, the blogosphere was alight with discussion of a new edition of Mark Twain’s The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, which censored the word “nigger” and replaced it with “slave.” Given my own experience dealing with recent anthologies, I wasn’t terribly surprised by the editor, Alan Gribben’s, actions, nor was I surprised by the motivations for this removal claimed by both Gribben and his publisher, NewSouth books. The Guardian newspaper reports that NewSouth claims such actions will “counter the ‘pre-emptive censorship’ that Dr. Gribben observes has caused these important works of literature to fall off curriculum lists worldwide.”

In other words, Gribben’s reacting to the fact that editors of anthologies like the one I was formerly using appear to want to “clean up” their tables of contents. Superficially, it might seem like a logical argument—why throw the baby out with the bathwater, or have Huck Finn thrown out just because of the “n-word”? And yet, the media coverage and subsequent backlash from scholars, thinkers, and writers have covered a myriad of reasons why this action is so reprehensible.

A primary argument against removing “nigger” from Huckleberry Finn is that of historical accuracy. Dr. Sarah Churchwell was quoted in The Guardian as saying, “Twain’s books are not just literary documents but historical documents, and that word is totemic because it encodes all of the violence of slavery.” In The New York Times, Francine Prose reflects this “historical accuracy” argument when she writes that the book reminds us that, “we—the United States—were a slave-holding society.” Similarly, Jane Smiley argues that works from our history, “tell us something about the times in which they were created.” While I do not disagree, in any way, that Huckleberry Finn can be used to teach us about our past, I wonder why very few commentators talk about what the novel, as well as the current debate over changing “nigger” to “slave,” says about our present.

New York Times book critic Michiko Kakutani comes close when she writes:

Haven’t we learned by now that removing books from the curriculum just deprives children of exposure to classic works of literature? Worse, it relieves teachers of the fundamental responsibility of putting such books in context—of helping students understand that Huckleberry Finn actually stands as a powerful indictment of slavery (with Nigger Jim its most noble character), of using its contested language as an opportunity to explore the painful complexities of race relations in this country.

Kakutani does raise the idea that the novel’s use of “nigger” is not just about historical race relations, but also about present ones. This idea, however, is mitigated by this paragraph’s closing sentence: “To censor or redact books on school reading lists is a form of denial: shutting the door on harsh historical realities—whitewashing them or pretending they do not exist.” Again, another otherwise supportive thinker relegates Huckleberry Finn to history—making it less a living, breathing text and more of an archeological artifact.

I would argue something sharper, and more painful, which has to do with Gribben’s choice of “slave” to replace “nigger,” and with how critics rely on pointing out the “historical” importance of Huckleberry Finn. Indeed, I would argue that Gribben, in choosing “slave,” does what so much of our media and our popular culture do every day: We act like racism is our history rather than our present. It’s like we’re trying to convince ourselves, as a nation, that the 13th Amendment was a cure-all for both slavery and racism. We know there are “problems,” still. We know the KKK still exists, and we’ve heard all of the statistics stating how African-American communities endure excessive rates of crime, poverty, and disease. But we are no longer a racist country, like we used to be “back then.” Right?

Wrong. While it’s true that many of its most disgusting symptoms, such as lynchings, are far, far less prevalent, racism obviously still exists. Oftentimes, it’s been replaced by other, more palatable and easily disguised incarnations. In high school, I watched white classmates sing along to gangsta rap, or call each other “nigga.” While Kakutani claims such lyrics, when used by the actual rap artists, “reclaim[…] the word from its ugly past,” there was nothing being reclaimed in the halls of my high school, by those resoundingly middle-class Caucasians.

Indeed, as I think about my teaching of “The Artificial Nigger” at LSUS, I have to confront a lot of hard truths. I think I had a hard time saying “nigger” in front of my class because I was afraid I would be misinterpreted. I think I was afraid that my students would assume I was a racist. Because, if I’m honest, I think I’m afraid that I am a racist. I’m afraid that because I grew up in a nation that no longer talks about race, except to roll its eyes and say, “Oh, that’s history,” I don’t spend enough time questioning ideas, stereotypes, actions, and cultural messages that are racist. I tell myself, “Some of my best friends are black,” and then I laugh, mostly out of exasperation, at the impossibility of it all. The fact that I’m proud to have black friends disgusts me, even as I’m proud to have black friends. “Look at me!” I think, “I’m not a racist!” As if I deserve some kind of reward. Then again, considering my grandfather was a member of the KKK, maybe I shouldn’t be so hard on myself.

Which leads me to my final point about such obfuscations of our past and of our present that Gribben’s censoring of Huckleberry Finn represents, and that is of confrontation. We must confront our own assumptions about race, as a nation, or we risk a dangerous complacency. I think this idea best summarized by someone not normally known for his cultural sensitivity: Martin Amis. Amis famously told an audience:

My grandfather was a racist. My father was a bit dodgy. I think I’m pretty free of racism, but I get little impulses, urges and atavisms now and then. […] I can palpably feel that my children are less racist than I am. Their children will be less racist than they are and so it goes on. No one can declare themselves free of prejudice. Our tribal instincts have been with us for five million years, so to snap your fingers and say you have grown out of that is idle. You shouldn’t indulge it in anyone. But it’s delusional to think that we can shrug it off. It is much healthier to look at it that way and not just announce tremblingly that you are completely free of it.

I agree with Amis that race relations across the globe are getting better, and that we—and by we, I mean everyone, not just white Americans—can’t assume we’re not racist simply because we’ve never done anything overtly awful. But I would amend his statement, somewhat. I would argue that it’s much healthier “to look at it,” in general. Indeed, we must always insist on “looking at it,” whether “it” is racism, homophobia, or sexism, no matter how uncomfortable “it” makes us. We must confront our ancestors, and ourselves. We must examine not only our history, but also our present.

Finally, as teachers, we must stand in front of classrooms and talk not only about the history of racism in our country, but its complicated presence in our own time and in our own lives. We must teach those texts, such as Huckleberry Finn and “The Artificial Nigger,” that make our stomachs churn. We must lead the charge in confronting our nation’s demons, and our own, be they past or present. As educators, we must stand in front of our classrooms and say those things that make us nervous, that make us angry, that make us afraid.

Because if we don’t, who will?

11 January 2011 | uncategorized |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.